The Poet Laureate of Fan Fiction

by Adam Carlson

In April, the poet Richard Siken released his second book, War of the Foxes — ten years after Crush, his award-winning debut, which Louise Glück wrote restored “to poetry that sense of crucial moment and crucial utterance which may indeed be the great genius of the form.”

But many fans of the television show Supernatural, which tells the story of the tempestuous relationship between two demon-fighting brothers, thought that Crush was about their favorite characters fucking. The result has been a lot of slash fiction — and other fan works — that appropriate Siken’s poetry, particularly as Tumblr has become the center of fandom, and fandom has become the center of Tumblr. More recently, Siken has become prominent in Sherlock fandom in a similar way: two men, mysteries, fucking. Siken has gotten into it, too, recently creating his own Tumblr and Sherlock slash.

I invited Siken to talk about all of this, and also the new book. We spent the next three weeks trading emails.

Supernatural was the first show whose fan fic I ever discovered. And the timing between that show’s premiere and the release of Crush is something you’ve written about at some length. But do you remember if it was the first fan fic you ever read?

I remember seeing slash here and there, but I suppose the Supernatural community was my first encounter with a group of people building a mythos outside of a show, parallel to a show. I got really interested when they began pulling lines from Crush. And now the Sherlock fandom is pulling lines from Crush (and occasionally War of the Foxes) for their prompts and memes.

Are Supernatural and Sherlock your fandoms? Do you have any?

I’m interested in the fandoms that insist my writing overlaps. I’m also taken by shows like Lost and The X-Files. I followed all the Lost message boards and wikis. I liked the clues and guesses. I like episodic storytelling. I like hypothesizing. For better or worse, television is the great American narrative.

“Insisting your writing overlaps,” that’s interesting. You have a huge following in the Wincest community — those fans who pair Supernatural’s brothers Winchester as lovers, though you’ve said Wincest personally leaves you cold.

It’s not that Wincest leaves me cold, it’s that the idea of participating in it — writing Wincest myself — leaves me cold. There’s an unswayable belief that Crush is already and always has been Wincest. Nothing I say convinces people otherwise, even though Crush was accepted for publication before Supernatural aired. I see the overlap — cars, guns, violence, danger, chasing and escaping, a relationship that seems more than brotherly but not quite romantic — but I think Crush and Supernatural are products of a cultural moment, not products of each other.

I can participate in the Sherlock fandom because there’s room for me. It’s impossible to confuse Sherlock and War of the Foxes. I can write Sherlock fanfic like any other fan and not have it confused with my poems.

Do you regularly find fans who find meaning into your work — really passionately find meaning in a way that helps them articulate specific thoughts and feelings — that you don’t personally hold? Do you find it disconcerting at all, if so?

My 20th-century intention was to make a place where I could articulate my thoughts and feelings. I thought it would be a place where the reader and I could meet. That’s no longer the way storytelling works. Now readers enlarge the places an author has made, include themselves in this larger space, and meet with each other without the author.

At first I found it disconcerting. I think it’s odd that some fans have altered the male/male dynamic of my poems and posted their new, reimagined male/female versions on their blogs. More than odd. It actually makes me uncomfortable. But I’ve sung male/female songs as if they were male/male, so I guess I understand it and do it myself.

I hope readers find meaning in my work. Even if that meaning slides away from my intention. I think, though, there’s a point where revision of my poems — which really is very different — slides too far away from the original text. At that point, I think my work should be considered an influence, if considered at all. I’m not writing to provide others an opportunity to radically translate my inner life into something unrecognizable.

Do you have any thoughts about what your poetry is helping people express, through its repeated use in [fanworks (photosets, prompts, etc.)] — and especially around LGBT desire, especially around essentially subversive desire (reading gay desire into a straight text) — or what lessons your readers may be applying from your work in their own? You mentioned this earlier: the way some fans say the world of Supernatural looks through the lines of Crush.

In the driest language possible, I would say that fan fiction successfully undermines the traditional American heteronormative dynamic in ways that can’t be undone. In wetter language, fan fiction sexualizes. It’s transgressive because it suggests the possibility of the erotic. It’s political, because it complicates power structures. And it’s personal, because it grants permission for range of previously unacceptable expressions and interactions. I think my poems enact a space for complicated, multivalent relationships. I think that’s the draw.

