An Internet Tabloid In The Time Of Comets And Mass Suicide

On the night after the Heaven’s Gate UFO cultists were discovered dead by mass suicide in a San Diego suburban McMansion, I was standing in a dark patch of the Presidio, watching the Hale-Bopp comet and its forked tail over the Marin Headlands. Someone passed around binoculars, somebody else passed a little pipe around, and after a half hour everyone was cold and bored and we drifted back to the battleship-gray Victorian on Haight Street that I shared with a rotating group of five or six pals.

My bedroom was just a large closet on the upper floor, with enough room for a narrow mattress and a chest of drawers left by the previous occupant. But the next room over had work tables and phone jacks for dialing up the Internet, and that’s where I took my Anchor Steam and Camel Lights, because I had an idea.

Heaven’s Gate was a ridiculous tragedy that mixed all the elements of a 1990s Internet Culture that persists today: nerds, Star Trek lingo, web design, UFO reports, mainstream media confusion and the question of “Too Soon?” humor. I had a beta copy of the new WordPerfect, an ancient word processing program, because I was typing up a few chapters for a consumer computing book called something like Using This New Version of WordPerfect. And this software had a new feature called “Convert to HTML” — meaning, I could convert the terrible jokes I’d just been making downstairs into a Web page, on the Internet.

Lots of people I knew were doing tech-writing freelance work in 1997 San Francisco. Most of us were hoping to be famous authors or at least famous journalists, and had returned from various foreign adventures to discover our talents were not in demand. I was terrible at consumer technical writing. It was not at all uncommon for me to stare at the screen for a half hour or so and fall asleep, sitting up. Something had to change.

Around 3 a.m. the next morning, I posted a single-page website called “Heaven’s Gate Action Figures” to the web space provided with my monthly AT&T WorldNet account, sent a few emails announcing this buffoonery, and went to bed. Despite working as editor of a San Diego computer shopper and being a “technology columnist” in Hungary and typing enough free-lance chapters of computer books to afford a budget plane trip overseas every year, this was my first attempt at making a website. It was grotesque, but it was also meant to look like the actual Heaven’s Gate site, shockingly still online in 2013. Meanwhile, the New York Times that thumped against the front door before dawn was full of idiotic op-eds and think pieces about how the scary weird Internet had suddenly gone from “Nerds to Nuts.”

Our Kickstarter was Charlie’s grandmother, who passed away and left him $50,000. This is what we lived on for nearly two years.

The site I made claimed to be the online store for a collection of toys based on the mass suicide of the 39 UFO cultists, featuring the victims in their “Away Team” uniforms and matching Nikes, along with supporting characters of that news cycle: the coroner, the sheriff, and a Tom Brokaw figure whose mic “cannot be turned off.” The web counter broke the next day, as tens of thousands of people visited my AT&T homepage. A week later, this idiotic thing I’d made in the night had more readers than all the stuff I’d published in the previous 10 years.

I said to my writer friend Charlie Hornberger, who was in the computer room with me because it was actually his bedroom, “This is it. We can make our tabloid paper on the stupid Internet.”

For several years at this point, I had been trying to make an updated tabloid newspaper: screaming headlines, smart reporting, great columnists, huge pictures, thrilling world news, scathing exposes, shocking scandals, etc. The last attempt had happened only weeks before the Heaven’s Gate circus, when a local loser had bought a failing neighborhood weekly in our Western Addition/Lower Haight neighborhood and briefly hired Charlie and me to make a great little paper for a community that was mostly ignored by the Chronicle and Examiner. I was fired after submitting my first column, a Jimmy Breslin-esque scene-setter that was mostly about the Palestinian-owned liquor store across the street and a guy who sat on my steps selling stuff we’d just thrown out.

We learned HTML by using Netscape’s “View Source” on the pages spewed out by my word processor. “B” in brackets meant bold, “I” in brackets meant italic, etc. Easy. On the eve of the first issue, I spent two hours drawing an animated gif of a radio tower with the call letters TABLOID in blinking lights — once the name was all lit up, the tower exploded. It was a deeply prophetic mixed media message. Charlie wrote the first story, something about solar flares destroying the technical infrastructure of Earth. There was a “Tabloid Bulletin,” too, about the Pope. I guess I wrote that one.

