Graceland Deferred

by Tyler Gillespie

At a stoplight in Memphis, seven hours after leaving New Orleans, my roommate and I idled next to a nineties-style, three-windowed white limousine with Elvis Presley’s profile outlined on its side door. The King’s face pointed toward a small, blue wall lined with silver block letters that spelled out Elvis Presley Boulevard, the street’s official name since 1971. On the corner stood a visitor’s center, which looked more like a bowling alley than any type of official state building. The boulevard stretched on in the distance, parallel lines of fast food joints and car dealerships, until we saw the Heartbreak Hotel. After the Presley-faced limo sped into away, we drove by the singer’s former home, which was closed for the evening. But we weren’t disappointed: The next morning, we were going to Graceland.

In the late eighties, Paul Simon sang, “I’m going to Graceland / For reasons I cannot explain.” He’s not the only one. Each year, nearly six hundred thousand Elvis fans buy tickets to tour the grounds where the King is buried. The property, a 13.8-acre estate, with a twenty-three room mansion, racquetball court, a car museum, and an archives studio, was purchased in 1957 for reportedly just over a hundred thousand dollars. Twenty years later, at the age of forty-two, Presley died there; his then-fiancee Ginger Alden found him unconscious on the bathroom floor. After his death, relatives, like his aunt, moved into Graceland, and five years later, his ex-wife Priscilla opened it up for public tours. In 1993, his daughter, Lisa Marie, inherited the property, which is now a designated National Historic Landmark.

A day at Graceland can cost almost as much as one at Disney World. Tours start at thirty-six dollars and run as high as seventy-seven. Each package comes with a self-guided iPad tour narrated by Full House’s own rocker-uncle John Stamos. After my roommate and I discussed our options, we landed on the forty-five-dollar platinum tour package, which included access to Presley’s airplane collection and an “Archive Experience,” basically a presentation of rare artifacts from the vaults, given by an actual human. The mid-price package sadly meant we’d forgo “front-of-the-line mansion access,” but we wanted to save money for souvenirs.

On a recent first date, a guy told me he owned an Elvis cookbook. “Elvis loved pie,” he said. “The book contained some of his favorite recipes.” While there was no follow-up date, his Presley fandom lead me to some of the weirder fan merchandise. An Ebay search for “Elvis” returned nearly two hundred thousand hits: a commemorative pocket knife, a G.I. Blues Christmas teddy bear set, and Sun Studio collector’s plates galore. Presley is printed on money, stamps, patches, magazines, and photo albums. His image is on items ranging from beach towels to a Monopoly board to a homemade-looking piece of “clay art” selling for eighty dollars. When I told my mom about my Graceland plans, she asked me to buy her Elvis-themed salt-and-pepper shakers. I hoped to find them at “Graceland Crossing,” a Presley shopping center we passed before we turned into the parking lot of our hotel, the Days Inn at Graceland.

Lit up by a neon guitar near the entrance, the hotel’s lobby was a shrine to Presley mania: Mock-gold records lined the walls, while a statue, mouth open, mid-song, stood next to a wood table cluttered by framed photos of him. A giant portrait, the most handsome image in the lobby, hung behind the counter to greet visitors, while a white bust kept the front desk worker company. I paid for our sixty-five-dollar room and walked by a poster board covered in purple flowers to commemorate Presley’s recent eightieth birthday. From our balcony, I could see the guitar-shaped pool in the courtyard, and what I am pretty sure was one of Presley’s old planes, permanently grounded next to the Heartbreak Hotel. By the pool was a mural of Las Vegas, where Presley played residences, wed Priscilla, and now marries couples for about two hundred dollars.

Before I crawled into bed, I studied the room’s photos of Presley at different phases of his life. In Presley canon, his career changes are often placed in four shorthand categories: the early “Hound Dog” years; the movie years (he made thirty-one films); the concert years (signaled by the 1968 television broadcast of Elvis, widely known asthe ’68 Comeback Special because it marked Presley’s return from a ten-year performing hiatus); and the “Viva Las Vegas” jumpsuit years. In one of my room’s photos, he wears a uniform to commemorate his years of service in the army. In another, he’s decked out in a white jump suit, grabbing a microphone stand. Next to it was a photo of him lounging in a Hawaiian shirt; this Elvis watched over me as I drifted off to sleep.

