The Picasso In Her Closet

The inheritance that wasn’t.

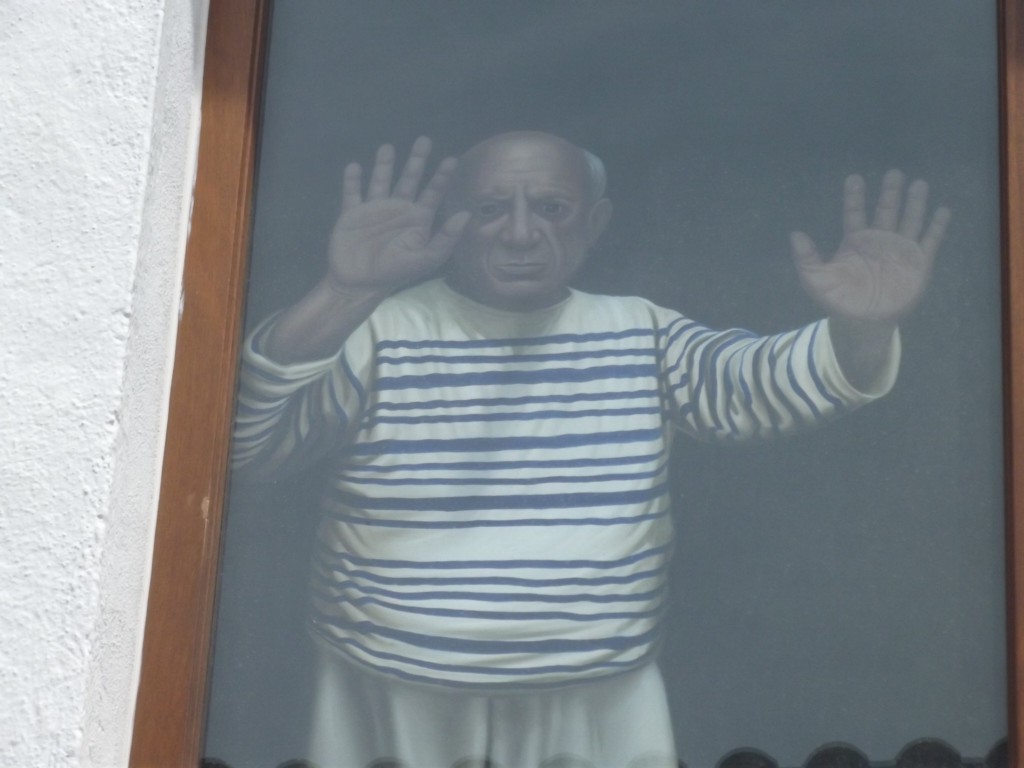

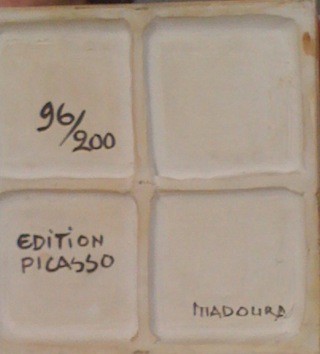

My mother was dying, so she couldn’t hold on to Ann-Marie’s Picasso any longer. I should tell you: this wasn’t Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It was a small square tile — one of Picasso’s Madoura pottery pieces and part of a series of two hundred, according to its back. On the tile’s surface was a simple human face: loop eyes, slash mouth, yellow pickle-ish nose, single red blob suggestive of a cheek, all set on a plate-like white circle like a hastily prepared meal. By Picasso, though.

My mother was holding on to the Picasso for her childhood friend, Ann-Marie (this isn’t her real name), who had told her that she had multiple chemical sensitivity, a physically debilitating reaction to what she considered toxins in the environment. Online there’s an intricate support network of MCS sufferers of which Ann-Marie became a part, but there also exists a grousing community of doubters who think that MCS is a manufactured malady.

