The Poet and His Postcards

by Kaveh Akbar

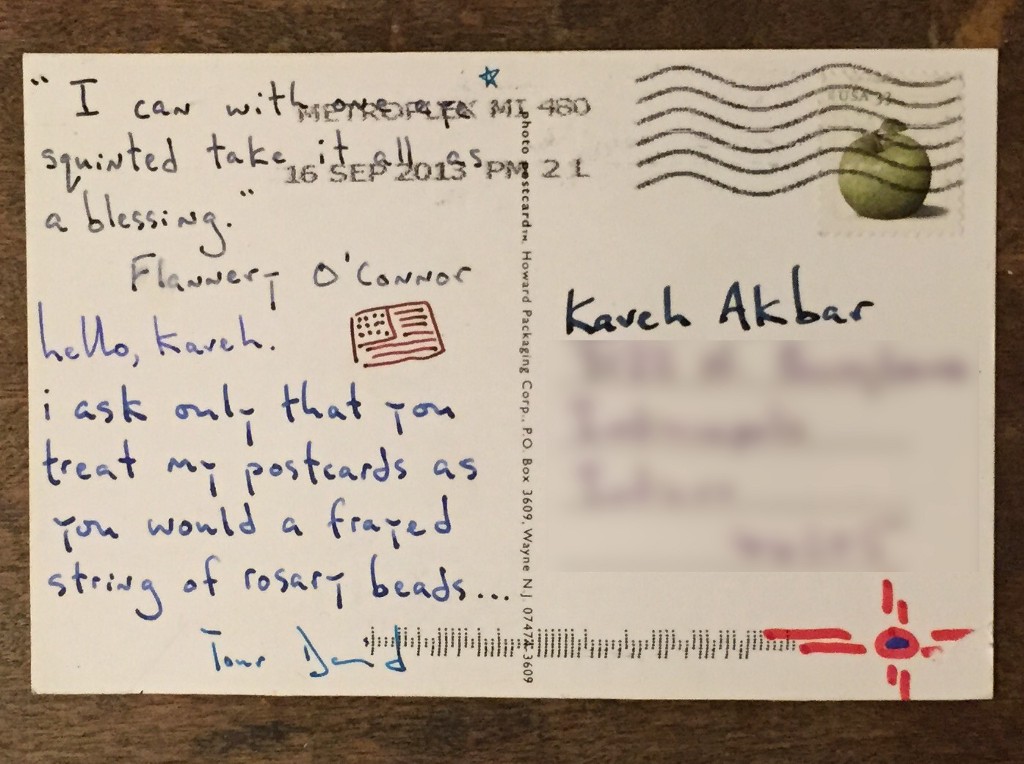

i ask only that you treat my postcards as you would a frayed string of rosary beads…

David J. Thompson has been sending me four or five postcards a week since I was eighteen. I was beginning my undergrad at Purdue, obsessed with small-press poetry the way a child gets obsessed with dinosaurs or construction equipment. He didn’t know me at all, but I knew and loved his poems; they appeared regularly in the little fold-and-staple journals I devoured at the time, magazines like Nerve Cowboy and Staplegun and Barbaric Yawp.

While most writers in that scene were doing bad Bukowski impressions, bumbling around drunken esoteries and humble-bragging about adventures in casual misogyny, Thompson, who lived and taught in a small town near Detroit, wrote poems that were more indebted to William Stafford or Raymond Carver or James Wright. The pieces were rural, domestic, and ribbed with an almost ecstatic desolation. His speakers were down-on-their-luck divorcees, paunchy factory men at their high school reunions, drunk friends marveling over Mexican death masks. I sent him a note saying how much I loved his work; the postcards started arriving soon after, and they’ve never stopped.

Over the last eight years, I’ve received more than a thousand postcards from David. I’ve read and reread every chapbook he’s published, and we’ve even done a couple readings together. Here’s what I know about him: He’s middle-aged(ish), used to teach high school English, and lives and travels by himself. He loves Criterion films, jazz, and The Simpsons. The bio on his 2009 chapbook It Gets Worse notes that he enjoys “beer and minor league baseball, especially together.” He lists Chet Baker, Robert Capa, and Brooks Robinson as his heroes. A few years ago, he survived cancer after having most of a lung removed. During readings, he stays quiet, typically a huge camera between himself and whatever is happening at the time. One time, at a reading at Notre Dame, still honeymooning with my new ability to drink legally, I got a little brazen with my drink tickets. David quietly slipped me twenty dollars for a taxi, instructed me to have a messy night, then ducked out to drive back home.

