The Husband Did It

by Alice Bolin

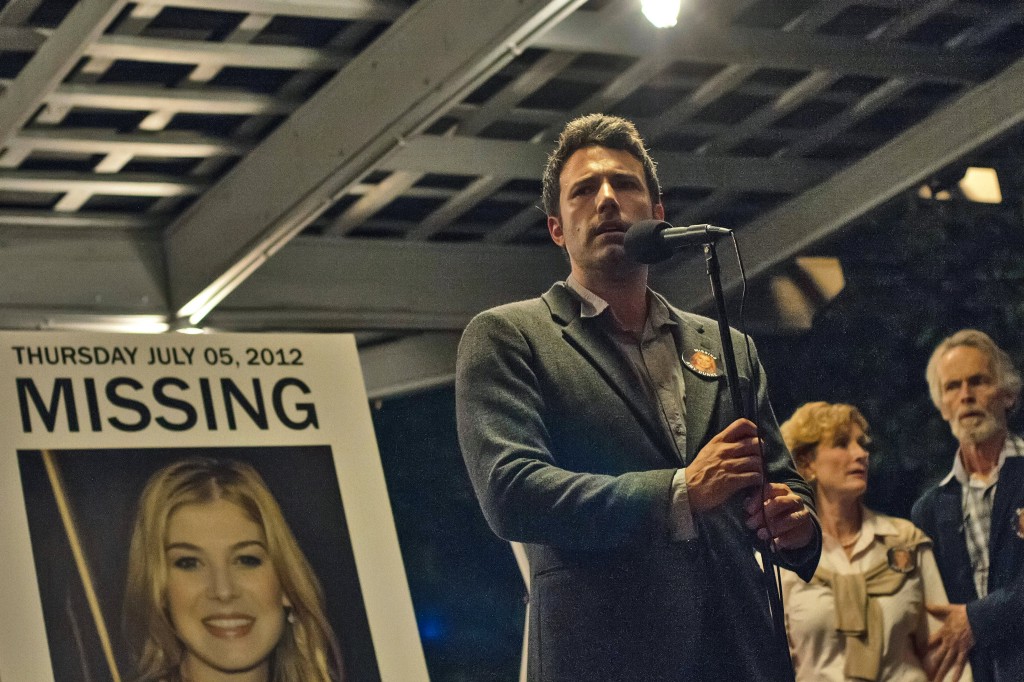

“It’s always the husband. Just watch Dateline,” Gillian Flynn writes in her novel Gone Girl, telling a public who gawked through the OJ Simpson and Scott Peterson trials what they already know. Flynn’s novel, along with David Fincher’s faithful 2014 movie adaptation, is the subversive American noir of the Court TV era. It features two remarkably odious narrators: Amy Dunne is cruel, self-important, and vindictive, as she meticulously frames her husband for her own murder to punish him for cheating on her. Her husband, Nick Dunne, is self-pitying and self-deluded. Told by these two exaggerated voices, the story is a pulpy, shameless thriller, theatrical in every element, including its self-conscious interest in true crime television and the trope that spawned its premise.

To plan her crime Amy watches shows about police procedure and reads true crime books, luring Nick into doing classically suspicious things like taking a life insurance policy out on her. And once Nick is under suspicion, he tries not to do anything that would fit Dateline’s picture of “guilty.” “I knew from my shows, my movies, that only guilty guys lawyered up,” he says. Gone Girl depicts the true crime obsession as a feedback loop — “Serial killers watch the same shows we do,” one of the detectives says — and Amy sees in them a chance to transfigure herself. She makes herself the author of her own narrative (literally, in the falsified diary that forms her early chapters of the novel), a narrative where she was “the hero, flawless and adored,” she writes. “Because everyone loves the Dead Girl.”

What else could she gather from the proliferation of true crime stories on television, from news magazine shows like 20/20 and 48 Hours to Court TV — originally a C-SPAN for salacious nineties court cases, which “came into its own during the Menendez brothers first trial and later during the O.J. Simpson murder trial” — thanks, Wikipedia — and is now reaching its gleeful, febrile, shameless apex. Reborn in 2008, the cable network Investigation Discovery (formerly Discovery Times, formerly Discovery Civilization Channel, formerly Discovery Civilization Network: The World History and Geography Channel), is now all murder, all the time. A sample of its current programming: Beauty Queen Murders, Catch My Killer, Deadly Devotion, Motives & Murders, Nightmare Next Door, Murder.com, Unusual Suspects, and Wives With Knives.

If you watch enough hours of real murder television you experience a peculiar déjà vu — despite what would seem to be a wellspring of new cases, the same murders are recounted again and again, migrating through Investigation Discovery programming blocks. The story of Clearwater, Florida airline gate agent Karen Pannell, who was murdered by her ex-boyfriend Timothy Permenter in 2003, has been on Dateline, Forensic Files, and the Investigation Discovery original program Solved. The most memorable fact of the case is that Permenter wrote “ROC,” the name of another of Pannell’s exes, in her blood on the wall above her body, lamely attempting to forge a “dying declaration.” This detail gives it the feel of a whodunit. In interviews on Dateline, Forensic Files, and Solved, detectives emphasize, again and again, the gruesome glamour of this clue: “It’s not something you’ll typically see in a homicide case”; “It’s more likely something you’ll see in a TV show or in a movie”; “It was like something you’d expect out of a Hollywood movie”; “It’s like something out of the movies.”