POOR AND FAMOUS

What happened in the following weeks and months was unlike anything in my previous life. With headlines like MOMMY’S LITTLE SPEED FREAK (about Ritalin) and RUSSIAN DRUNK EATS WIFE’S EAR, people loved Tabloid.net. Especially journalists. And when journalists fall in love with something, they share it with the world.

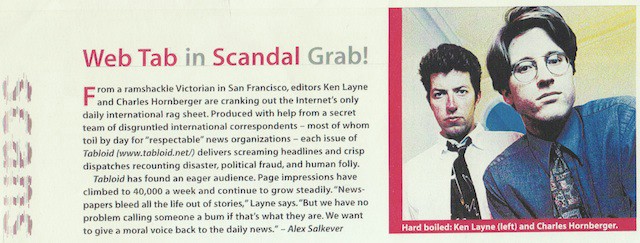

Every night we toiled on the next morning’s issue — Slate had launched the previous summer with a weekly publishing schedule — and every morning I would stagger from my bedroom to the Tabloid newsroom next door to find a growing pile of accolades and write-ups. Along with the “Cool Site of the Day” awards and four-star mentions in the web review columns that had sprung up everywhere, there would eventually be coverage from the Times of London, New York Daily News, Village Voice, Editor & Publisher, Los Angeles Times, TIME Magazine, Entertainment Weekly, even a paragraph-long blurb and a photograph of me and Charlie in Wired. The Tel Aviv daily Ha’aretz named me “one of the Internet’s top authors,” along with Douglas Rushkoff and Jon Katz.

There were TV segments on forgotten cable shows, and a weekly Tabloid.net newscast on a syndicated talk-radio show about the Internet. But our favorite reactions came from like-minded reporters around the world.

Date: Sun, 25 Jan 1998

Ken Layne is perfectly correct in his description of modern newsroom and the witless info-bots who inhabit them. In fact, the domination of the media by whiny, life-sucking drones is an international phenomenon. Tabloid, by the way, is a fine site. Here’s to your first million.

Cheers,

Owen Pike

“Owen Pike” was soon a regular contributor to the site and eventually became Australia’s most notorious right-wing blogger. But his wish for Tabloid.net’s financial success never came true. We had no income at all. Our Kickstarter was Charlie’s grandmother, who passed away and left him $50,000. This is what we lived on for nearly two years. I ate once a day, just before work began at 6 p.m., and mostly subsided off jug wine and cigarettes and the occasional gift of cocaine or deeply appreciated “care packages” of vodka and Camels sent by loyal readers.

The Heaven’s Gate people got some bad information or just processed the regular stuff in the wrong way. But the strangest thing about those sci-fi suicides is how everybody in the still-ascendant print and broadcast media took a cult tragedy and turned it into a war cry against the Internet.

Despondency set in. One night I was making a fresh pint glass of vodka and grapefruit in the kitchen downstairs when a vial of LSD behind the ice tray plopped onto the floor. I picked it up and noticed the plastic cap was halfway off, a blob of chemical slush around the top. I shrugged and swallowed it and went back to work, finishing a rewrite about civil war in the Congo before waves of white-blue light began shooting from my fingers. I stood unsteadily with both hands flat on the worktable and very slowly said something along the lines of, “I don’t think I’m going to finish my column tonight.” By the time I’d made it the four feet to my sleeping closet, the prior reality had crumbled completely — I remember falling to the thin mattress and then existence was strictly on the molecular scale. Hours later, when I had returned to human form and was lounging on the stone patio of some temple on a river, the shadowy dual panther-sisters showed me a a floating screen of all human history, present and past. A flick of your finger at any point along this shimmering panorama would generate a three-dimensional popup so you could experience any specific moment, in real time. I saw several little scenes like this: bird’s eye views of forgotten skirmishes on horseback, the mundane misfortune of a family pushing a broken mini-pickup along some Saharan road. The lesson here is: Don’t do drugs at work.

