Uber Dreams

Last week was Earth Day, which you could’ve celebrated by “finding the right clean energy solutions for your household,” as the Incredible Hulk enjoined everyone, or by eating a local agricultural product instead of produce grown with “Californian oil,” or making some earth-friendly Tumblr image macros, or you could have…taken a ride in an UberPool.

Uber’s Pool car service “matches two riders — with up to one friend each — heading in the same direction.” This is advertised most straightforwardly as a way to save money by splitting the cost of a ride with another person, while not giving up “Uber-style on-demand convenience and reliability: just push the button like before and get a car in five minutes.” But for Earth Day, Uber presented using UberPool as a “pledge” that could be taken to get “a car off the road, and cut emissions,” because the act of sharing an Uber with someone else inherently means one fewer Uber driver is ferrying a single person to a destination, and because, over the long term, it will help Uber reduce car ownership altogether.

The idea that being ferried in a car by a private driver helps the environment or somehow reduces the number of cars on the road may seem disingenuous at best, especially in a city like New York, where Uber offered, “in honor of Earth Day,” five-dollar flat rates to use Pool in Manhattan, but it is perfectly logical if you begin from the assumption that the only way those two riders could have gotten where they were going was in an Uber, or at least in a car. This, of course, is exactly where this idea springs from; as such, it is wholly earnest. So is the also seemingly incongruous idea that Uber, whose independently contracted labor force is largely composed of people who own cars — some of whom recently purchased brand new ones at Uber’s behest and with its guidance — wants to end car ownership. But it’s an idea that Uber has grown more insistent on vocalizing since it first introduced Pool last summer, and since its valuation has ballooned by orders of magnitude to north of forty billion dollars, necessitating that its implicit goals of total global transit disruption become accordingly explicit (cf. “that experience of like, ‘I am living in the future. I pushed a button and a car rolled up and now I’m a frickin’ pimp,’” to “Since day one, Uber has been committed to changing people’s lives by revolutionizing urban transportation”). In the blog post that announced Pool at the end of last summer, a single sentence notes, “At these price points, Uber really is cost-competitive with owning a car, which is a game-changer for consumers.” Last week, in an update on UberPool, “It’s a Beautiful (Pool) Day in the Neighborhood,” written by Conor Myhrvold, a data analyst for Uber who is the son of former Microsoft CTO and current third-most-famous molecular gastronomist in the world, Nathan Myhrvold, Uber’s vision to eliminate car ownership was the core of the post:

[O]ur vision is to help solve some of the most pressing problems cities around the globe are facing. Congestion is projected to get much worse over the next decade, and it’s barely tolerable now in many cities. The only real solution is to reduce the number of cars on the road.

Our carpooling service, uberPOOL, is helping to make that vision of fewer cars a reality. With uberPOOL you share the ride — and the cost — with another person who happens to be requesting a ride along a similar route. Riders can save up to 50% while adding only a few minutes of time per trip. With the lower prices, people can move past car ownership, as taking Uber becomes less expensive than using and maintaining a personal vehicle. And that impact on congestion can be powerful.

Making car ownership “a thing of the past” is a convenient mission statement — it is utopic, transformative, and vaguely humanitarian — not least because it both elides that most of Uber’s non-employee labor force is composed of people who own cars and acknowledges and welcomes their eventual obsolescence, which Uber is actively working toward.