It’s a clue that announces itself, like the ones in Amy’s sinister scavenger hunt in Gone Girl that lead Nick and the police to all the evidence she has planted. The grotesque melodrama Amy orchestrates is prodigious, but still I found her more sympathetic than Nick, who is so convinced that he has tried, at every moment, to do the right thing. His father was an abusive misogynist, but Nick says, “I’ve tried all my life to be a decent guy, a man who loved and respected women, a man without hang-ups.” When his issues with women do leak through, like when he becomes momentarily furious that a female detective is telling him what to do in his own home, he blames it on being raised by his father and thinks his self-awareness will absolve him. He is the classic male victim. Even his misogyny is something that was done to him. This is why Nick’s is the more damning characterization: because Amy bears no resemblance to any person who has ever walked the planet, but she bears a resemblance to women as conceived of in the nightmares of men like Nick, and there are many of those men walking the planet. For “decent” guys like Nick, comfortably vested with patriarchal authority, the nightmare is to no longer be the narrator of their own story. In Gone Girl, Flynn cracks open the culture and lets Nick say one of our unsayable beliefs: that it is scarier for a man to be accused than to be killed.

The noir genre was borne from the economic upheaval and disenfranchisement of Prohibition and the Great Depression, which has everything to do with its function as, in Sarah Nicole Prickett’s words, “a grim and slippery indictment of American masculinity.” When has the masculine fantasy — The American Dream? — been about anything other than control, about taking what’s yours, in sex or in business? Prickett, in her brilliant n+1 essay on the May 2014 massacre at UC Santa Barbara, “The Ultimate Humiliation,” writes about the ways that violence against women is so often connected to men’s professional and financial frustration. “It’s hard not to think these killings might have been slowed, might even have been stopped,” she writes of the Santa Barbara murders and others, “if more members of what is generously called ‘the system’ had the slightest acuity, maybe a little bit of feeling for a pattern, when it comes to fallen, immobilized men and their as-ever easiest targets.”

In fact, identifying patterns is exactly what it takes to prevent domestic violence murders — and they can be prevented. Amesbury, Massachusetts’ Domestic Violence High Risk team, founded in 2005, seeks specifically to prevent domestic violence homicide, and they’ve been remarkably successful, cutting the number of domestic violence homicides from one a year in Amesbury — a town of only sixteen thousand people — to zero in the nine years of its existence. They coordinate the efforts of the various agencies that deal with aspects of domestic violence cases, and they try to disrupt the behavior of the abusers, rather than disrupting the lives of the victims by relocating them to shelters. They determine the risk that a domestic violence case will escalate to murder by assessing for a number of red flags. In a July, 2013 New Yorker article profiling the Domestic Violence High Risk Team, Rachel Louise Snyder describes how the risk of murder is closely correlated to moments of upheaval, “spiking when a victim attempted to leave an abuser, or when there was a change in the situation at home — a pregnancy, a new job.” The High Risk Team’s list of risk factors includes, tellingly, an abuser’s chronic unemployment; we hear in passing towards the end of the Karen Pannell episode of Solved that Timothy Permenter had quit his job the day of her murder.

It is chilling how closely Pannell’s case mirrors the High Risk Team’s domestic homicide cases. She had broken up with Permenter a few weeks before; she told her family he had choked her and she was afraid of him; she called the police ten days before her murder because he was stalking her. (She also had a history of domestic violence with Roc, the boyfriend Permenter framed, though he assures the host of Dateline, “She gave as good as she got.”) Permenter had an alarming past, having spent twelve years in prison for attempted murder after a gunfight with the owner of a rival escort service — the shows feature lurid photos of a blurry tattoo on his arm that reads “Escort King.” The break up, the incidents of domestic violence, Karen’s contact with the police, and Permenter’s criminal history are all on the High Risk Team’s list of risk factors. But on the murder shows, all these facts are elided or saved for the end of the episodes; at the beginning, it’s all about the crime scene, the clues, and the giant letters written in Karen’s blood on the wall; we hear the story of the murder as Permenter wanted it to be told.

On Solved, the detectives describe the change in Permenter after he realizes he has not gotten away with Pannell’s murder: “his demeanor… changed from this very cooperative, very talkative person to dark, quiet, angry person.” This kind of transformation must be a common sight for the legion of detectives and other authorities who still lack a feeling for the pattern. Snyder quotes from the coordinator of a group counseling organization for domestic abusers who emphasizes that abusers usually seem normal and even likable; their partners become the focus for all their rage, so it rarely seeps into other areas of their lives. “I didn’t hate and fear all women,” Nick says defensively in Gone Girl. “I was a one woman misogynist. If I despised only Amy, if I focused all my fury and rage and venom on the one woman who deserved it, that didn’t make me my father.” Aren’t they all one-woman misogynists? When you consider that, as Snyder writes, “the Justice Department estimates that three women and one man are killed by their partners every day,” and that “between 2000 and 2006… domestic homicide in the United States claimed ten thousand six hundred lives,” it’s no wonder that true crime fans roll their eyes at the predictability, that the husband did it. It’s never a mystery.

