A Prison for the Dead

by Chris Arnade

Millie, the last time I saw her

When Millie died last year, her foster mother was in a nursing home and her pimp was in jail. Nobody came to collect her body, so the city buried her where it has interred a million other unclaimed bodies: in a massive trench on an inaccessible, desolate shard of land in Long Island Sound called Hart Island.

Millie had spent New Year’s Eve walking the track — the empty part of Hunts Point in the Bronx, where the older prostitutes, who liked the quiet, worked. She stayed out until daybreak, alternating between getting into cars and walking up the hill to buy drugs with the money, then slept most of New Year’s Day. The next evening, she collapsed in the Tub and Tumble Laundromat, a place she often wound up when she didn’t have anywhere else to go. Before falling, she apologized to Ana, the manager and her friend, saying she was feeling ill. She was taken by ambulance to Lincoln Hospital.

She had no identification. She kept it, along with other important papers — mostly pink slips from the police — in an old Ziploc bag that was stashed in a small fence post on the empty street she worked. Nameless, she was admitted as a Jane Doe.

Millie with papers

A few days later, she died and her body was moved to the basement morgue and tagged BX97 — the Bronx’s ninety-seventh death in 2013.

Nobody came looking for her. Her thirteen siblings, cobbled together from various foster homes, were acclimated to her disappearing for long stretches of time, after which she would re-materialize, just released from jail or looking for a home to detox in. Her friends from the streets, the ones she called her sister or her aunt or her mother, assumed she had gone into rehab or jail. A few feared she had died — she had a massive abscess the length of her arm that worried them — but they didn’t have phones or computers to look for her.

Two months after she died, Millie was buried by inmates from Rikers, another body piled on a million others in New York City’s public cemetery, the last stop for those who die alone or destitute.

On the streets, little is certain. Hart Island magnifies that uncertainty, adding one more thing to fear about death — a place where you are buried in a trench that nobody can visit. Millie’s friend Pepsi talks often about it. “I don’t want to be buried like a stray dog,” she told me. “I hope to God and pray that I don’t get treated like that. I want the decency to be buried by those who love me.”

It’s little coincidence that Hart Island feels like a prison for the dead: It is run by the Department of Correction. Everything about it is intentionally ambiguous: It is illegal to photograph (images come from photographers flying in rented helicopters or using telephoto lenses in kayaks); the names and stories of the people buried there are only now being made available to the public; and nobody can visit burial sites.

Some take precautions to avoid winding up there. “I had gotten ten bags of great shit. I knew it was all going in me and that it could end that night,” Pepsi said. “So I wrote my father’s phone number in marker on my stomach before shooting up for the paramedics to see.”

Jackie

In August, Jackie, who also worked for Millie’s pimp, went into a coma after shooting a bundle of really good dope in a crack house. An ambulance was called and Jackie was taken to Lincoln Hospital. She was twenty-four years old when she died. Nobody knew her real name; she had spent her last four years in Hunts Point, shifting between a shelter and the streets, where she was just Jackie. Jackie with lupus.

Without the information needed to track or claim her body, Jackie would’ve lay unclaimed, eventually tagged BX #,###. After two weeks in the hospital morgue, if still unclaimed, a body is shipped to the City Medical Examiner’s office where an autopsy determines cause of death. For Millie, her death was due to “Bacterial Endocarditis of tricuspid valve due to intravenous drug abuse.”

If still unclaimed after roughly two months, the body is moved by a refrigeration trunk, filled with other bodies, to City Island in the Bronx, then loaded onto a ferry for the half-mile ride to Hart Island.

On Hart Island, inmates, bussed over each morning from Rikers, place the bodies in wooden boxes that have been made by other inmates. The boxes are lowered into a large, standardized trench, seventy feet long, twenty feet wide and six feet deep, dug by backhoes. When no more boxes can fit, the trench is covered, and a new one is dug to accommodate the next set of bodies. This process has been ongoing, more or less uninterrupted, since 1868.

You can, if you are very determined and organized, visit a sliver of Hart Island that is unused for burials. Every third Thursday of the month, the ferry normally used to transport remains brings passengers for closure visits. These small visits are a recent change, due to the twenty-year effort of one artist, Melinda Hunt, and her non-profit, the Hart Island Project, whose goal is to bring awareness, transparency, and a measure of dignity to the process of dying poor in New York.

Ferry to Hart Island

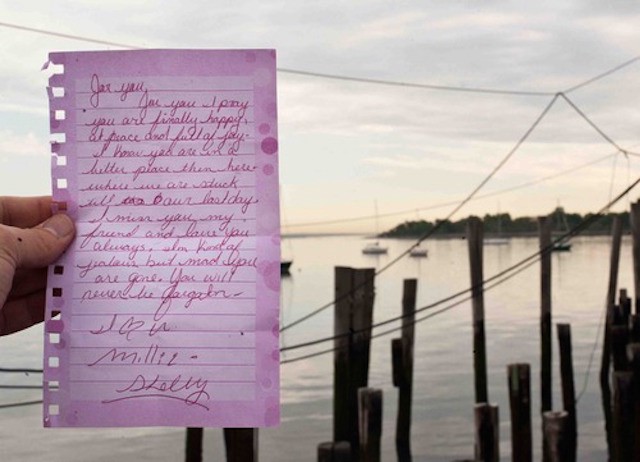

I offered to bring Millie’s friends, but none had the proper photo ID or were comfortable presenting it to corrections officers. They did give me a few items to bring: A letter, a small bottle of water from the open hydrant Millie used to cut her heroin with, and a half dollar. “What is a better memorial to a street whore than a ripped dollar bill?”

The letter read:

For you I pray you are finally happy, at peace and full of joy. I know you are in a better place then here where we are stuck till our last day. I miss you my friend and love you always. I’m kind of jealous but mad you are gone. You will never be forgotten.

I love you Millie

Shelly

On the island, you can walk fifteen yards from the ferry landing to a small fenced-in plot with an awkward looking gazebo and a single ceremonial tombstone, inscribed with scripture that is dedicated to the collective dead. Small dirt roads, shielded by Department of Correction vans, run off from the ferry landing, the view beyond blocked by rows of trees and decaying buildings — the remains of old institutions for the poor and sick.

I read the letter to Millie, tore it up, and sprinkled it and the water around the fenced-in plot. Then I sat on the gazebo and listened to the sounds of gunfire echoing continuously from the the city’s police training range, just across the water.

Hart Island seen from the Bronx