@danprimack fair enough… driverless in 2030 FTW… 🙂 /@MikeIsaac

— travis kalanick (@travisk) February 7, 2015

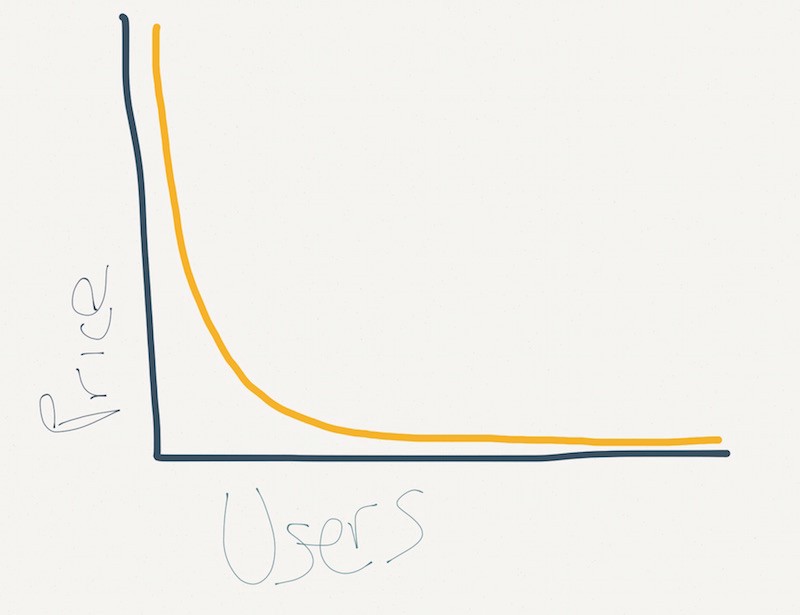

But getting to that point — which, in Uber’s vision, anytime that anybody wants to go anywhere, an app embedded somewhere on their body will signal Uber’s ubiquitous, perfectly optimized network of electric-powered self-driving conveyances that a piece of cargo is ready for transport, because it is so cheap and efficient that locomoting any other way would be unthinkable — requires enormous scale, even before it can replace human drivers. It needs a lot of people in a lot of places taking a lot of Ubers, and it needs its prices to come as close to free as possible — both to advance the longer term goal of eliminating car ownership, and to satisfy its more immediate need for more users. Because it always need more users.

In many cities, UberX is already substantially cheaper than traditional taxis, a feat Uber has accomplished in part by reducing the cost its greatest expense — drivers — through rate cuts that it promises are balanced out by increases in demand. But in light of driver protests, spurred in part by fare cuts, it’s difficult to see how it could drive these costs down much further in order to continue to lower its base rates. Even so, the fare reductions achieved through UberX have been sufficient to require enough users that on most weekends in New York and other major cities, Uber finds itself in the peculiar position of being forced to effectively turn away users through surge pricing precisely when its customers most want to use the service because it cannot meet demand. But UberPool conveniently solves, or at least ameliorates, both of those problems: By putting two riders in one car, it allows Uber to essentially halve users’ base rates without degrading driver wages any further, and it allows Uber to more effectively meet demand without either putting more drivers on the road or turning away riders through increased fares. By lowering rates, it increases the potential base of users, and by expanding capacity, it maximizes the number of users that Uber can service at any given time. Little wonder Uber is pushing Pool aggressively with various five-dollar fare promotions to normalize its usage, even if it doesn’t actually reduce congestion. (If the number of new users that Uber entices through Pool’s pricing sufficiently outpaces the number of cars it “pulls off the road,” it doesn’t: Using Uber’s logic that every UberPool rider equals one car off the road, suppose that Uber already has a hundred customers, and it entices all of them to switch to Pool, cutting the number of cars on the road to fifty. If Pool’s low rates brings in more than a hundred new users because they can finally afford Uber, there will be additional cars on the road But maybe it won’t! It’s reasonable to assume Uber will show us the data in a blog post.)

For the next couple of weekends, UberPool rides between Brooklyn and Manhattan that follow the L line will be just five dollars. This is not for Earth Day, but is part of what is becoming an Uber tradition of ribbing public transit during occasional downtime through promotional fares. (Previously, Uber offered “free transfers” when the G train, which connects Williamsburg, Greenpoint (“north Williamsburg”), and Long Island City (“Condo City”) was out of service. Strangely, Uber has never offered reduced or free rides during service disruptions in Far Rockaway or the Bronx, hmm.) In San Francisco, Lyft recently announced “HotSpots,” dedicated, common pickup points for Lyft Lines (its version of UberPool), at which fares cost just three dollars. You may recognize these as “bus stops.” There is probably something amusing in that Uber and Lyft have independently arrived at services designed to transport large numbers of people which resemble, in some ways, the mass transit systems they are designed to d i s r u p t (though, in their efforts to be perfectly optimal, are inherently neither redistributive nor progressive like actual public transit tends to be — and they likely never will be, without regulation). It turns out that mass transit is extremely efficient at moving around large quantities people and even, in some cases, getting them to “move past car ownership” en masse. What Uber and Lyft are building toward, in other words, is best understood as a privatized mass transit system built on top of public roads.

No company is better than Uber at telling so many seemingly dissonant stories at once: It is creating jobs, which it will obsolete; it is good for the environment because it will end car ownership, except that it puts people in automobiles instead of buses or trains; it is making transit cheaper, until, perhaps, it is the only form of transportation; and it is inevitable, after it unilaterally remakes or outright replaces city infrastructure. And all of those stories are, in one way or another, probably true.