Good Kill, Easy War

by Emily Greenhouse

A drone strike comes fast, but the prelude is long: it stalks, it looms. Last fall, Steve Coll reported from Pakistan on the terror that civilians face as drones circle above them, sometimes for days. “People below looked up to watch the machines,” he wrote, “hovering at about twenty thousand feet, capable of unleashing fire at any moment, like dragon’s breath.” Good Kill, a new film by the writer and director Andrew Niccol, focusses on the people on the other end: the watchers, who bathe in the grimy imagery of the screen, always poised to deliver death from on high.

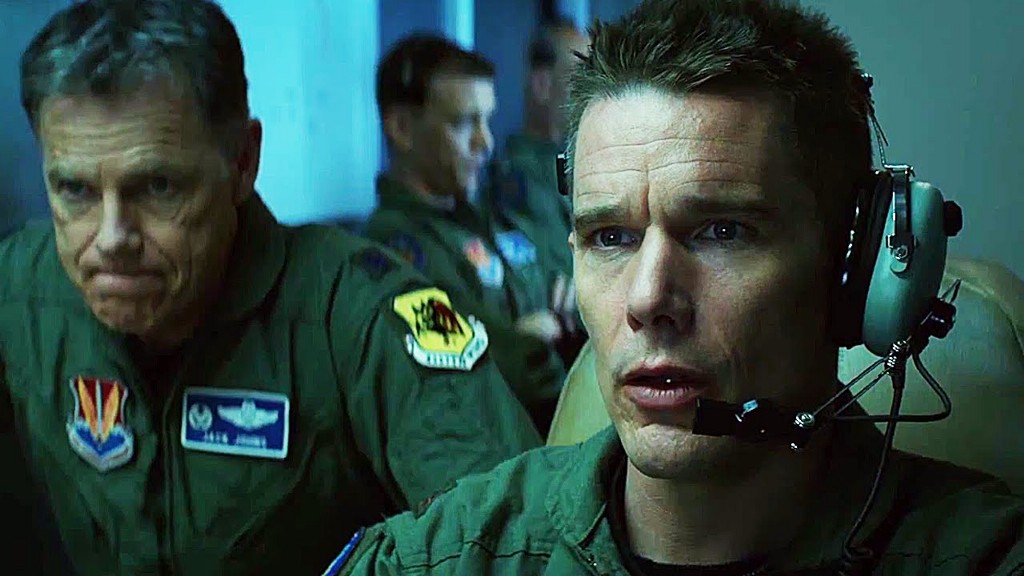

Ethan Hawke plays Tommy Egan, a U.S. Air Force Major who, after three thousand hours as the pilot of an F-16, is back stateside in Nevada, which means he can leave the base in Las Vegas every night to return home and spend time with the wife and kids. But this job, this life, isn’t what he signed up for. The film is a story, not subtly told, of stark moral disconnection, of a man longing for the honor and blustery courage of a Hemingway hero. Egan sits with other pilots in a metal trailer, operating drones. We watch as he watches as his target comes into focus. “Splash,” Egan, the unerring pilot, says. Then comes the explosion: “Good kill.”

Niccol makes movies about the intersection between technology and ethics — stories, as Hawke put it to me, “where technology pushes to a place where we’re on unsure ground ethically.” They do not tend toward understatement. But what they might lack in finesse, they can make up for in prescience and concern. The Truman Show, which he wrote and co-produced, presaged both the rise of reality TV and the near-ceaseless documentation and performance of our lives with tiny cameras that follow us everywhere, while Gattaca, the first project Niccol and Hawke worked on together, was released in 1997, and its vision of a future society carved by eugenics only feels more eerily prophetic as time goes on.

Good Kill, however, isn’t science fiction or a what-if. It’s a war movie that takes place, roughly speaking, in the present, during the escalation of the American drone war, and it asks a moral question of war waged by joystick: How much integrity is there to combat, as Hawke put it, “if you’re killing people but you’re not actually putting your own life at risk?” His unhappy character’s concern seems to be, at times, what becomes of the American hero of the battlefield when there is no battle, just a field of pixels? For Egan, Hawke said, “It’s not really about the war being good or bad, it’s about his own integrity. He’s feeling like a coward. This is a guy who I think dreamed of being a pilot. He’s grieving the death of his dream.”

