Bear Stories

by Sam Worley

One afternoon in late August, I sat at a picnic table with a few family members and listened to stories about bears. This was in Upper Michigan, and it was peak season for nature in a region where nature does not require a time of year — blueberries were ripening, toads cooled themselves in the middle of every gravel road. The stories weren’t unsolicited, but the volume of them was a surprise: Over the course of a couple days, I found that everybody from my parents’ generation on up had at least one bear story, and often more.

My uncle recalled a “big bear fight” that appeared in downtown Manistique some decades ago. “It looked like something out of Ringling Brothers Circus,” he said. A bear in a cage was wheeled in and, during the day, passersby could feed it. At night, “they challenged anybody that, if they could wrestle the bear to the ground, they’d give them two hundred bucks or something.” A man named Terry Smith stepped forward. My dad picked up the thread: “Terry Smith was like, what, six-four, big, blond Swedish guy. Toughest guy in town — really the nicest guy in town too — he couldn’t even touch that bear.” I asked if the bear had been declawed; they thought it might have been. “I don’t know if the bear knew all the wrestling rules,” my uncle said.

In 1985, Ian Frazier published a piece in the New Yorker called “Bear News,” in which he suggested that the survival of the grizzlies depended on their ability to enliven our imaginations:

If enough people could imagine a world without grizzlies, and with equanimity dismiss the bears from their thoughts forever, then the bears’ actual disappearance from the physical world would probably follow soon after. I like reading newspaper stories about bears because nowadays the newspaper is such a vital part of their range. There, and in magazines and on television, too, bears fatten on certain feelings people have for wilderness, and suffer for others. They seem to try so hard to remain living things in the midst of all the fantasies people have about them.”

In Upper Michigan, the news is more modest. Grizzlies are large and dangerous; native black bears, by contrast, wander amiably through local lore. Later that night, we ate down the road at the Big Spring Inn, where a bearskin rug hangs over the bar and where black bears once lived in cages out back. Patrons bought soda bottles from a vending machine and fed their contents to the animals — either the original soda or some kind of home-made syrup. Nobody could remember.

People also watched bears at the town dump, where they dined on garbage. The civic enthusiasm that attached to dump bears — a bona fide cultural event in various parts of the country — strikes me as the charming evidence of a more innocent age, like smoking in restaurants. Until the mid-twentieth century, dump bears were a sanctioned attraction at Yellowstone, which disposed of its garbage on-site. Visitors gathered nightly for “bear shows,” sitting, according to a National Park Service history, on wooden bleachers constructed for the purpose: “An occasional park ranger, mounted on a brave horse, would often ride into view and give an educational talk about bears, while in the background, both black and grizzly bears fought over a particularly choice piece of bacon rind.” The population of grizzlies supping at the Yellowstone dumps grew from forty in 1920 to more than two hundred and fifty bears a decade later.

In 1976, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act banned the open disposal of solid waste — new landfills were to be lined to protect groundwater, and fresh trash was to be covered promptly with soil, making the whole deal less hospitable to bears. Over the ensuing decades, many existing municipal dumps were forced to close. In the Adirondacks town of Long Lake, New York, where dump bears were central to tourism, the planned closure of the dump in 1991 spurred a number of schemes to keep the bears from leaving the site, including “having everybody separate out their edible garbage and deposit it in special feeding troughs,” according to the New York Times, which conceded that “even in the middle of a dump, there is something undeniably majestic about watching the hulking bears prowl amid the hills at dusk.”

But garbage remains. Bears are not picky about where they get it. In recent years, biologists have noticed the animals getting closer and closer to where people live — the result of climate change and drought, which sends them toward inhabited areas in search of meals from campground trash and restaurant dumpsters. In northern Minnesota, a biologist named Lynn Rogers has been running a decades-long experiment in which he’s befriended, hand-fed, and monitored the behavior of a community of bears. Rogers is a proponent of “diversionary feeding”: basically, solving the problem of bears getting into campground garbage by setting out a buffet for them elsewhere. Rogers is an outlier, and his ideas are generally disdained by wildlife managers, who worry about the animals becoming too comfortable around humans, human food, and human smells. They argue that diversionary feeding might encourage bears to take the presence of a driveway trash can as an invitation into the house, for instance, and that it puts bears at greater risk of accidents like getting hit by cars. This is referred to as “nuisance” behavior in animals, though it seems unfair to fault them.