The American Medical Association and the World Health Organization don’t recognize MCS as a bona fide illness, and neither did my mother. She forwarded me, her only child, some of Ann-Marie’s emails about living with MCS, including one from 2007 in which she complained of electromagnetic frequencies, which she said made it hard for her to use her cell phone. At the top of Ann-Marie’s email, my mother had written this to me:

See her message. I honestly don’t know what to say to her. I think she is a nutcase. Maybe just go along with her and be sympathetic like we did when my mom had dementia.

Later she emailed me,

Ann-Marie was pre-med in college, and I want to ask her what empirical evidence there is to support her electric sensitivity diagnosis. What causes it? What specific symptoms? What is the correlation?

For Ann-Marie, having MCS eventually meant being peripatetic, by which time she asked my mother to mind her Picasso. Ann-Marie’s parents — her father had been a wine importer — had purchased the piece as an investment; they’d had only one child, and when they died, it was hers.

I first saw the Picasso when Ann-Marie showed it to me at her West End Avenue apartment in the mid-1980s — this was well before her MCS self-diagnosis. My mother and I were down from Boston to look at prospective colleges for me. She and Ann-Marie, who was in advertising and had done a L’eggs commercial that I’d actually seen on TV, had met when they were twelve, at a camp in Maine about which they were jointly evangelical their entire lives. I’d hated camp, and being as outdoorsy as Lovey Howell from Gilligan’s Island, I was hell-bent on an urban school.

Columbia didn’t want me and Barnard wasn’t sure, but NYU said they’d try me, so I moved into a Greenwich Village dorm in the fall of 1985. Occasionally Ann-Marie invited me over for dinner. She was divorced and hadn’t had kids, and her single life interested me more than my likewise single mother’s did. Ann-Marie lived alone in a high rise in a two-bedroom, two-bathroom marvel of tidiness with a postcard-worthy view of midtown; she was right around the corner from the Tower Records where Woody Allen and Dianne Wiest seal their fate in Hannah and Her Sisters. One night, Ann-Marie made me dinner and told me about her dating life, and that some guy she was seeing only wanted to “jump my bones.” The expression, which I’d never heard before, rang in my ears.

My mother said that Ann-Marie saw herself as an artist, which was why, when her building went co-op, she decided to stay on as a renter, refusing to purchase her unit even though her inheritance would have made it possible. Her reasoning was along the lines of “A truly free spirit wouldn’t own property.” This decision infuriated my pragmatic mother, and even I, who didn’t consider myself a grown-up yet, registered a self-sabotagingly bad call.

To me, Ann-Marie didn’t seem like an artist — she dressed in the earth-toned tweeds of the advertising executive she was — but of course there was a creative aspect to her job, and she did have cool artwork hanging on her walls, starting but not ending with the Picasso. The last time I was at her place, before my social life at NYU perked up, I saw something new: a series of about a half dozen vertical canvases on her living room wall. One canvas was sheathed in what looked like a light-blue pillowcase. Another featured part of a paper bag. One may have been completely blank. “Do you like them?” Ann-Marie asked me, and I truthfully told her I did. I’d taken to poking around SoHo galleries, and I thought that much of what they were selling was less endearingly peculiar than these pieces.

After I left Manhattan in 1990, my mother wasn’t as likely to visit Ann-Marie as Ann-Marie was to visit my mom in Massachusetts, and if I was living in the state I would pop over. They would trundle out the camp songs, and I would roll my eyes, which was what I assumed they wanted from me. One time Ann-Marie came up to visit my mother with the express wish to see the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, but before she left town she told me in private that my mother had reneged on taking her. Ann-Marie was supremely miffed, which thrilled me. For a flash, she and I were the girlfriends and my mother the odd woman out.

That was Ann-Marie’s last visit to my mother’s place as a healthy person, and probably the last time I saw her. She gave up her West End Avenue apartment, in which she said she felt sick. Because of her inheritance, Ann-Marie could afford to stop working, and she began to search for a home that wouldn’t feel toxic. She tried living in Texas, and maybe some other state, and also here in Massachusetts; they were all botches. She must’ve entrusted my mother with the Picasso sometime before my mom’s first go-round with cancer. Along with the Picasso, Ann-Marie gave her the phone number of some friends, a couple who lived in Connecticut, who could take custody of the piece if for some reason my mother was no longer able.

