Monsters in the Museum

Monsters in the Museum

by Jacob Mikanowski

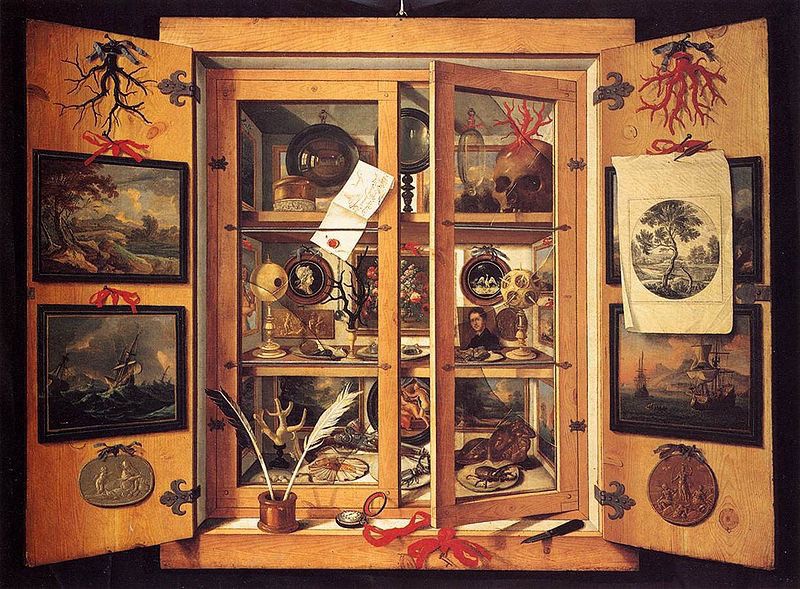

Domenico Remps, Cabinet of Curiosities, 1690s

On February 13, 1718, Peter the Great, Tsar of all the Russias, issued an edict on monsters: All monsters, animal or human, were to be requisitioned for the new museum in his new city, St. Petersburg. Peter desired anything in the realm that was marvelous — extraordinary stones, human and animal skeletons, the bones of fish and birds, old inscriptions, ancient coins, hidden artifacts, old and remarkable weapons — but he wanted monsters most of all.

Monsters, Peter believed, were not the work of the devil, but products of nature. He offered generous payment: Delivery of live specimens would fetch a hundred rubles for humans, fifteen for animals, and seven for birds. Dead ones, preserved in spirits, or, failing that, packed in double-distilled wine, were worth ten, five, and three rubles respectively. (A day laborer might expect to earn six rubles in a year). Anyone caught concealing specimens was to be fined and the sum given to the informers.

Peter’s agents fanned out across Russia to fulfill his wishes. In Siberia, pagan hunters were persuaded to turn over their idols; the grave robbers of the Irtysh Valley put down their spades to turn over the Scythian clasps and gold belt buckles they had dug up; and in rural way stations and forest hamlets, emissaries searched for strange births and deformed children.

Peter’s subjects brought him an eight-legged lamb, a three-legged baby, a two-headed baby, a two-headed calf, a baby with eyes under its nose and ears below its neck, Siamese twins joined at the chest, Siamese pigs, a baby with a fish’s tail, two dogs born to a sixty-year-old virgin, and a baby with two heads, four arms and three legs.

Peter’s agents also brought back at least three live children: Stepan, who lacked genitals; Foma, who was born with ectrodactyly; and Iakov, an intersexed blacksmith. They had come far to be put on display in Peter’s museum, but being on view wasn’t all they were expected to do: After hours, they swept and cleaned and kept the fireplace fed. As Russians, they were Peter’s subjects, and subjects were expected to serve.

When Peter took the throne, Russia was unlike the rest of Europe. Science and philosophy, as practiced by Newton and Descartes, were unknown; no one knew Latin; upper class women weren’t allowed to leave the home; and the few foreigners in the country were restricted in their movements and confined to special “Western” quarters of certain towns. Religion reinforced this sense of difference. The Russian Orthodox Church stood as a bulwark against foreign influence from godless Catholics and heathen Protestants — and the church was more progressive than many of its believers, some of whom cut off their fingers or fled into the forest, rather than go along with a change in the liturgy.

