To Hell And Back in Offenbach's 'Orphée aux enfers Overture'

Since writing about Strauss II last week, I’ve found myself completely pulled into the world of mid-19th century light music. I’m trying to return to Beethoven and the likes, trust me, I really am, I’d love to write about sad Brahms piece sometime in the near future (remember him?), but I cannot turn away from the spectacular weightlessness of light music. Pun intended!! Maybe it’s just the coming of spring — slow, but taking hold of the Midwest now. For example: I was sweating outside last weekend, and that’s the last time I want to listen to a heavy and anxious Bernstein recording of Beethoven’s 5th.

Strauss II also got me back on a whole kick about overtures, so here is perhaps my first beloved orchestra, Jacques Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers Overture, known in English as Orpheus in the Underworld. We all know the Greek myth of Orpheus, but I don’t know, maybe there are teens who read this column who haven’t hit AP Lit yet so they aren’t familiar. Orpheus was a poet and a musician whose wife, Eurydice (a cool name, a much cooler name than any of the Game Of Thrones names people keep naming their babies) dies suddenly of a viper bite on her ankle (actually maybe this is why Eurydice isn’t a popular name) and is sent to the Underworld, as was “the deal” at that time. Orpheus, so overwhelmed in his grief, goes into the Underworld and plays his music for Hades and Persephone, king and queen of the Underworld. And those two say, “okay, great tunes, you can take your wife back with you, but only if you walk out of the Underworld with her behind you and you can’t look back at her until you’re back in the land of the living.” Weird, tricky Underworld conditions, sure, but seems fair enough. Well, you gotta believe that Orpheus messes this up: he gets worried, he looks at Eurydice, she vanishes, this time forever. The Orpheus myth to me was like the purest embodiment of “YOU HAD ONE JOB.” So there’s that.

