Toile Chic

by Colette Shade

In high school, I envied a girl named Maddie because she owned a black toile handbag. If this sounds like an impossibly stodgy sartorial choice for a teenager, it’s worth pointing out that at my school, the implicit goal for many students was to dress like fifty-year-old country club members, in boat shoes and plaid sport coats and boxy Lilly Pulitzer shift dresses. It made sense: Many of them were already country club members, at L’Hirondelle or Maryland Club or BCC. They were simply getting a head start on their birthright.

Stodgy is the aesthetic that toile trades in. It’s part of the preppy interior design canon, decorating homes from Palm Beach to Bar Harbor, operating as a cipher for a certain kind of wealth. To some, toile’s monochrome peasant figures are ugly or peculiar, but no more culturally weighted an interior decorating choice than flocked wallpaper or avocado green appliances. But to those in the know, toile evokes squash games, engraved silver, lobster rolls in Nantucket, monogrammed L.L. Bean Boat and Totes coated with horsehair, and the kind of insouciance one feels when possibilities and respect are a foregone conclusion.

It’s strange but telling that affluent people continue to decorate their homes with images of happy poor people. Toile seems to hang in stately living rooms as a reminder that everything is okay, showing wealthy people how idyllic poor people’s lives can be. My parents hate toile, but have curiously never gotten around to changing the living room curtains that were there when we moved into our Baltimore home fifteen years ago. In the middle of the house, in blood red ink on ecru cotton, a clump of French peasants eats apples beneath a tree, a young boy tends to a goat, and a comely farm girl hikes up her crinoline to feed some chickens, her bosom spilling over the square neckline of her dress. When I look at those curtains, I often think of the men who come to mow and weed my parents’ yard, sweat beading on their brows in the summer humidity.

Toile’s origins are not nearly as striking as the fabric itself. The fabric’s full name, toile de Jouy (French for “cloth from Jouy”) is not a title used by textile experts, but rather a moniker embraced by decorators to denote monochrome figural prints. The style developed out of imported wood block prints from India, which became popular via trade in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

But there is a man whose name has become almost synonymous with toile: Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf, whose story is equal parts Protestant work ethic and Ancien Régime materialism. Oberkampf was born to a family of Lutheran textile dyers from Württemberg. In 1759, he opened a cotton printing factory in the French town of Jouy-en-Josas, employing painter and engraver Jean-Baptiste Huet as the house designer. “His is one of the very few business that is well-documented,” Linda Eaton, the director of textiles at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware, told me. “The records from others rarely survived, or are very difficult to understand and get access too. That’s why a lot of the historical precedent is focused on Oberkampf.”