I had wanted to find an Elvis impersonator — who greatly prefer being called “Elvis Tribute Artists” — but a hotel worker told us we’d come during the “off season.” There are an estimated eighty-five thousand ETAs around the world, but apparently, none live in Memphis full-time. During “the season,” she said, which coincides with Elvis Week, a ten-day celebration in mid-August, flyers for ETA performances clutter the hotel lobby’s windows as competitive ETAs flock to the city to compete in the “Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest” to win twenty thousand dollars, a contract to perform with Legends in Concert, and the distinction of being the “best representation of the legacy of Elvis Presley.” To qualify, an impersonator must win a preliminary round held at one of nineteen earlier competitions sanctioned by Elvis Presley Enterprises — an organization created by “The Elvis Presley Trust” to handle official Presley and Graceland business — which take place in cities like Presley’s birthplace of Tupelo, Mississippi, Ontario, Canada and Lancashire, England.

With so many ETAs out there, only a select few can make a living off of the craft. In 2012, thirty-year-old Victor Trevino, Jr., placed second in the big competition, which scores contenders based on their vocals (forty percent), style (twenty percent), stagewear (twenty percent) and presence (twenty percent). In a YouTube clip from that year’s performance, Trevino walks on stage to screaming fans, wearing a fifteen-hundred-dollar gold jacket. Before he starts singing “It’s Now or Never,” he smirks, perfectly mimicking Presley’s half-lip curl. When he sings, his voice hits a similar treble and vibrato that matches the King’s later vocal stylings; if you close your eyes, you almost forget how young Trevino is. As a full-time tribute artist since 2007, he’s performed internationally in countries such as Sweden and Spain, where he did a week-run of a show that portrays Presley’s different eras. “They really like the shows in foreign countries,” he told me. “He never really got to do any full-blown concerts in foreign countries.” On Gigmasters.com, a booking site for impersonators, his rates now range from two hundred and fifty to twenty-five hundred dollars per hour.

When Trevino was in college, someone suggested he start performing as Elvis. He eventually competed in a Legends concert in Branson, Missouri, where he was scouted by managers who booked him for Elvis Lives, a touring show formatted as a “musical journey” of Presley’s career from the earliest Sun Studios years to the ’68 Comeback Special. The iconic black leather suit of the Comeback Special is most comfortable for Trevino to portray, because of his youthful look. He told me that a respectful tribute artist knows how to have an authentic characteron stage; he also doesn’t “particularly like” the way he looks in a jumpsuit, Presley’s iconic later-career uniform. “There’s some people who constantly think they’re Elvis,” he said. “It’s the weirdest thing. I don’t care for those kind of people.”

Along with Elvis Lives and Legends, Trevino also occasionally stars in a show called “A Night to Remember,” which pays homage to the Million Dollar Quartet, a 1956 Presley jam session which included Johnny Cash. The impromptu set was recorded by Jack Clement, who, Trevino says, asked him to record original music when they performed together in Europe. While he never followed up with Clement, who died in 2013, Trevino still works on some of his own music. Mostly though, he wants to honor the King’s legacy. “Elvis wasn’t the first rock ’n’ roller, but he was the most important,” he said. “His music not only changed America, it changed the world.”

The day after arriving in Memphis, I woke up early to hit the continental breakfast. As I made my way to the free eggs and waffles, I noticed small ice patches. “How charming,” I thought, “there’s a little bit of snow on the ground.” At the breakfast nook, I grabbed coffee and sat at a table with fifteen other Elvis early-birds, older people who wore mostly white t-shirts and talked quietly amongst themselves. Their eyes slowly began gravitating toward the TV. A newscaster was announcing that schools and businesses would shut down for the winter weather. “They’d never close Graceland,” I thought. “That’d be just so wrong and un-American.”

One of the other breakfast eaters, who sat beside a cardboard cut-out of a young Presley, called Graceland. Then, she delivered the bad news. It had shut down for the day. “We came all the way from Winnipeg,” a woman at a nearby table said. We had started breakfast as strangers, but now we bonded through our grief. In Februarys, the mansion is closed on Tuesdays, and the weatherman predicted worse weather for Wednesday. “Graceland may be closed for weeks,” one of my fellow breakfast mourners said. “We may never get to see it.”