I suspect that my mother regarded Ann-Marie’s embrace of the MCS party line as something of an upper-middle-class luxury. Once, lamenting Ann-Marie’s lifelong unhappiness, my mother told me that Ann-Marie had been kind of a spoiled little rich girl — she’d even owned a horse. This dig might seem galling coming from my mother, who, like Ann-Marie, grew up rather well-to-do in New Jersey. But my mother probably had a low threshold of tolerance for people nursing can’t-quite-put-a-finger-on-it ailments given that her father committed suicide when she was away at college; if anyone deserved to indulge a psychosomatic illness, if that’s what Ann-Marie had, it was arguably my mother. But she was too practical for that, and anyway, from pretty much the day she divorced my father until the day she retired, she had to work.

Because of the Picasso’s value — to Ann-Marie, sure, but also to the art world — I was apoplectic about how my mother was storing it: swaddled in a blanket in a Crate and Barrel shopping bag. She kept the bag in her storage unit on her floor in her apartment building in Watertown, Massachusetts, and once, after she’d been rearranging things in there, she forgot to put it inside the storage space, so it spent the night in her building’s common hallway. This is a Picasso I’m talking about.

I kept telling her there might be something on that blanket — bleach, maybe — that could erode the surface of the tile, and that there was an entire industry devoted to preserving artwork; we could tap it. One day my mother phoned me to say that she thought I was being controlling on this point and that the way she was storing the Picasso was just fine. I think she thought I was being like Ann-Marie: seeing toxins where there weren’t any.

This was likely our last fight. In 2009, at around the time I contacted a friend at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts about getting advice from professionals on how to store the Picasso, my mother’s cancer came back. She summoned the Connecticut couple.

As cancer whittled away at my mother, Ann-Marie, too, got a cancer diagnosis. She outlived my mom by not quite two years, during which time we occasionally spoke by telephone; she was now living in Dallas, giving Texas a second shot. I’m an anxious telephone talker, but these conversations I liked, both for the obvious, wounded-motherless-daughter reason and because Ann-Marie and I seemed to get each other in a way that my mother, who tried valiantly, never got me, and maybe Ann-Marie’s parents never got her. After I learned of Ann-Marie’s death — her dispersed MCS community of friends had been kind enough to include me in their email chain — I was ashamed of myself for wondering this: might Ann-Marie have bequeathed the Picasso to me?

Of course she hadn’t. Why should she? Ann-Marie was an admirably charitable sort, and I was no charity case. (Recall that my deceased mother, while plenty charitable herself, had been practical, which meant she was a saver, and that I was her only child.) I assume that if Ann-Marie didn’t donate the Picasso, any proceeds from it went, as well they should have, to a favorite cause — environmentalism or animal rights, say. Or to the camp in Maine, which informed me that Ann-Marie, no longer what anyone could call spoiled or rich, had made a substantial contribution in my mother’s name shortly after my mom’s death.

I learned from Ann-Marie’s MCS friends that after she died they found among her possessions many notebooks and journals, some containing her poetry. I’m guessing that she had long ago gotten rid of the canvases she had hung on her living room wall on West End Avenue, and that no one had seen any value in them. At some point after I left New York, my mother told me that it was Ann-Marie herself who had made them — she had admitted this to my mother, but not to me. This smarted. My mother didn’t even like that sort of thing — she liked Manet and Monet. She liked pretty things. Did she even like Picasso? Had I known that Ann-Marie made those pieces, I would have told her that I thought she was on the right track — “Good for you,” or something. What I would have meant was, “Go ahead — be an artist! Give up advertising! You don’t have to get sick to become a free spirit.” As if anyone in adultland would have listened to me.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.