Good Kill seems to be Niccol’s attempt to report out the answers to some of these questions. Hawke told me that when Niccol sent him the Good Kill script, “I realized how little I understood about the drone program. I didn’t have the criteria, the information, to have an educated opinion.” Niccol deliberately set the film in 2010 because it’s the last year that details of the drone program were open to journalists. “A lot of the words in the movie are not mine,” Niccol told the Hollywood Reporter. “They’re directly from the head of the CIA.” So the drama of Good Kill, according to Hawke, is simply our reality. “Technology makes the messy work of life easier to avoid,” he told me. “My generation is the first generation that’s been really asked to do this” — wage war by day, do dishes, watch Hulu, drink beer and play with dogs by night and by weekend. “I’ve met a few drone pilots, guys who work a whole shift flying a drone remotely with a joystick, who go home, buy potato chips and play video games all night long.”

Hawke seemed matter-of-fact in his approach to drones — he declined to comment on the specifics of President Obama’s drone program. As he put it to me, “Being against drones is kind of like being against the Internet — it’s the future.” He told me that he appreciated that Niccol’s thinking “doesn’t come from a left-wing or right-wing point of view, but a humanitarian point of view,” and that he is “always very suspect of art that claims to have a political agenda. I think if you just try to tell the truth from a character-based point of view, that truth will be political. I’ve never had an agenda with the audience about how people think. I’m kind of allergic to films that try to get your vote.”

Good Kill may not be quite partisan, but it is decidedly didactic. Niccol’s sensitivity and moral charge are clear, and the torment in Hawke’s performance is the most affecting and nuanced thing about Good Kill. But the other characters in the pilot’s hut feel like expository stand-ins. Nowhere is this more evident than in the onscreen depiction of women. It’s no surprise when the sole woman in Egan’s unit, Vera (Zoë Kravitz), gets the sexy outfits and the moral outrage (“Since when did we become Hamas… they give Nobel Peace Prizes for this now?’), plus some other contrived lines. Egan’s wife, Molly (January Jones), a former dancer, gets the usual alone together lines, as Egan, depressed, tunes out and hits the bottle. When a sullen Molly tells her husband, “to cheat on someone you have to be in a relationship,” she may as well be talking to Don Draper.

Even if indelicate, Good Kill comes at a moment, after Zero Dark Thirty and American Sniper, when American entertainment is looking at wars that resemble Call of Duty, not night-time raids. This past season on Homeland, we watched Carrie Mathison with her eyes on the drone feed. We saw her asset — her lover, even her ally — look up, and realize what will come. Frank Underwood on the latest season of House of Cards reckoned with the legal and moral matter of drone strikes — and of how much to tell the American public. And next Sunday at the Public Theater, Anne Hathaway will close her performance as a drone pilot, in “Grounded,” by George Brant. Some of her lines there mirror Egan’s: “I will see my daughter grow up. I will kiss my husband good night every night.” And, “the threat of death has been removed.” She takes her daughter to the mall and can’t escape the eye of the surveillance camera. “There’s always a camera, right? J. C. Penney or Afghanistan. Everything is witnessed.”

Hawke, in advance of the publicity rounds, clearly meditated on violence. Philosophizing a little on drones, Hawke mentioned Ayn Rand. He mentioned Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. He said, “The only two things that ever stopped wars is body bags coming home — the expense of the thing — or conquering a nation.” Today is a different time. “Here the cost is relatively cheap, but you’re never going to conquer, you’re not even there. It creates a state of perpetual war.” That seems to be the story Hawke wanted to tell. “War and cinema have had a long history and the only way the public have a real knowledge is through storytelling,” he said.

Good Kill, as a final product, is a maybe little too obvious. But when we’re dealing with something as murky, as obscured, as the American “War on Terror,” maybe obvious is what’s called for.