And yet, the Wincest and Johnlock fandoms put their attention to very different kinds of interactions. In Wincest fanfic the relationship is aggressive and incestuous, forged in life-or-death battles with angels and demons. The brothers are young, handsome, similar, fated to be together, and on the run. In Johnlock fan fic, the relationship is tender and between friends. They are older and dissimilar. They don’t share a common history. They are not fated to be together. Instead, they choose each other.

Here’s the biggest question and the biggest problem: What are the consequences of sexualizing these relationships? The possibility of erotic desire may or may not be hinted at in the original work — but ignore that. The probability of romantic love could be low or high — but ignore that. The suggestion that these partnerships are necessarily monogamous, supersede all other potential loves or lovers, and could be considered a type of marriage — ignore that. The question, the problem: How can I possibly convince anyone that I could like my best friend for non-sexual reasons? How do I make room for the possibility of deep care and tenderness between men who aren’t fucking if I sexualize every male/male relationship I encounter? Perhaps the subtleties come later. Perhaps we need to push all the way into highly erotic realms to allow ourselves the room to pull back into places of possible non-sexual tenderness.

Could you talk a bit more about your participation in the Sherlock fandom? You’re writing fic for it — are you also a reader? Do you look through other fanworks? Is there someone out there on AO3 unknowingly getting feedback on their fics from you?

Some of the stories are astoundingly great — worth reading twice, three times — but I don’t give specific feedback.

Why Sherlock: Does anything in that series speak to you as a fan, urge you to write fan fiction?

They invited me. Well, I figured they invited me when they started using #sikenlock. I read somewhere that “Siken ships harder than the entire fandom,” so I decided to ship intentionally.

Have you ever thought about the parallel, or do you think it’s fair to say a parallel exists, between what War of the Foxes is talking about (art, representation, ekphrasis; the limits and challenges thereof) and what fan fiction, less explicitly, is also confronting?

Wow. That’s a great question. I just looked up the definition of parallel, so I can get it right. The concerns of War of the Foxes and fan fiction are concurrent, coexistent, and aligned, but they are not similar. They are opposite gestures. Fan fiction is concerned with an original work and the community that interacts with it, adds to it. War of the Foxes is concerned with the personal relationship between a singular painter and his specific paintings. The paintings referred to in Foxes are my own, or are imagined, so even the ekphrasis is contained within the world of the work.

I like that: “concurrent, coexistent, and aligned.” I think it captures the simultaneous attention both gestures, though opposite, often pay to the process of creation from the perspective of the piece of art being created. I want to circle back a bit. What’s the last piece of fan fiction that moved you — a piece, in your words, worth reading two or three times?

Mention one writer and a dozen others feel slighted. In the Sherlock fandom, I like the pieces that show Sherlock’s weird mix of sexuality and logic. And his investigations of the mix.

Completely far afield from our conversation, but it’s just occurred to me: Soup recurs in your poetry — as a thing to be thankful for; as a nourishing thing. I’m not a huge soup fan, so maybe that’s it. But are you?

Soup is one of my favorites. Also a great image, great metaphor. Into the soup. The soup of it. The soup isn’t ready yet. The bowl of it. A spoon of it.

“The soup of it” — I’ve never heard that! Use it in a sentence?

In elementary school, I saw a film strip about the origins of life. It was suggested that lightning hit the ocean — the primordial soup — and started things happening. It was not very believable, but I like the idea that everything starts with soup and lightning.

Do you remember when you became aware of the following your poetry had on the Internet? Was it around the premiere of Supernatural, or a few years later? And a corollary: If the following began to coalesce back in the mid aughts, do you remember where? Or was Tumblr the first network to give it blossom?

Quotes on blogs first. Pics posted of tattoos of my lines. Then wallpapers, GIFs, and original art with text from Crush showed up when I Googled my name. Then poems as responses to my poems, as imitations of my poems, sprung from prompts based on my poems. Then Supernatural and the move to Tumblr, and then Sikenlock. And somewhere in there there’s also I Can Haz Siken: the Tumblr “devoted to the kitten work of American poet Richard Siken,” where the lines pulled from poems are translated into lolcat language.

The story is, allegedly, that a woman inside the Supernatural fandom was trying to convince people that Siken poems could exist outside the fandom. And further, and perhaps worse, that Siken quotes could be put over any set of images and still resonate with meaning. So she made a Tumblr to prove her point.

