Did You Eat The Bones?

by Stuart Ross

Food marketing is psychotic. It creeps. Smithsonian magazine ran a cover story with the headline How the Chicken Conquered the World. “Let us now praise chicken in all its extra-crispy glory! Chicken, the mascot of globalization, the universal symbol of middlebrow culinary aspiration!” That was last year. “Nothing is more worthless than an individual chicken,” Joy Williams once observed. Not for Smithsonian. Obviously there was some war going on and the chickens kicked our ass.

It’s not just the birds. For a character in Francesco Pacifico’s novel The Story of my Purity, the place of psychosis is apricot pastries: “Industrial apricots had become humanity’s enemy number one, what the end of the world smells like.”

Apricots and Chickens 1, Humanity 0.

A few years ago the insanity became too much. I wanted to relearn the language of food. I waged a personal war against the conquering chicken.

Learning how to be a vegetarian is indeed similar to learning a new language. You must practice every day. You will comically misunderstand. You will say stupid things. You will mix up how to use your tenses. You will never truly “get it.” The dominant culture, fluent in eating chicken, will always have the last laugh.

It’s not easy, and no one very much cares.

You care. Because you have touched a new consciousness. And you’ve accepted there is something to food consciousness other than what you have known since you knew what it even meant to know. You’ve become a human being who dreams of a human being incapable of shedding blood. Your new passions, like Borges’ Judas scholar, both justify and wreck your life. You find yourself fucked by new ideas. This engorging submission to the idea of being penetrated by radically new concepts seems like one reason vegetarians are broadly perceived as faggots. We’re all about fundamentals, and it’s a short trip to the fundament.

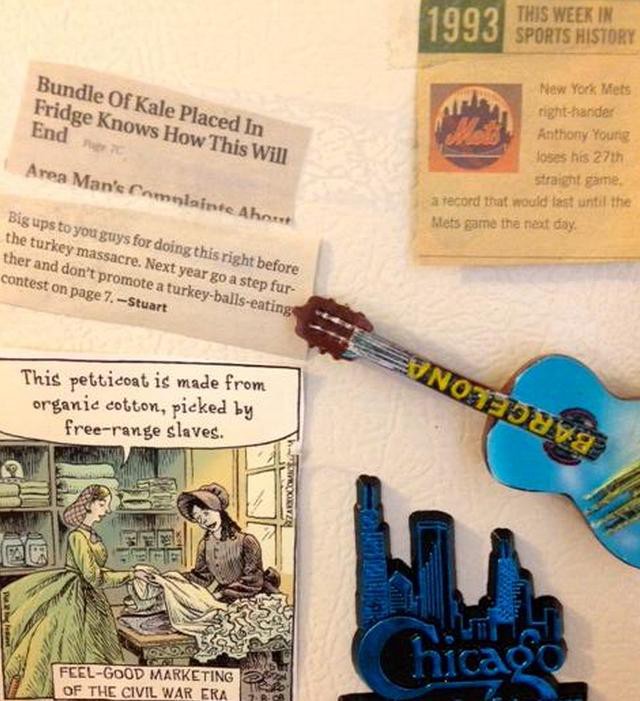

Sometimes a fundament is a testicle. A few years ago it struck me as very peculiar that my alt-weekly’s “Vegetarian Issue” mentioned a turkey-balls-eating contest on page 7. This was around “Thanksgiving” time. I left a witty comment on their blog about it. The next week they printed my blog comment. I cut it out and put it on our fridge.

The neck of the Barcelona guitar in the photo below points to the comment.

Even though it enraged me that a turkey-balls-eating contest got press in the Vegetarian Issue, what really upset me was the realization that the turkey testicle had conquered my alt-weekly. The hipper part of my town doesn’t see a problem with eating a bird’s balls. Or, more than that, with proclaiming that there will be the eating of a bird’s balls, it’ll be judged, and y’all should come.

* * *

In fact I maintain a spreadsheet of every animal referenced in in my alt-weekly. These are animals that, according to my interpretation of the copy, might still be alive at press time. Here’s an incomplete bulleted list from a recent week’s issue:

Page 4: Five pigs, five chefs, five winemakers, probably armed with more than five glasses of wine.

Page 8: The slaughterhouse specializes in veal, lamb, and goat. Just like in the old days, the animals come from farms across the midwest. The facility processes 2,500 animals per week…. [Since] animal blood is definitely not halal… it takes USDA inspectors four hours to clean up the blood after every kill. (Not that more irony is needed but the subheading of this story is “Evidence of Life in These Times.”)

Page 25: Chefs challenging chefs with an ingredient of their choice. [This week’s] key ingredient: Live Frogs.

Most of us wouldn’t know the best way to kill a chicken if it asked us to. Most of us don’t realize that the best way to slaughter a rabbit is with a swift smack with the back of a hand. What we do know is our marketing, the marketing of food and in particular the marketing of meat. We kill it every time. For example, something like this tweet, which suggests pure selflessness can be achieved by letting someone you love eat your chicken. And a bright B2C social marketer at the corporation thought eating this chicken’s bones deserved the kicker of a hashtag.

Nothing says “I love you” more than letting someone else have your last piece of chicken. #iatethebones instagram.com/p/YVwvmFNwiw/

— KFC Colonel (@kfc_colonel) April 20, 2013

So that’s what says I love you. Is a chicken, like a diamond, forever? Not only is this in a language I claim to understand in a different way, this is also in a language I cannot claim to understand. If Joy Williams is right, and nothing is more worthless than one chicken (and she suggested this in 1997; since then, a chicken’s worthlessness has only increased) why does this tweet make a chicken seem so valuable? It’s just a chicken. Google it and it’s usually 23 million being killed each day in America. How does one in 23 million say I love you?