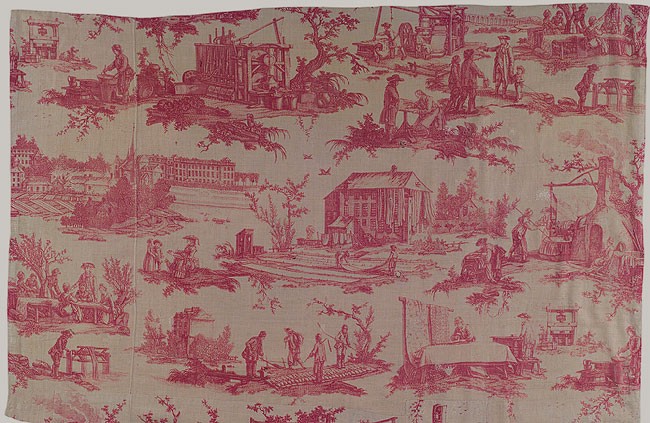

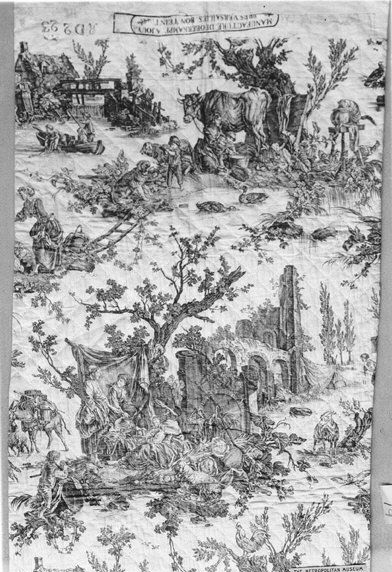

Oberkampf’s factory began production in 1760, using engraved wooden blocks to print images on cotton cloth. In 1770, Oberkampf imported a new printing technology from England and Ireland: Copper plates, which were more efficient than wood. “Printed subjects closely reflected topics in popular culture of the period,” Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Melinda Watt said. “For example, the experiments with hot air and helium balloons in the seventeen eighties prompted the design of several versions on printed cotton. Contemporary literature, opera, and theater were illustrated. There is also more than one version commemorating the death of philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.” And one absurdly meta design, The Activities of the Factory, depicts the process of cloth printing at the Oberkampf Manufactory, complete with images of Huet sketching, dyers mixing pigments, and printers applying ink to the copper plates.

The fabric’s success allowed Oberkampf to become wealthy himself. Oberkampf’s newfound wealth earned him a patent of nobility from Louis XVI and the patronage of Marie Antoinette. The industrialist parlayed his toile empire into political power, becoming the first elected mayor of Jouy. By the time his factory closed in 1843, it had produced around thirty thousand unique designs.

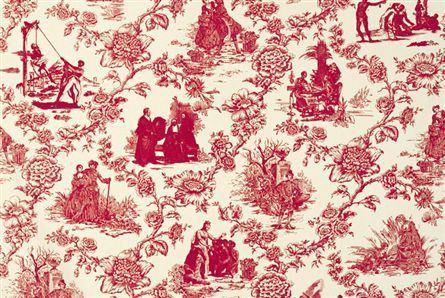

Among the most prolific and enduring subjects was the pastoral. A typical example is Pleasures of the Farm, from the late seventeen eighties. In this pattern, much like the curtains in my parents’ living room, a pretty farm girl feeds a flock of chickens, a woman and her young boys tend to cattle, and two peasants dance beneath a tree. Such patterns were a hit with the French aristocracy and bourgeoisie, who used it to decorate rooms ensuite, the same pattern adorning bed linens, window treatments, walls, and upholstery. The soothing pastoral scenes could transform a stately bedroom into a womb of rustic sophistication.

But toile’s cheerful imagery belied France’s fomenting revolution. Most French people were subsistence farmers whose poverty was exacerbated by heavy taxes and feudal dues. In 1775, poor harvests and rising grain prices led to nationwide riots. These real life starving peasants were a stark contrast to toile’s cheerful, monochrome pastoral images. In 1788, another bread riot broke out, this one flavored by a growing dissatisfaction with the French monarchy. And in April 1789, just months before the July 14th storming of the Bastille, a riot broke out over proposed wage cuts at the Réveillon wallpaper manufactory. It is unknown whether Réveillon produced toile wallpaper. But, if you had enough money to afford toile of any kind, it could provide a comforting justification for the status quo, right there in your home.

