The Big Box Afterlife

Big box stores are the lowest-hanging science fiction prompt in any given town. Big box nostalgia is weak, so thinking about these stores clearly is easier. What, you wonder as you drive by, will happen to the big old Circuit City at Crossroads Plaza or Windermere Village or whatever? The building that used to be a Borders that became a Gap that became a vacant hole? The Walmart on the edge of town that was closed for “plumbing problems?” All those doomed malls, and the big multi-story anchor stores at the end of their long pedestrian halls?

Are people going to live in them? Giant libraries are a nice option. Some old stores have already been turned into large churches; in Florida, I saw an old supermarket that had been turned into a for-profit college. Maybe they could be adapted into enormous low-rent coworking spaces for slightly pre-automation jobs such as “customer support” and “content production.” Maybe they could be turned into extremely weird parks!

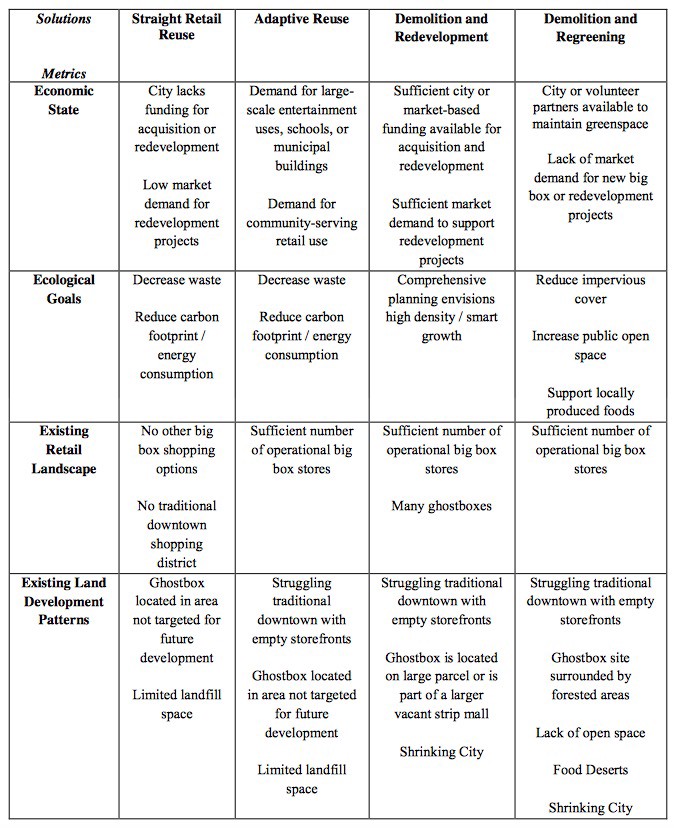

A lot of people are thinking about this more seriously: thousands of large purpose-built structures, many composed mainly of single large rooms with no windows, are not easy to cheaply convert into something else. They are referred to as “ghostboxes” and there are going to be a lot of them. This paper, for example, looks at “legal solutions” (zoning-focused, mainly) to what was, at the time in 2012, understood to be the result of the recent economic downturn.

In 2015, the most visible threat to big box stores is Amazon and its growing group of competitors. Instacart will send people to grocery stores to shop for you; same-day retail delivery services use a mixture of warehouses and stores to courier products to customers’ doors. Meanwhile, Amazon’s ambition has far surpassed merely building the Walmart of the internet. It is attempting to become a marketplace for labor; it is experimenting with drones; it is releasing house-brand products in some of its biggest categories. It is also doing this:

In its ceaseless quest to speed delivery, Amazon.com Inc. wants to turn the U.S. into a nation of couriers.

The Seattle retailer is developing a mobile application that would, in some cases, pay ordinary people, rather than carriers such as United Parcel Service Inc., to drop off packages en route to other destinations, according to people familiar with the matter

Amazon has become increasingly uncomfortable with its reliance on large shipping companies (including the USPS), which are nominally its “partners” but which clearly, in its view, represent a massive cost and inefficiency.

As envisioned, Amazon would enlist brick-and-mortar retailers in urban areas to store the packages, likely renting space from them or paying a per-package fee, the people said. Amazon’s timing for the service, known internally as “On My Way,” couldn’t be learned, and it is possible the company won’t move ahead, the people said.

So: a new plan! Online retailers can rent chunks of current physical retail to start building their own shipping networks. Then, after destroying those retailers, they can turn the buildings into distribution centers. Those warehouses will be supplied on one side by the trucking industry, which is surprisingly close to automation, and accessed on the other by people using their cars to deliver Amazon orders to their neighbors for a few extra freelance dollars. Then, finally, when those cars drive themselves, those old buildings will settle into their role as a nodes in a new retail economy which would be based, much like the one before it, around cars, with the difference that you rarely leave your house except to fetch products that you can somehow afford from the ground-drone or sky-drone waiting in what used to be your driveway. Speaking of which, those big flat Walmart roofs will make great quadcopter pads.

So, problem… solved? Just something to think about next time you’re waiting in line at Dick’s Sporting Goods.

Photo by Rob Stinnett