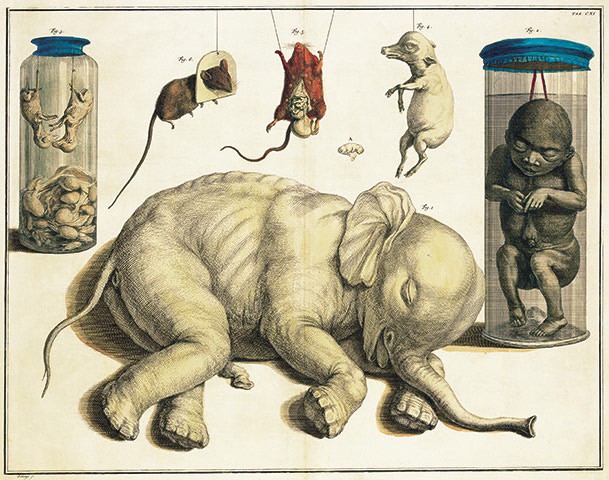

Cabinet of Natural Curiosities, Albertus Seba, 1731

Soon after assuming sole power in 1696, Peter passed a series of laws aimed at bringing Russia closer to the modern, Western fashions he had seen on trips abroad. He reformed the calendar, the army, the way people dressed and even how they ate soup (no more slurping). The museum was part of that ambition. Its exhibits–unusual objects, inventions, and works of art — were designed to inspire his countrymen to broaden their horizons and enlighten their minds. Leibniz, the German philosopher, who advised Peter on the meaning and purpose of the collection, urged that the displays should “serve not only as objects of general curiosity, but also as a means to the perfection of the arts and sciences.”

But Peter’s subjects didn’t necessarily want to be modernized. The new laws struck them as godless and obscene. Many began to doubt that Peter was really their tsar. Preternaturally tall, with a small head perched atop an unusually long torso, afflicted with a variety of tics and tremors and subject to sudden changes of mood, some said Peter resembled a monster himself. Like foreigners, he smoked tobacco and wore frocks; rumors began to go around that he was an impostor, switched at birth with a German baby or that he was a Swedish barber in disguise. Through a change in the calendar, some argued he stole eight years from God; he was the Antichrist, his followers were devils, and when he sat on the throne, smoke came out of his mouth.

Peter met the skepticism with contempt. While assembling his collection of curiosities, Peter wrote to Leibniz to complain about his fellow Russians: “If I wished to send you humans who are monsters not on account of the deformity of their bodies but because of their freakish manners, you would not have space to put them all.”

This is what Peter knew: that anything can happen to anyone, at any time. From the start, his life obeyed the capricious logic of a fairytale. He was raised in a gloomy castle, haunted by the absence of his dead father. When he was young, he was dominated by a wicked half-sister and passed over in favor of a lesser brother. When he was ten, the royal guards rebelled; they burst into the palace and dragged away his uncle and hacked him to pieces. Peter and his brother were brought out onto the palace balcony to calm the crowd. Their father’s best friend went with them and was pitched from the balcony by the guards and impaled on soldiers’ pikes below.

The knowledge that even the emperor was a subject of chance opened Peter up to other identities, other selves. Throughout his life, he collected aliases, nicknames and disguises. At different times he passed himself off as a common soldier, a Dutch peasant, a drummer, an admiral, and a shipwright’s apprentice. When he travelled abroad he hid behind the name Peter Mihailov — Russian for John Doe — and made people in foreign courts pretend they didn’t know who he was, even though they did. At home, outside Moscow, he had special barracks built so he could sleep with his troops and direct pretend battles around the clock. He liked explosions and fireworks; singing and drumming; globes and telescopes; setting fires and fighting fires. He especially liked making things: a bench, an armchair and a rowboat out of wood, a snuff box out of rhinoceros horn, and a chandelier out of bone.

In Russia, as in medieval Europe, carnival was the annual event in which the low became high and the high became low; the world opened up — to different bodies, different genders, and different sexualities. In some ways, Peter’s whole reign was a carnival: He surrounded himself with the short to seem tall, the foreign to seem Russian, the humble to seem eminent and the strange to seem normal. He liked to have his favorite dog, Lizetka, sign his letters with a paw print.

Early in Peter’s tenure, he inaugurated a parallel court with a parallel clergy, called the All-Drunken, All-Jesting Assembly, which was ruled over by a pretend tsar — Prince Fedor Rodomanovsky, the head of Peter’s secret police, who happened to own a bear trained to serve his guests vodka — and a pretend pope. Though the Assembly mocked and rituals of power — and drank, a lot — both exercised genuine authority over Peter, who, in that context, was just an ordinary citizen; he wrote letters to Rodomanovsky, reporting on his activities, boasting about his advancement through various ranks of the army and navy, and asking for approval in important matters. To Peter, true power meant the freedom to become anyone he wanted.

The museum Peter built in St. Petersburg was meant to bring science to a backward country. Instead, it became a reflection of the corridors of Peter’s restless mind. He took great care and spent an exorbitant sum of money putting it together. On his trips abroad, in between lessons in shipbuilding and parliamentary procedure (while in England, he watched the House of Commons conduct its business from the roof of a neighboring building), he purchased unusual items for his collection. In Amsterdam, he visited the house of Maria Sibylla Merian, the celebrated naturalist and scientific illustrator, and admired the many butterflies and insects she had gathered on her travels to Suriname. From the apothecary and curiosity merchant Albertus Seba, he bought a vast collection of zoological specimens and biological rarities, including a baby elephant and a many-headed dragon, though he missed out on a pair of conjoined baby antelopes, which had been promised to someone else.