Rogers’s license to track bears by radio collar was revoked this year by the Minnesota DNR following local complaints that the bears had become, finally, a nuisance. The interspecies clashes he studies, though, will only increase as we encroach simultaneously into each other’s habitats, and the old proximities continue to dissolve. Since the closing of the dumps, not many places remain for the sorts of casual contact that used to characterize — in some small, remote parts of the country, anyway — human-bear relations.

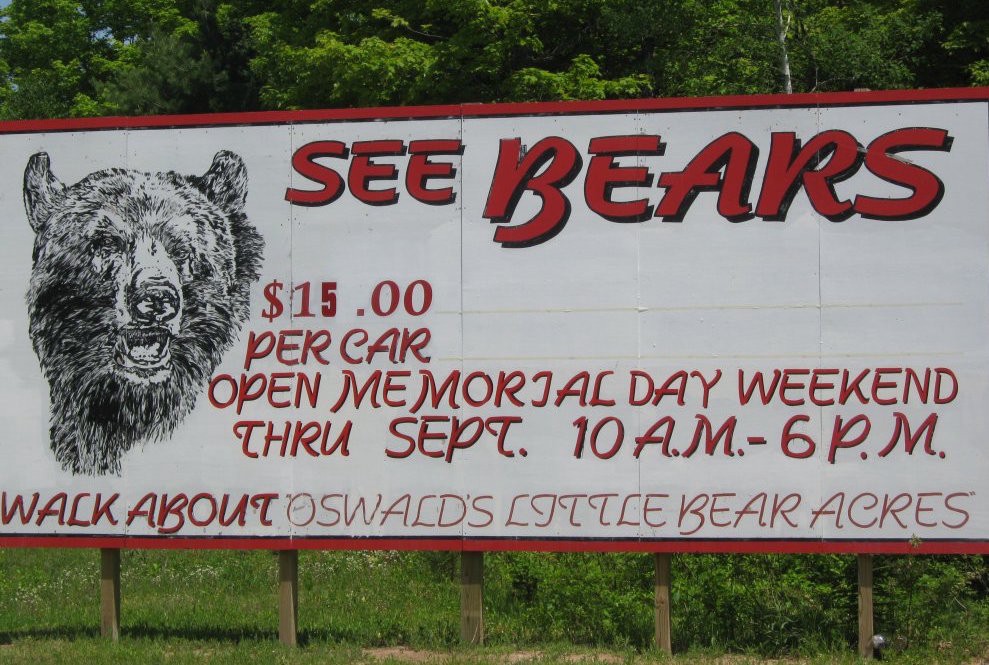

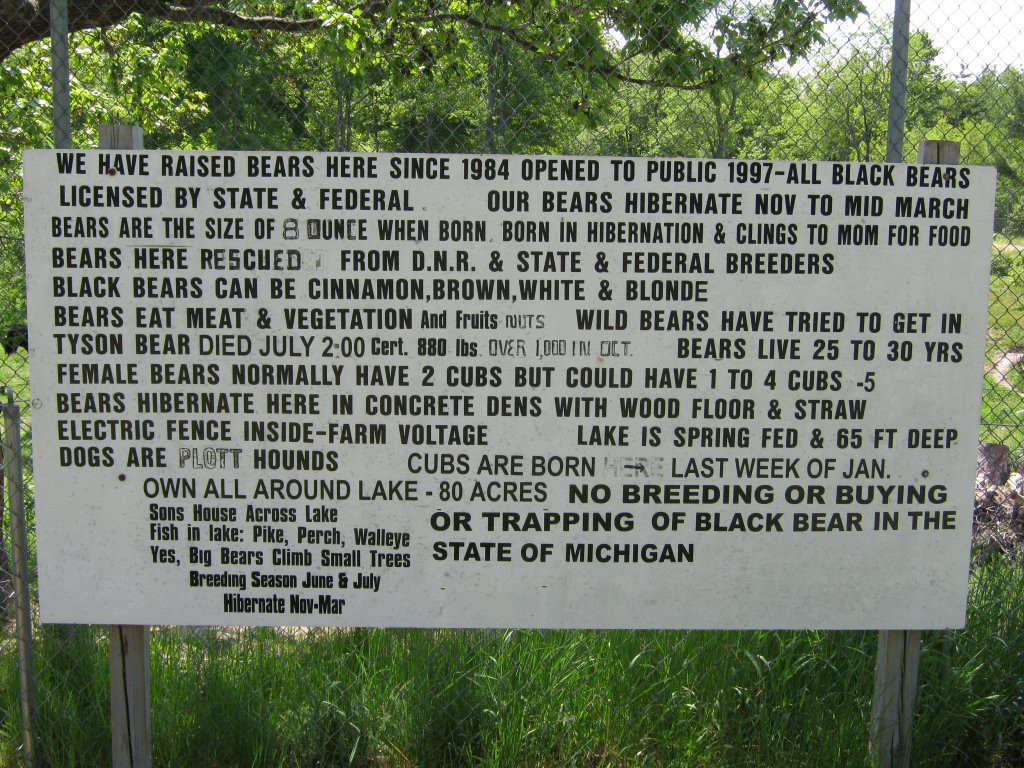

“The spirit of the bear was transformed into human flesh in the Fall of 1939 when Dean Oswald was born in a little riverside town that burned sugar beets grown in the rich, black soil of the Great Lakes,” begins the biography of Dean Oswald, the founder and proprietor of Oswald’s Bear Ranch, the self-proclaimed largest bear-only reserve in the United States, which sits within a patchwork of state forest toward the eastern end of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. In the human flesh, Oswald — who’s tall and grizzled, with a vaguely bear-like face — doesn’t say much. A retired firefighter who oversees his ursine empire from a patio chair in front of his house, which is surrounded by the bear paddocks, he talks in clipped sentences, mostly in terms of vague operational logistics. Asked what kind of traffic he gets, he said, “Oh, quite a bit,” and then added, by way of elaboration, “Lots.”

Oswald’s ranch is currently home to twenty-nine bears, most of whom are rescue animals — cubs whose mothers were hit by a car or killed in a logging accident, or abandoned by “people having them that just ain’t supposed to have them.” Oswald said that bears are like puppies, or children (“You got one, then you get two, three, and four”). He has favorites, but he’s not so effusive as to describe them in detail. They wander within four capacious habitats, segregated by age and sex, across two hundred and forty wooded, fenced-in acres.

On the sunny day in August that I visited, the bears clustered near the edge of the fence, lying around or pacing back and forth. Tourists watched and threw apple slices, which were available for purchase. A couple bears started fighting, which Oswald told me was normal; it was how Tyson, the ranch’s most famous resident, who was thought to have weighed a thousand pounds, died. “Like Andre the Giant was to the human race, Tyson was to the bears,” Oswald said. Tyson won the fight, but died of a heart attack afterward.