But much of his life remains a mystery: Ninety-eight percent of the conversation between us has moved in a single direction, from him to me. I have no idea where he grew up, if he’s ever been married, or if he has kids. He constantly travels around the country, often to famous gravesites (Jimi Hendrix, James Dean, Edna St. Vincent Millay), but I never know where or why he’s going.

Aside from a modest website for his photography, David doesn’t exist on the internet. He doesn’t have a Twitter or a Facebook or even an Instagram for his photos. As far as I can tell, he channels any documentarian impulses he might have into his art. He takes photos and writes and synthesizes it all into his postcards. I have no idea how many other people get cards from him, but it seems to me that those of us in the exclusive club of postcard recipients are privy to one of the most interesting “social media” streams conceivable — a routinely updated feed of visually striking, intellectually compelling, tactile, personalized content.

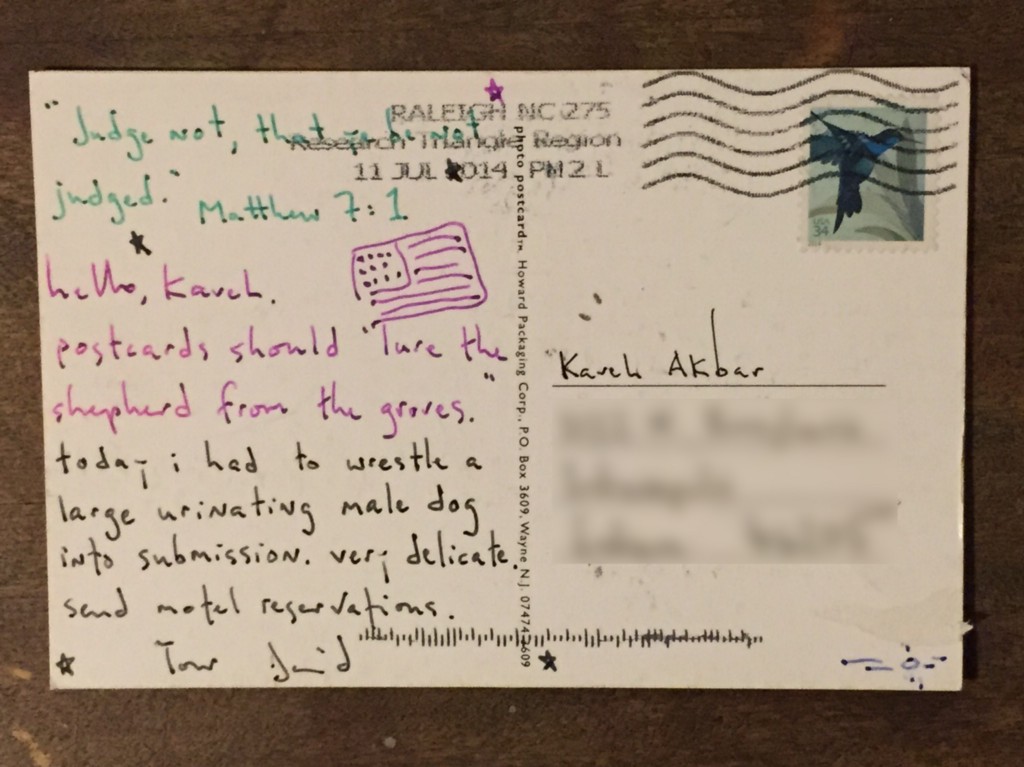

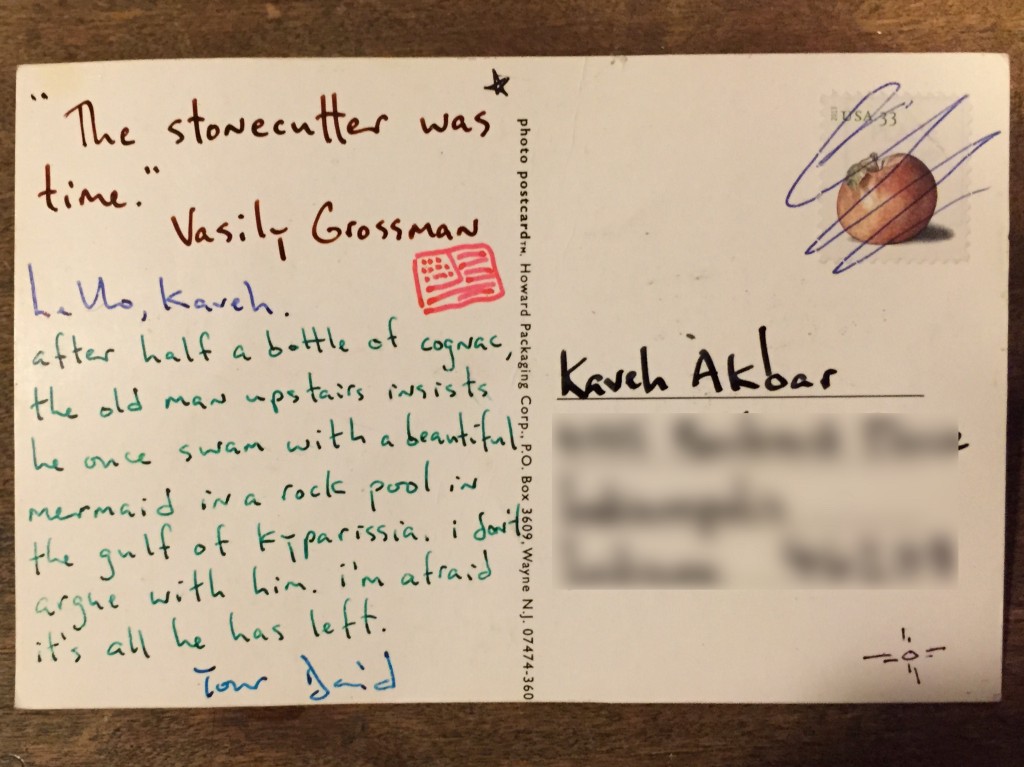

today i had to wrestle a large urinating male dog into submission. very delicate.