That is one lottery-winning chicken.

I hesitate to use the numbers. I don’t want to show my chicken-eating buddies slaughterhouse photos. Besides, we all live in the city. The killing floor doesn’t really come near us. The only time I see a live chicken is when I’m wasted and fast-forwarding through Rocky II. I’d bet good money that the writer of the above tweet lives in a city, or at the very least she’s typing from a suburban office park. She’s not brainstorming this seductive copy from the conference rooms of gambrel-roofed barns, the rooster’s crow her inspiration.

We’re too good at this. And we seem to love it. Just as the meat solutions plants have gotten so good at the killing, the big bad wolves of the big bad city have gotten so good at the marketing, so batty with the seduction. Stephen Eisenman, in his study of art and Abu-Ghraib, defines this subtle marketing skill, cribbed from the classical art, as follows:

represent your victims as if they were taking pleasure, or at least accepting the rationality of their own annihilation … as laughing cows and dancing pigs decorate signs outside butcher shops and BBQ joints.

Being seduced by this deleterious logic is what the small towns and the big towns share as a single-origin. When we market our meat as well as we do, we are the leopards in the temple, and we are all bit players in the sacrificial shtick, every “this hurts me more than it hurts you” farce, whether we do it from our barns or from our skyscrapers.

* * *

Once I saw the laughing pig and I laughingly licked my ribs. I didn’t always see another language in meat. Like most Americans I knew only one language, Standard American English, and it’s from this I knew the language of chicken. Now I know the chicken has been profiled. I don’t understand how eating the chicken says I love you, and it makes me dizzy with regret.

The general consciousness has been raised in my lifetime. Talk to older vegetarians and they’ll kvetch about how much easier it is for you young pacifists to come out of the closet these days. It shows, too, because so many of us are looking for a new grammar for food. We need an entirely new language to make us buy different things. I’d even settle for a new verb tense. Present heightened awareness.

In one of his cheerier observations, the novelist Michel Houellebecq suggests that nature is a repulsive cesspit, and it may be humankind’s role on earth to commandeer the only solution: the final holocaust against nature. I guess? Sounds like bad “Star Trek.” I don’t want to think so. We think it used to be better back then. Maybe it was. In Measure for Measure, probably first performed the day after Christmas in the year 1604, the flirty nun Isabella pleads with the Spitzerish horndog Angelo for the life of the man Angelo has sent to death. She begs for mercy in this strain:

He is not prepared for death. Even in our kitchens we kill the fowl in season. Shall we serve heaven with less respect than we do minister to our gross selves?

It would appear that in 2013, we shall. We are being kinda gross when we brag we ate the bones. We no longer kill only the fowl in season, we just fowl and fowl and fowl, for all seasons. The chicken has conquered our world. We eat the king’s bones with glee. Mouths full, there are no words left.

* * *

Our grandfathers never talked back to their food. They didn’t look good food in the mouth. Mine was a butcher, from the Bronx, borough of butchers. He was my king. For him, steak was clock. Fowl was work. He sliced off bits of fingernail throughout the day, the scent of shed blood hounding him. The only marketing he ever saw were the bubble letters announcing the cut and cents per pound. His freezer at home was filled with wholesale steaks and chops, and tubs of Key Food-brand orange sherbet. Steak and sherbet, that’s all he ate. He didn’t need the potatoes, the asparagus. He liked his steak bloody, never tartare.

He woke up at 3:30 a.m., came home at 3:30 p.m., reclined in his chair, finished the crosswords in the Post, the News and the Times, Mondays thru Sundays. When the crossword was finished he dropped the whole paper to the carpet. That’s when I would crawl over and snatch it away, devour the sour news and snark I couldn’t begin to understand. I’d look up, take a peek at the spine of the book he would’ve started reading, doorstops about the tragedies at Treblinka and Nagasaki. And what today might be brokered as WWII fan fiction. What I wouldn’t give for an audit trail of his library borrowings.

I remember the first day I brought home The Village Voice, the alt-weekly of my tweens. I was dying to impress him with it.

“Maybe this has a puzzle for you,” I said.

“Don’t bother with all that jazz,” he said.

That was his catchphrase dismissal, especially to me. I’d object. I wanted all that jazz. He’d be happy to argue it out with me, as long as he got to talk the entire time and he ended up being right.

He passed away during the era of Jazz Pepsi, which also failed quickly, which also failed quietly.

When I’m placing a food order I think of him. Mealtimes are when we remember our dead. I can hear him mocking me when I order a radical Reuben piled high with slices of seitan, dressed with thousand island vegenaise. The other morning I was in Dunkin’ Donuts, wondering what I could get, and I couldn’t stop staring at the Wake-Up Wrap® . Look at it, I seethed to myself, just look at it. How could anything with turkey sausage wake anyone up? What is wrong with this comatose country, what is wrong with Dunkin Donuts’, what is wrong with this particular Dunkin Donuts’, this is my Dunkin’ Donuts, why doesn’t it rebel?

Why do you care about all that jazz? I could hear the old man’s voice. Just order your whole wheat bagel. Then you can get to work.

Stuart Ross is a writer living in Chicago. He blogs here and twitters here. Photo by Mugley.