Oswald lived in lower Michigan until his retirement in the mid-eighties, when he moved north to fulfill what his biography calls his “lifelong dream” of owning a bear. At the same time, with bear-friendly dumps closing across the country, the dynamics of bear spectatorship were shifting. Word of Oswald’s ranch got around, and by the time he had five bears, Oswald said, people were bringing their families to see them: “I thought, well, it’d be a good idea then to put a gate up. Let ’em pay for the food.” Today, Oswald feeds the bears every day at 4:30 PM with whatever is on hand, including scraps from local restaurants and supermarkets (or, in the case of cubs, from a bottle). “And bad little boys and bad little girls,” he added, theatrically growling that last word.

In 2012, Oswald ran into trouble. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service discovered an old state law, the Large Carnivore Act, which prohibited contact between humans and, among other creatures, Oswald’s cubs — a major attraction at the ranch, where visitors were able to feed them Froot Loops by hand. “All of a sudden, they said, ‘Well, whose life can we mess up today?’” Oswald told me. The situation drew a little media coverage — the Detroit Free Press noted that the trouble was initiated by a complaint from “an attorney in town from the East Coast.” Organizations that weighed in, including animal rights groups and the Detroit Zoo, raised concerns over the effects that the contact has on both the bears and the visitors — objections that seem like an old unease, transmuted into a new one, about the boundaries of our relationships with wild animals as contact between people and bears has become less intimate and more formalized. Oswald and his antagonists reflect an adaptation: to wiser wildlife-management practices, to the physical realities that harm or displace bears, and to market forces that transmute animals into attractions. We closed the dumps; they headed for the dumpsters and we drove to the zoos.

Last year, with the help of a state senator, Oswald got the law changed, so that direct contact is now permissible between humans and bears when cubs are younger than nine month of age or weigh under ninety pounds — but now they’re fed Froot Loops with a spoon.

Photos by Julie Falk and Andrew (1, 2, 3)