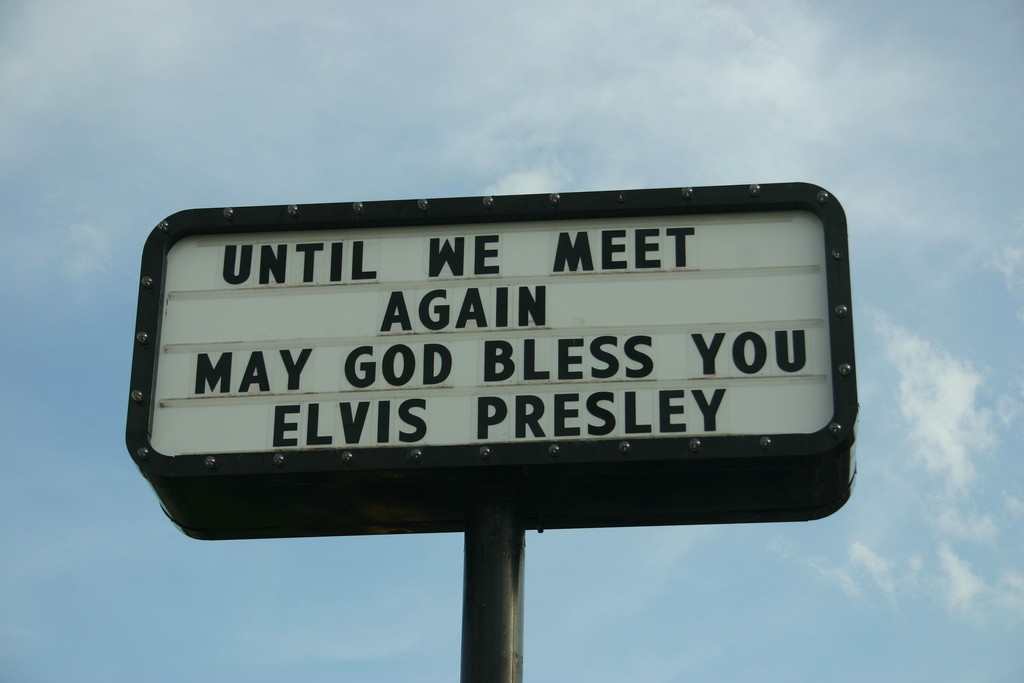

My roommate and I took the next hour or two to process our feelings. We’d be denied entrance into the famous, music-note iron gates. We wouldn’t step foot onto his racquet ball court. We couldn’t walk among his hall of gold records.We’d miss out on the airplane tour and the automobile museum and all his archives. No jumpsuits. Dejected, we decided to cancel the rest of our trip. We didn’t have the time or money to wait out the winter storm, so, only one day after we arrived in Memphis, we scraped ice from the car’s windshield and prepared for the drive back to New Orleans. After I stepped over some ice, I looked up at the Days Inn road sign which read: Until We Meet Again May God Bless You, Elvis Presley.“At the very least we can have some retail therapy at a souvenir shop,” I said as we drove away from the hotel. “I want to buy it all.” There are probably ten Elvis-themed shops on Elvis Boulevard, but they were all closed, too.

Three days later, in New Orleans, after I recounted my failed Graceland endeavors, a friend mentioned the Krewe of the Rolling Elvi, a group of men who dress up as Elvis and ride scooters in a Mardi Gras parade. I’d seen them roll the previous year and remembered their sparkly jumpsuits, Elvis wigs, and sunglasses. They had ridden glowing bikes through a line of outstretched hands. This year, the Krewe counted a hundred and nineteen “rolling members” and thirty-five “Memphis Mafia,” guys who were basically auditioning for full-fledged membership in the Krewe. There were also twenty-five Priscillas, a “lady’s auxiliary” who wore big buns to resemble the King’s ex-wife. Graceland may be the epicenter of the Presley universe, but his fans live everywhere.

On the Friday after Mardis Gras, I walked to a crawfish boil to meet the thirty-one-year-old Krewe captain Tim Clements. While he chatted with some people, I noticed how he looked strikingly like the sixties, Elvis is Back!-album Presley. Though his Gmail icon had shown him in full Presley gear, I hadn’t expected such as strong resemblance — he could pass as the King’s distant cousin, except that he speaks with an unmistakably New Orleans who dat drawl. “When you see a group of Elvi riding their scooters,” he said, between bites of the season’s first crawfish batch, “it’s the coolest thing in the world.”

As a kid, Clement’s sister listened to New Kids on the Block, but he played Presley songs like “Return to Sender” and “Teddy Bear.” In 2007, he first witnessed the Rolling Elvi — a term, he says, is the grammatically correct plural of “Elvis” — a sighting which proved monumental. “It was the greatest frickin’ thing I’d ever seen in my life,” he said. “If there’s anything I love more than Elvis, it’s Mardis Gras, so the Krewe was made for me.” But it wasn’t easy for him to join the organization; they wouldn’t return his emails. One day, he noticed a guy wearing a Rolling Elvi shirt, and the guy told him about an annual Presley death-day party that many Krewe members attend. Clements dressed in a jumpsuit and hopped on his Vespa to hit up the party. He hounded the Krewe until they let him in, mostly, he says, because he naturally had “the sideburns” to go with the costume.