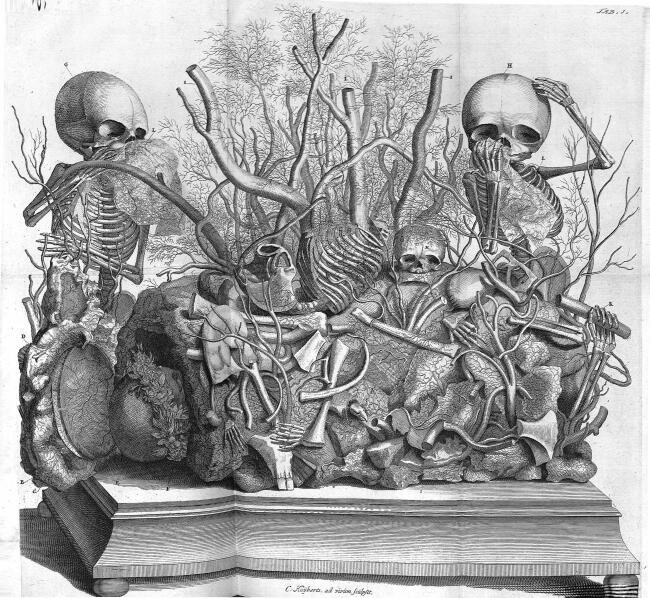

Baby Head with Turkish Hat, Frederik Ruysch, ca 1720

Peter’s favorite supplier of curiosities was a man named Frederick Ruysch, a master embalmer and the greatest taxidermist of his age, who had mastered a secret technique for preserving dead bodies and making them look as if they were still alive. He injected their veins with a special mixture of talc, tallow, wax, cinnabar and oil of lavender. One of his contemporaries observed, “All his injected carcasses glow with striking lustre and bloom of youth; they appear like so many persons fast asleep; and their pliant limbs pronounce them ready to walk.” Sometimes Ruysch took his preserved specimens and arranged them in miniature scenes. His favorite subjects for these displays were the tiny skeletons of fetuses. He liked to pose them, fully articulated, in miniature gardens, whose every element was fashioned out of various pieces of preserved organs. In Ruysch’s hands, blood vessels become corals, gallstones sponges, and the minuscule skeletons explorers on the bottom of the sea.

Cornelius Huyberts, Anatomical Still Life by Frederik Ruysch

Ruysch’s favorite subject was lamentation. In one scene, a skeleton plays a violin, made out of diseased bone, with a bow of dried artery. “Ah fate, bitter fate!” he sings, while another skeleton conducts music with a baton set with kidney stones. A third skeleton, wearing a belt of sheep intestine, grasps a spear made of a hardened vas deferens. In others, the skeletons hold mayflies or scythes.

In another tableau, two skeletons standing on a mountain of kidney stones, surrounded by miniature trees made out of the branching fronds of hardened arteries, weep into handkerchiefs made from abdominal membranes. The message these tiny figures convey is all the same: that their first hour was also their last. Ruysch took special care in preparing the membranes to make to make their delicate blood vessels look like embroidery. They reminded him of Psalm 139: “My substance was not hid from thee, when I was made in secret, and curiously wrought in the lowest parts of the earth.”

When Peter saw the collection, he was reputed to have been so moved “that he tenderly kiss’d a little infant, which sparkled with all the graces of real life and seem’d to smile upon him.” Impressed beyond words by the life-like infants and tiny skeletons crying into their membranous handkerchiefs, Peter bought the whole lot.

It’s difficult to find out much about the lives of the monsters in Peter’s museum, who were illiterate, and lived in extreme poverty. They were made to display their deformities and perform for visitors. Foma, the boy from Siberia, amused guests by picking up money off the floor with his fused fingers. When he died, his body was dissected and his organs were preserved for later study. Although not everyone viewed the living exhibits as fully human, at one point some of the savants at the museum took a scientific interest in their origin. They interviewed one of the children’s fathers to learn more about the circumstances of their birth: “no, there are no other children like our son in the area”; “no, my wife didn’t have any complications during labor”; “no, she didn’t see a convict when she was pregnant.”

The father’s answers speak to a certain weariness. So do the words of the monsters themselves. They complained of cold and hunger, and petitioned for extra clothes and back wages. Some of them tried to run away, and one, an intersexed person, successfully escaped. One visitor to the museum, describing the condition of Stepan, the boy with no genitals, conveys their situation best: “This man, they say, is from Siberia and his parents are simple folk. He would gladly give a hundred rubles or more, if only he could regain his freedom and return to his homeland, from which his parents were forced to send him by the Imperial decree.” The monsters did not think much of the honor of being in Russia’s premier museum.

Wax figure of Peter the Great, Carlo Rastrelli

Stepan never got his wish, and he ended his life as an exhibit in the Academy. In a way, so did Peter. After the Tsar’s death, his successors placed a life-size a wax effigy in the museum. One room away from the bones of Peter’s giant, near to the preserved fetuses he brought back from Holland, it sits there still, wearing the worn boots that spoke to his great thrift and the stockings that he knitted himself, his favorite dog Lizekta at his feet.

Inset images: Foma Ignatiev, drawing from the 1830s; Cornelius Huyberts, Anatomical Still Life by Frederik Ruysch, from Opera Omnia, Amsterdam, 1720.