On the flip side of Gone Girl’s sensational pulp is the meandering minutiae of the podcast Serial. In it, This American Life reporter Sarah Koenig delves with eccentric myopia into the details of a 1999 Baltimore murder case in which then eighteen-year-old Adnan Syed was convicted of killing his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee. Koenig becomes particularly obsessed with the obvious inconsistencies in the story of the state’s star witness, Adnan’s friend Jay, who claims he was enlisted by Adnan to help him bury the body. Koenig is clearly disturbed by how much dishonesty and uncertainty the criminal justice system allows for before ceding reasonable doubt. She consults Jim Trainum, a former Washington D.C. detective who now is an advocate for preventing false confessions. He acknowledges that while the inconsistencies in Jay’s story are worrying, Koenig must also “look at the consistencies.” In an interview with The Intercept after the podcast ended, the case’s prosecutor, Kevin Urick, said essentially the same thing, insisting that witnesses rarely give a perfectly honest testimony, but that Jay’s testimony on “material facts” was consistent and backed up by other evidence.

“The cops probably settled for what was good enough to be the truth,” Trainum tells Koenig on Serial, and from Urick’s statements, this is what happened. Trainum’s main warning to the police forces he trains is to watch out for verification bias, that is, only looking for evidence that fits their preconceived story of the crime. But that picking and choosing, the arranging of compelling details, is the very basis of our justice system: “the case,” which is not a compendium of all the evidence about an event, but a rhetorically convincing narrative of the event. “Trials are won by attorneys whose stories fit,” as Janet Malcolm writes in The Crime of Sheila McGough, “and lost by those whose stories are like the shapeless housecoat truth, in her disdain for appearances, has chosen as her uniform.” Koenig recognized that the state’s story of the crime was not the truth, but the shapeless, contradictory, and hopelessly incomplete truth she discovered did not satisfy her either.

It is easy to see why this tricky relationship to the truth is worrying, given that police and prosecutors’ offices are powerful organizations that are heavily invested in maintaining an essentially unfair social order, and that the presumption of innocence is a farce that cannot overcome juries’ psychological biases. One of the more tone deaf moments of Urick’s Intercept interview is when he dismisses the notion that racism against people from the Middle East could have played a part in Adnan’s conviction, saying, “This was well before Sept. 11. Nobody had any misgivings about someone being Muslim back then.” It is obvious that prosecutors’ story of the crime contained racist language and stereotypes. “He felt betrayed that his honor had been besmirched,” Koenig quotes from Urick, as he sounded a dog whistle. Serial’s crazy popularity seems to have an implicit connection to the biggest news story of last year, the lack of indictments in the cases of white policemen who shot and killed unarmed black men. What was so baffling and depressing about those stories was that grand juries refused to even let the cases go to trial — in order to preserve privilege, it was crucial to preserve the image of who is a criminal and who is an authority. Clearly, there is damage done just by raising the question.

When a cop kills an unarmed man, it is because he senses his power being threatened by fear that he should never have to feel. When a man kills his ex-girlfriend because she leaves him, he is saying the same thing: shame and sadness are things I should not have to feel. What is ultimately frustrating about Serial is that it conflates a mistrust in unfair legal narratives with a mistrust in patterns that are all too real, namely “the most time-worn explanation for [a woman’s] disappearance: the boyfriends, current and former.” A skepticism that the husband did it shows a weird, classically American disdain for both authority and the powerless. But if the last year proved anything, it was that there are endless opportunities to misapply victimhood.

On Dateline one of Karen Pannell’s friends says that she was “pretty, smart, smiled all the time.” At the end of the episode, the voiceover says that she “loved her friends, loved the beach, and died too young.” On Serial we hear that Hae was athletic, outgoing, and funny, but after the second episode, where we hear excerpts from her diary, she disappears from her own story; from then on, it’s all about Adnan and Jay, the evidence, the trial. But of course, that’s why we love her: because she’s dead, and her death is the catalyst for the fun of sleuthing. It’s why Forensic Files spends so much more time on debunking Permenter’s obviously bogus clue, the message written in blood, than describing his history of abuse. I was more and more astonished reading the episode synopses from Netflix’s Forensic Files collection: “When a woman’s body is found in a burned-out house, microscopic clues on a piece of pipe help determine whether her death was an accident or murder;” “When a woman is raped and murdered on the beach, investigators track down the killer through a pair of shoes left near the body;” “At an apartment where a mother was stabbed to death, investigators find plenty of evidence but have no suspect to compare it against.” It’s clear we love the Dead Girl, but we don’t empathize with her. If we did, we might ask why we did nothing to protect her — why we, as Prickett writes, “make these crimes by emasculation feel as common, and unstoppable, as acts of god.”