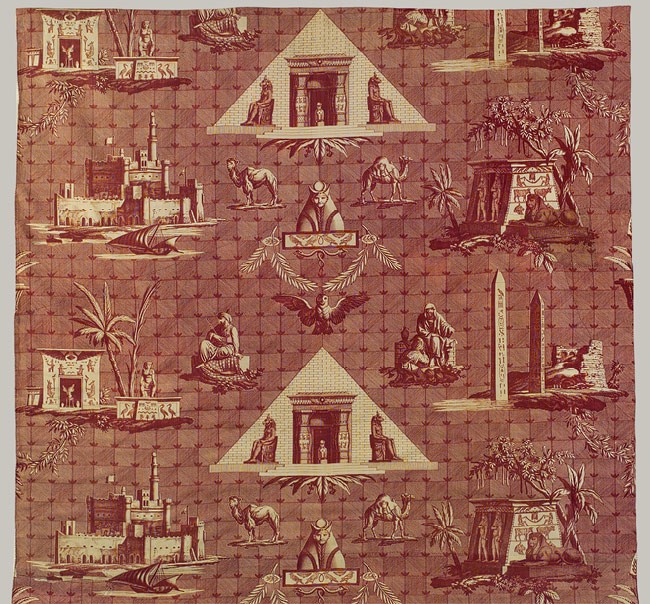

Another popular subject was France’s burgeoning colonial empire. “Exoticism in the decorative arts and interior decoration was associated with fantasies of opulence and ‘barbaric splendour,’” Sara J. Oshinsky of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum wrote in her 2004 article “Exoticism in the Decorative Arts.” According to Oshinsky, Napoleon’s 1798–1799 campaign in Egypt and Syria — covered extensively in French and English language publications — had a major impact on the decorative arts. The imagery inspired by this campaign was the stuff of Edward Said’s nightmares. In 1808, the Oberkampf manufactory produced a toile pattern called The Monuments of Egypt, which features camels, pyramids, and seated, anonymous Arab men in robes and keffiyehs. And during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, France colonized large portions of North and West Africa, the Levant, and Southeast Asia. With this growing colonial empire came fresh representations of non-Europeans as a dark, indistinguishable horde of the exotic, the decadent, the uncivilized.

Many toiles were done in a style known as chinoiserie, which filters East Asian themes through the lense of European decorative arts. A typical iteration are two unnamed Oberkampf patterns from 1770 and 1786, which both depict pagodas, bamboo, palm trees, and figures in nonspecific East Asian dress. A toile from an Alsatian factory, produced sometime between 1825 and 1830, depicts East Asian figures (again of vague origin) naively frolicking. French missionaries and merchants had been attempting to “civilize” the people of Vietnam since the mid-nineteenth century, and in 1859, France invaded Saigon, kicking off a century of brutal colonial rule in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

According to Linda Eaton, there were a few toiles that featured progressive political messages about abolishing slavery and supporting the American Revolution. But the fabric business, like any business, catered to consumer demand, so the output of such designs was limited. So how did toile find its way from France and its colonies to a living room in Baltimore? Stateside, French decorative arts have been prized since the beginning. “French influence in American decorative arts probably owes to the influx of French refugees following the French Revolution and the back uprisings in Haiti,” writes Florence M. Montgomery in her 2007 book Textiles in America: 1650–1870. Fashion magazines, according to Montgomery, also spread French fashion and decorating trends.

And in the world of fabric, everything comes back into fashion. “Nothing disappears, and nothing appears out of nowhere. Just as the individual pattern repeats incessantly over the course of a print run, its motifs are in repeat over the course of the decades,” writes Susan Meller in her 1991 book Textiles Designs: 200 Years of European and American Patterns. The same could probably be said of interior design in general. If you visit Mount Vernon — which boasts a toile-upholstered canopy bed, chairs, and curtains in one of its many bedrooms — it doesn’t look fantastically different from many contemporary homes. The fringed curtains, lyre back chairs, and rococo mirrors could all be encountered today. Like these objects, toile never really fell out of favor, and was further buoyed by several Colonial Revival periods in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

“The Colonial Revival movement, with its roots in a distant past, has helped successive generations of Americans ease the transition into the newness of the present and the uncertainty of the future,” architectural historian Dr. Dale Allen Gyure writes in his essay “The Colonial Revival: A Review of the Literature.” “In architecture and furniture design, the qualities of ‘refinement and dignity’ found in colonial examples, along with simplicity and proper proportions, linked colonial styles to the balance, symmetry and proportion of classical architecture. Interest in the Colonial Revival was therefore equated with timeless good taste.” Figural toiles have thus endured just like other patterns — stripes, floral toiles, ginghams. But figural toiles have a lot of visual content. Any ideologies transmitted by stripes, florals toiles or ginghams would be hard to parse. Plus, those patterns are used too broadly and possess connotations too diluted for any kind of meaningful sociological read. Toile is extremely niche-y, connoting specific places, eras, and classes. Toile, along with Chippendale furniture and Federal architecture, offer a distinctly Colonial look, in more ways than one.