I want to explore an earlier point you raised, about this twenty-first-century notion of readers enlarging a work to make space enough for themselves away from the author, in an adjacent idea. Speaking specifically of how your poetry is often reblogged/republished online: I see it spread as epigraphs or a tagline or as the framing articulation or prompt of some fanwork. To many, your body of work may entirely consist of pieces of poetry affixed to pieces of other things. Which seems to me like a very cool and bizarre thing!, a radical recontext. Does the fact that your poetry is so often diced up, and to many readers is so diceable, play a role in how you think about it, either when writing or simply regarding?

I’m conflicted. Seriously and significantly conflicted. Confucius is famous for his aphorisms; Oscar Wilde — infamous for his whip-smart quips. But they were working in the realm of that unit: the quote. I’m not working in that unit. It’s a matter of scale and venue. To be quotable (or diceable, or modular, or granular) was not my goal. It’s hard to be upset about it, but it was not my goal.

A good line is a good line. A good line well placed is an experience. That was the goal: an experience, a larger unit, enough space to move, to hold propulsions, to let the intentionally unsaid things shimmer in the highly charged spaces between the lines. I crafted poems — units made out of lines placed in a specific order — and the poems have disappeared. My loveseats have been broken into chairs, into matchsticks.

So how do we respect an original work while we aggregate around it? I was speaking with a friend the other night, and she said her favorite line of mine was “I couldn’t get the boy to kill me, but I wore his sweater for the longest time.” But that’s not the line. I wrote the word jacket, not sweater. A very different connotation — and connotation is important in poetry — because jacket can be considered as a thicker skin (among other things) in a way that sweater cannot. She was being sloppy, but still — words matter or they don’t. If they matter, don’t change them. If they don’t, then why bother praising the line?

Each modification dilutes. Each distortion cheapens the work, cripples it, erases it. Whether it’s done in sloppiness, or out of a desire to claim and internalize the work, or with intentional malice, it still amounts to a falsification. We have to be careful, when we build around an existing work, that we don’t ruin it.

So the reverse! As your work accumulates in, say, the Sherlock community, do you have any thought about (and this is mawkish) a “Siken effect” in that same space?

Every author’s blindspot. I’ll never understand the effect of my writing on anyone or in any venue. I’d love to hear — or overhear — what people think, but I doubt I will. I doubt anyone really knows. I don’t think I’d ever be able to articulate how I’ve been affected by others. And I’m not sure I’d tell them if I did. But I’d love to know. It’s curiosity, certainly. It’s vanity, probably. I think every stone dreams about the kind of ripples it could make when it hits the lake. But the truth could be disheartening, or even paralyzing. Perhaps it’s better not to know.

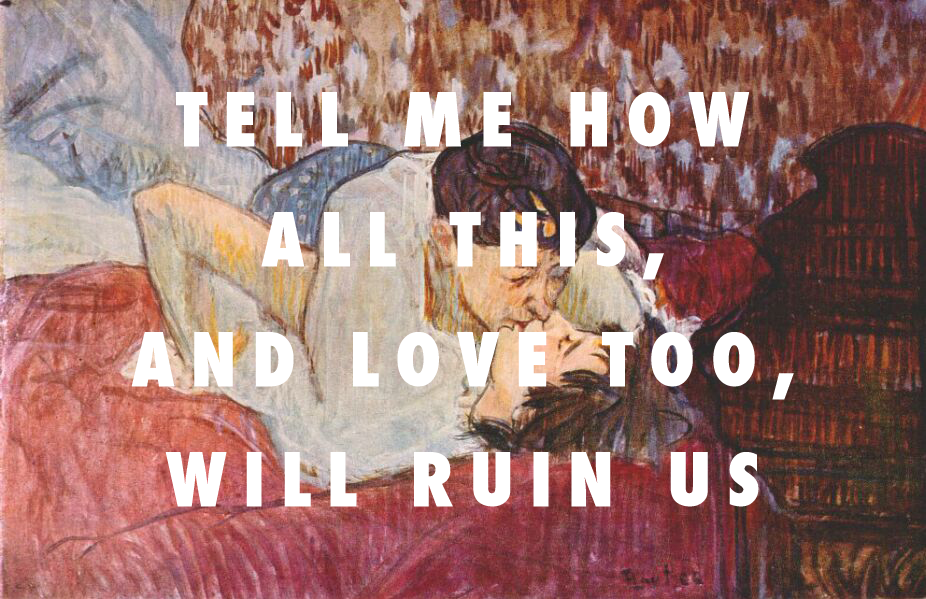

Image of Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Kiss and Richard Siken’s “Scheherazade” by Siken and Art