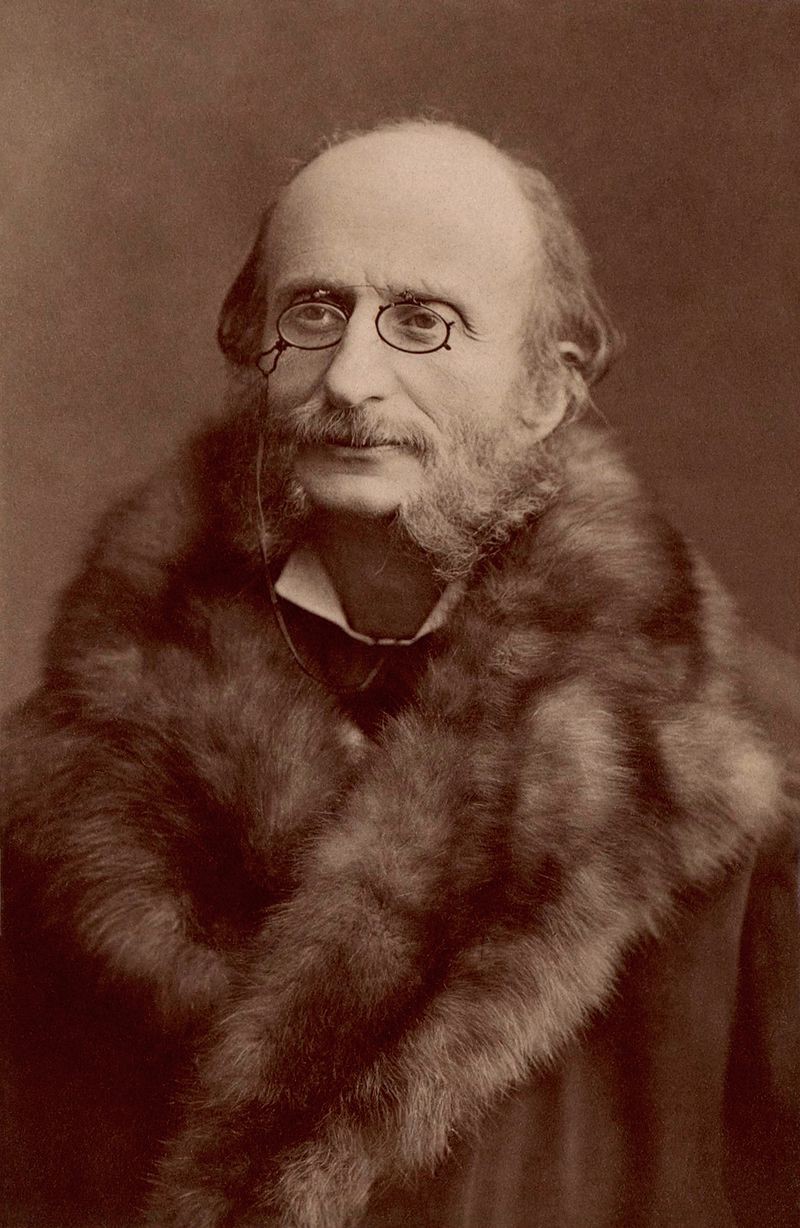

Offenbach, on the other hand, was a German-born French composer who lived from 1819–1880 writing mostly operettas. He looked wild. Look at him.

It was his work that inspired composers like Strauss II, but at the time he was alive, he was kind of the troll of the composing world. Many of his operettas parodied or satirized serious operas or operettas; he was hated by both our friends Berlioz and Wagner (the latter also had something to do with some latent anti-semitism). Was this a good thing for him to do? Honestly, I don’t know. At the time of its premiere in 1858, Orpheus of the Underworld was not an immediate success and in fact panned for being “sacrilegious and disrespectful,” and then, for controversy’s sake, it became a smash success. French people, you know?

The overture (it’s Bernstein, of course) begins with a fairly traditional fanfare, not entirely remarkable, though certain big and brassy enough to catch your attention. This being the overture to an operetta, we do get the movement between themes the way we did with the Die Fledermaus overture. This is like a Broadway overture — a preview of what’s to come. By the time it hits the 22-second mark, with the precious little melody between the high strings and the triangle (the triangle), it should be clear that this is light music unlike you’ve heard before. It’s funny! The tone of it is actively amusing.

The first third of the overture is relatively solo-heavy: we move from the clarinet to the oboe. The oboe solo is strange: melancholy and lyrical all at once. The oboe is not always an easy instrument to love (sorry), because it is tough to be a team player if you play oboe. It doesn’t really sound like anything else! I mean, sure, it sounds kind of like a clarinet, but clarinet at least has the decency to have that rich, expensive-wood-furniture sound to it at times. But there have always been a lot of times to me where the inevitable oboe solo comes in and go, “Oh here’s this idiot.” It’s not fair, I know. This one, however, always catches me. It sounds like such a distinctive voice in the midst of this overture. And then it leads right into the cello, damn it. What could be better? A cello solo? In the first third of a piece? You should be thanking me (and Offenbach).

The piece takes a turn at the 3:51 mark: dark, frightening, intense. This is a formal reset, shifting us out of solo world and back into the triumphant morning announcements of the early moments of this piece. Almost immediately, we’re launched into a violin solo that almost sounds like it would normally come right before the end of a piece of music. This violin solo, however, guides the orchestra along with it through the middle third of the overture. It’s sweet, and it’s perhaps the most traditional “light music” section of the overture. I mean, this is a waltz! It’s a little dance between the violin and the orchestra.

The final third: you know this. You definitely know this because you have been alive on Earth and have ears with which you have heard music for such a long time. It’s the Can-Can. Not just any Can-Can. The Can-Can. This is the Can-Can, from music pop culture and Moulin Rouge! This is the origin. It did not spring forth out of nowhere, but it was, in fact, written by a human man. Isn’t that insane? That someone wrote it? This is its purest form: the drug that is the Can-Can. I have so little to say about it beyond: it is the best thing in the world. You may be a dunce and think that the Can-Can is annoying. It’s fucking not. It is good as hell, and there’s nothing you can do about it. And it’s so perfect, in my humble opinion, that the Overture ends with that. You listen and you think, “this is good, it works, I like it,” in a passive and nice way. It’s a very satisfactory piece, of course, up until that point, but then, when the Can-Can comes in, it’s just BANG. It contextualizes all of it! All of it is a prelude to the Can-Can. And you immediately have to listen to it again, you have to reset, because once you know it’s coming, you know it’s there the whole time, like Orpheus himself, you find yourself looking back.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.