The artist Renée Green took toile’s colonial connotations literally in her 1994 work Mise-en-Scène: Commemorative Toile. In red on white, moments from France’s early colonial empire are depicted. Louis XIV signs the 1685 Code noir laws, sanctioning slavery in France’s West Indian colonies. Haitian revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessalines hangs a French officer during the country’s fight for independence between 1791 and 1804. For exhibitions, Green decorated a room in the traditional ensuite manner, upholstering chairs, a lamp shade, and the wall. The effect is at once homey, luxurious and, when examined in detail, disconcerting.

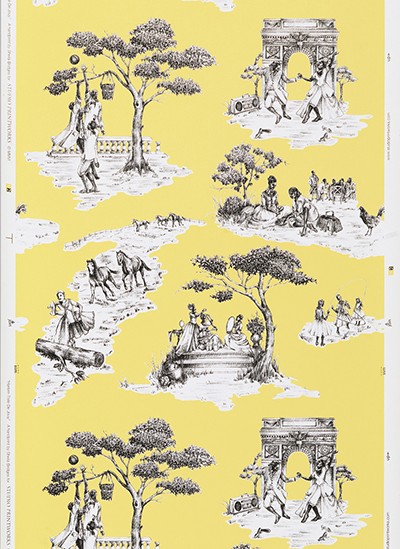

Interior designer Sheila Bridges put another modern spin on toile with her print Harlem Toile de Jouy. “After searching for many years for the perfect toile for my own home, I decided that it quite simply didn’t exist,” Bridges writes on her website. “I created Harlem Toile de Jouy to thread my own satirical story that lampoons some of the stereotypes deeply woven into the African American experience.”

Like the original toiles, Harlem Toile has monochrome figures in eighteenth-century garb enjoying simple pleasures. But the figures are black, and the pleasures — dancing, basketball, fried chicken — carry distinctly racist overtones. Bridges takes images that most people know to be racially prejudiced and puts them in the context of something quotidian, making a point not only about the stereotypes themselves but about the insidiousness of racism, about toile, about the power of everyday objects in shaping the way people see the world. Objects — even ones that seem beautiful or benign — communicate ideologies and narratives, and sometimes those ideologies and narratives are ugly and oppressive and violent.

Toile has also inspired more lighthearted, less overtly political interpretations. Textile artist Richard Saja, who embroiders on toile fabric from decorator stores, puts blue mohawks on women, cockroaches on flowers, and clown noses on cherubs. Glasgow design firm Timorous Beasties has created dozens of toiles depicting streetscapes in New York and London, pigeons, and clouds. Former Beastie Boy Mike Diamond designed Brooklyn Toile with boutique wallpaper house Flavor Paper to decorate his Cobble Hill townhouse. The wallpaper features images of the Brooklyn Bridge, the Notorious B.I.G., and Coney Island’s Cyclone roller coaster. These appropriations aren’t so much calling into question the politics of aesthetic norms as broadening the topics they depict. But their existence demonstrates how iconic toile’s imagery has become, and perhaps why it is so appealing.

Recently, I came across a photograph of the musician Panda Bear, born Noah Lennox. He wears a green and white toile t-shirt and stands in front of a matching backdrop. Lennox grew up in Roland Park — a neighborhood not far from my parents’ house and my high school — where the houses have been in some families so long that they have covenants forbidding blacks and Jews from moving in. I couldn’t help but think that the photo shoot was a cheeky nod to his tony upbringing. After all, he named his latest single “Boys Latin,” a reference to a local prep school with a star lacrosse team and twenty-five-thousand-dollar-a-year tuition. Lennox is a soft-spoken experimental musician with an ear for the psychedelic, not a lax-playing elitist. He’s not decorating with toile to prop up his belief in the status quo. But it’s likely he grew up with the fabric, its imagery woven into his subconscious. I wonder if it makes him think of gardeners, hunched over flowerbeds in the hundred degree Baltimore heat.