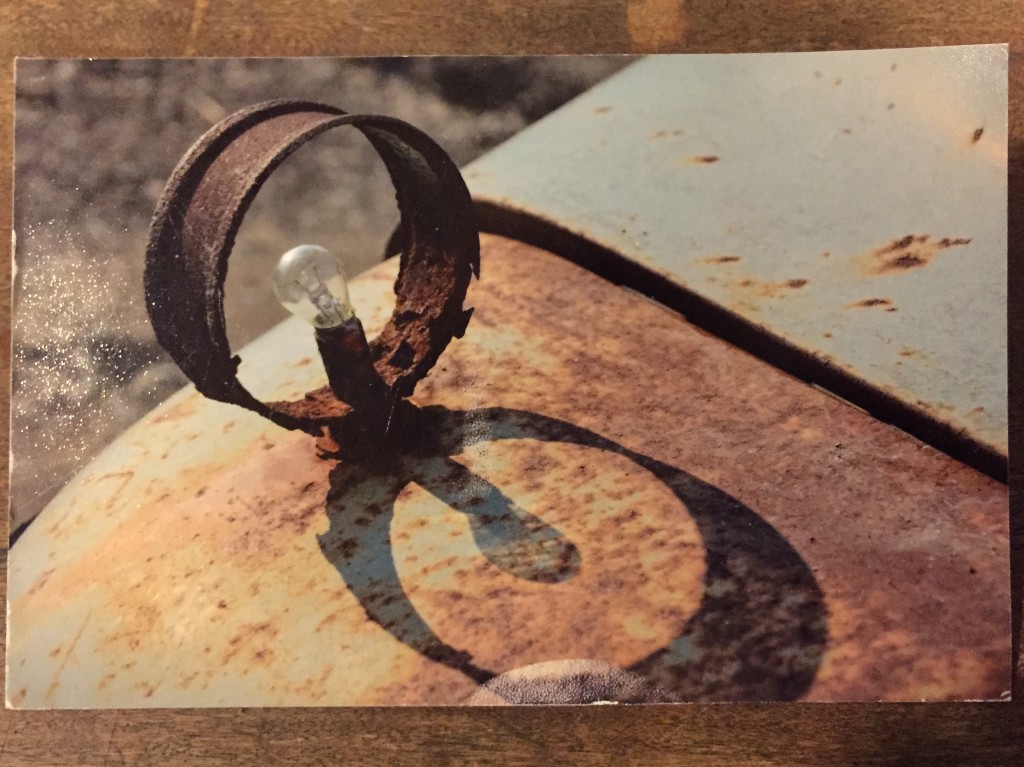

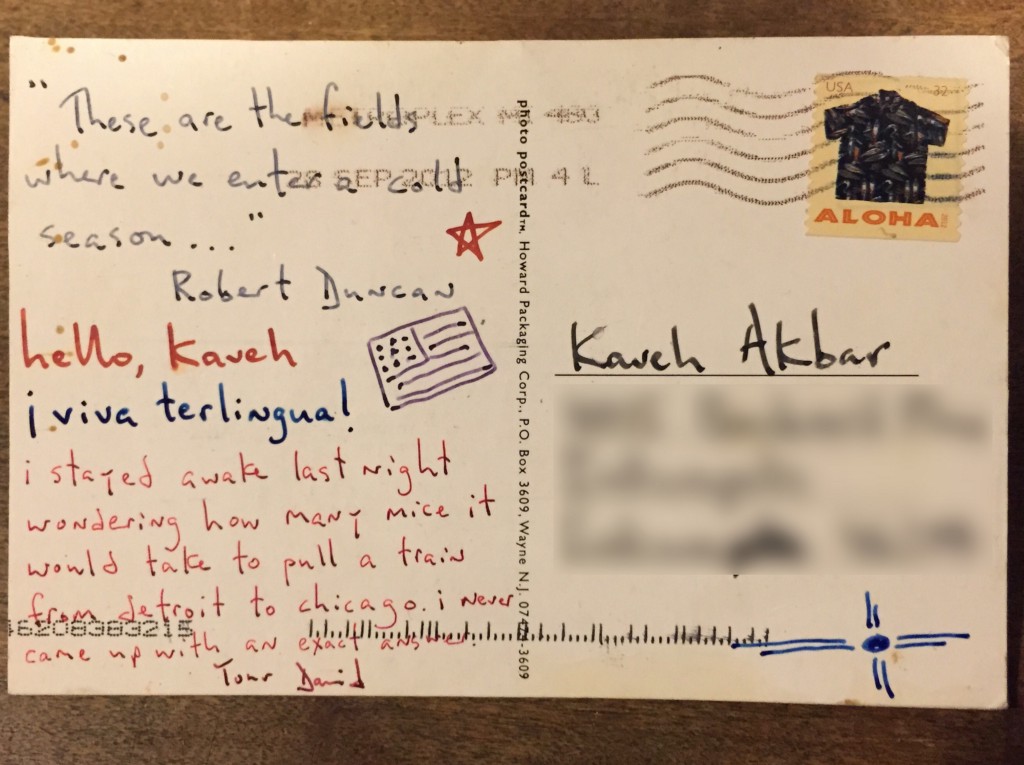

A typical David J. Thompson postcard is marked by three features. First is a photo captured from his travels around the country. These scenes deal in a sort of Midwestern gothic aesthetic — dry cornfields filled with gutted machinery, graffiti-covered liquor stores, tattered evangelical billboards, and mossed-over gravestones. Second, on the back, there is a quote from whomever David happens to be reading at the time. His favorites include André Gide (“Time passing here is innocent of hours, yet so perfect is our inoccupation that boredom becomes impossible”); Edmund Gosse (“Beauty and entertainment, we must be bold enough to insist that these come first”); and Thomas Merton (“What I find most in my whole life is illusion”). Finally, there are a few sentences from David to me about his “life.” Usually, these are charmingly fabulist. “i’m dating a woman from a nearby tuberculosis sanitarium. our romance feels rushed, but perhaps for good reason. her cough is insistent.” On another he wrote: “i’ve invested everything i own in a cornish tin mine called wheal maria. let’s hope for the best.” They’re huge in scope, frequently imagining life in a bygone era of European squalor.

This poem began its life as a postcard David sent to me (I wrote him back and insisted that he turn it into a poem).

i stayed awake last night wondering how many mice it would take to pull a train from detroit to chicago.

A few weeks ago, I wrote him a quick note to tell him I was thinking about writing an essay about his postcards for The Awl, and he wrote back, saying only: “make me rich and famous.” Barring some miracle, the odds aren’t great. There are no halls in the MoMA dedicated to postcard auteurs. But I see his work every day: in the mailbox, on my walls, in my car, tucked into books, and anywhere else I spend my time.

the old man upstairs insists he once swam with a beautiful mermaid in a rock pool in the gulf of kyparissia