Before he joined in 2009, the Krewe mostly met on Presley’s birthday and death-day parties. In costume, they all introduced themselves as Elvis, so they didn’t really know each other. He decided to organize different functions and at these events, he says, he’d see members for the first time “without their sunglasses or hair.” As the organization grew, charities asked members to perform at events. Eight or ten guys, he says, now make regular appearances. There’s even a section of the Krewe called “The Jailhouse Rockers,” which works on their dance steps for these functions.

But Mardis Gras remains the biggest event of the season. They ride in the massive Krewe of Muses parade, which features over one thousand riding members and the all-female Muses. In 2011, Clements, dressed in full-on Presley gear, and re-created his wedding proposal during the parade. He had a blinking ring for a throw (items members toss from floats), and he gave his wife one “to put next to her real ring.” It was also the first year, he says, his scooter did not break down during the ride.

Before I left the boil, Clements told me to check out Clockwork Elvis, fronted by a man he considers the “hands-down best” Presley singer in New Orleans. The band happened to be playing a gig at a bar within walking distance of my house, so a few hours later, I went and listened to Clockwork Elvis’s funkified rendition of “Hound Dog.” The voice was as good as Clements said; it sounded like an updated version of Presley, confident and raspy, yet somehow still melodic. Multi-colored Christmas lights hung from the ceiling to help light the stage as the band played Presley songs in alphabetical order (their choice to organize the night’s set). About twenty people, a few more than who’d earlier mourned with me when Graceland closed, convened with the King’s spirit at the eccentric neighborhood bar. A gray-haired man in a button-up shirt bobbed his head in a corner booth. A college couple drank Coronas while a tipsy woman, feeling the music, shakily danced.

Clockwork Elvis formed back in 2001 at the suggestion of a bar owner who wanted an Elvis band to play at his parties. While the band had kind of started as a joke, they realized they had fun playing together, and, after a few solid shows, people asked them to perform at different functions, like an all-expenses-paid trip to play at a wedding in Hawaii. (The couple, however, separated less than two weeks before their nuptials.) After a few years of being called “The Elvis Band,” they changed to their current name to avoid becoming “just be another tribute band.” The band decided to juxtapose Presley with Alex DeLarge from Clockwork Orange to show how both were “fictional characters” in their own right; their lead singer DC Harbold now regularly wears a Clockwork hat.

During the band’s set break, Harbold smoked a cigarette at the bar. I told him I’d just come from Memphis, but I couldn’t bring myself to mention that we didn’t make it into Graceland. When most people think of Presley, they imagine rhinestones, over the top costumes, sideburns, rambling, and scarf-throwing. But Harbold, who manages No Fun, a comic book store, by day, wears jeans and a short-sleeve shirt. At times, he sings with a cigarette loosely hanging from his lips. The exaggeration of impersonators, he says, has more to do with the iconography of American pop culture than the musician. “We’ve lionized Elvis and canonized him to the point of being a twentieth century American Jesus,” he said. “Elvis was a real person who grew up just like the rest of us, but had a talent and was in the right place at the right time.”

Harbold says that Presley’s legacy is music that’s “young, dangerous, sexual, and unexpected,” but people expect the over-affectation of Elvis. He thinks that it’s a “mockery” for people to just associate Presley with wardrobe. “He liked dressing up and liked cool suits,” he said, “but the bulk of his career had nothing to do with jumpsuits.” Still, he admits that the get-ups are more fun to wear, because “guys love wearing onesies, man.”

While Clockwork Elvis played a country-meets-soul version of “G.I. Blues,” my favorite song from the movie of the same name, I realized I was glad my trip to Graceland didn’t work out: I wouldn’t have heard this if I had made it to the mansion. Though he died thirty-seven years ago, Presley’s fans keep him alive. As Harbold belted out the “G.I. Blue’s” lyric, “We’d like to be heroes, but all we do here is march,” I thought about Presley’s small-town, Mississippi roots. He could have never dreamed people would portray him for a living — his legacy is some type of great, hallucinatory American Dream, and it seems like we won’t be waking up from it anytime soon.

Photos by Betsy Weber, Mark Stephenson, Kees Wielemaker, and Dudley B. Batchelor, Jr., via Flickr Creative Commons