Charlie kindly went across the street to O’Looney’s and bought me a pack of smokes and a liter of water, leaving them outside my bedroom door. As for the awful Sheryl Crow CD going on repeat from his Mac’s CD player that night, I never did find out if that was intentional torture — but I can still hear some of those songs, deep in the well of my soul. Actually, it must have been on purpose, punishment for leaving him to finish the issue himself that night. We listened to a lot of questionable music in the 1990s, but Sheryl Crow was never on that dubious list. Years later, hearing her perform these songs live at Barack Obama’s nominating speech at Denver’s football stadium, I was forced to leave the seats and sit out on the walkway.

The reason Tabloid’s loyal readership didn’t lead to income is that Internet advertising was just being invented in the late 1990s. We had a friend at one such Bay Area startup, called Flycast, and she invited us to meet the people and get signed up. The revenues were tiny and the technology young. We never got more than a couple of hundred dollars a month, toward the end of Tabloid’s existence as a daily publication, and that ended abruptly when a fat-acceptance group in Berkeley launched a boycott over our rude headline about an obese would-be subway driver who was unable to fit inside the MTA’s training simulator. The Internet is really just the same manufactured outrage, over and over, forever.

Tabloid.net vanished. I let the domain expire about a decade ago, when I didn’t have enough money for the renewal. The domain farm that owns it today has blocked the Internet Archive from keeping the old site, so the entirety of 700 daily editions and thousands of articles and columns is long gone. But Tabloid’s people are still around, for good or ill, and you may have been amused or offended by their works in recent days. Matt Welch is editor of Reason Magazine, a very good magazine that makes very bad excuses for amorality, and Jason Ross is a best-selling author and Emmy winner for his work on “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart.” The aforementioned “Owen Pike” is Tim Blair, the notorious right-wing pundit of Australia and my Counter-Earth twin. Charlie wised up and became a well-paid programmer, now living in Berlin.

Then there was the British-Hungarian journalist who befriended Charlie in Budapest just after I’d left that town. He looked us up after moving to the Bay Area himself, to cover Silicon Valley for the Financial Times. Like plenty of young reporters looking for something more exciting than a 1990s newsroom, he loved Tabloid.net. Loved it enough to offer us a little money to shut it down and go to work for him. The journalist sent to cover Internet startups was starting up his own companies.

I was righteously outraged that anybody would want to kill Tabloid, and we turned him down. By 2005 I was working for his variation on the theme, called SPLOID, and in 2006 I wound up editing his political blog, Wonkette. Nick Denton had left San Francisco for New York and started his own batch of snarky news sites. He found a talented young blogger named Elizabeth Spiers to write and edit the new Gawker.com. As was the fashion in 2002, Spiers’ personal site listed her “blogfathers” as Tim Blair and Ken Layne. It is hard to imagine a publisher other than Nick Denton thinking positively of that association.

The Heaven’s Gate people got some bad information or just processed the regular stuff in the wrong way. But the strangest thing about those sci-fi suicides is how everybody in the still-ascendant print and broadcast media took a cult tragedy and turned it into a war cry against the Internet — if suicidal nerd weirdos could just get on the Internet, maybe we were better off sticking to newsprint and local newspaper reporters with graduate degrees. It was cute before, this World Wide Web, but now it was turning everybody into dangerous space nuts. The anti-Internet hysteria is mostly forgotten now, but it got bad enough in 1997 for the New York Times to repeatedly address the crisis:

In this wilderness-of-mirrors, a single string of mutant thoughts can be replicated over and over, distorted in the Internet funhouse until the result is impossible to untangle. Somehow the slick design of Web pages — so easily accomplished with a few dabs of Java and a cursory knowledge of the computer language called HTML — adds credence to outlandish ideas.

Confusing medium and message in a way that might have made Marshall McLuhan sick, people don’t want to remember the obvious: that all the alarming things on the Internet have been around forever.

From the September 1997 issue of Wired, text by Alex Salkever, photo by Thor Swift.

Previously: Help Wanted: Seeking Young Hemingway To Cover Retired Americans In Belize

Ken Layne has held approximately a hundred media jobs around the world. He should’ve learned by now.