No Offense to Laura Ingalls Wilder

I don’t remember the time before I could read. Reading has always been an integral part of who I am, how I define myself, and how I structure my days. When work or life interferes to the point that I don’t get hours of reading squeezed in every week, I get antsy, and feel depressed and confused. It’s how I recharge my batteries and refresh myself.

And then I had a baby. Given an hour alone these days, it turns out, I’d much rather lay on my bed or stare at a wall, just being, than pick up a book.

In the early days of Zelda-life, I hadn’t realized that yet, and I felt frantic to read anything. We spent twenty-four hours a day together, and she was mostly just laying around, swaddled up in some container — a basket, a bassinet, her crib. It didn’t, at first, feel natural to me to have a one-sided conversation with my daughter. That passed very quickly, but before then, I filled our time together with reading. Sometimes I read the paper, sometimes The New Yorker (though sadly, she didn’t seem to enjoy it). Then I started buying her books I had cherished as a child, and we read them together.

The third book I read to Zelda was Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (I’ll get to the first two in a second). Then The Wizard of Oz. Then The Little Prince, The Canterbury Tales (boy did she love them!), Me & Fat Glenda, and then Island of the Blue Dolphins. Then we chomped through The Phantom Tollbooth, and The Call of the Wild. Then we branched out from children’s literature and read My Struggle: Book One. Just kidding, I wouldn’t do that to her. That one I read alone.

Alone. Reading is largely a solitary activity, but reading aloud to someone is very different. During a series of long car trips years ago I read my favorite book — Jane Eyre — aloud to my husband. It took hours and hours, and I remember noticing how different this book, which I’ve read probably a dozen times, seemed when reading it together with someone. So Zelda has changed reading into a social activity, one which I really cherished in the first six months, before she could move around, when she was patient and happy just to listen to the sound of my voice.

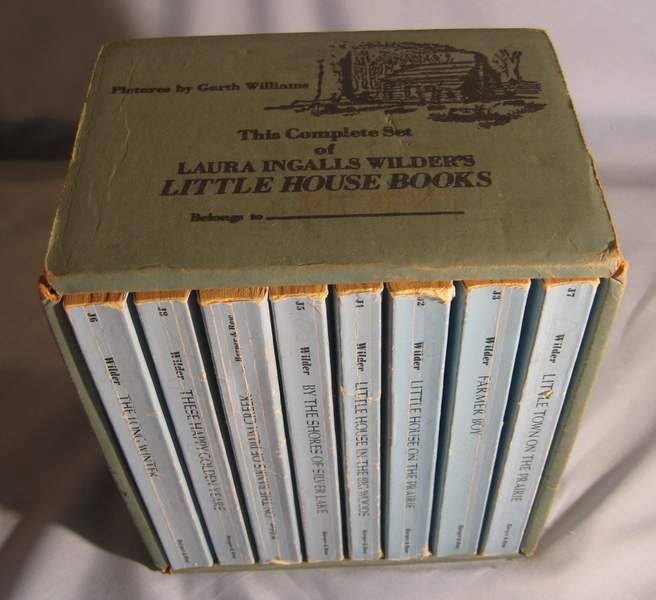

But reading a book aloud to a baby, even one who doesn’t understand a word of what you’re saying, certainly changes your perception of the book. The first two books I read to Zelda were childhood favorites: Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House in the Big Woods and Little House on the Prairie. When I was eight or nine, I inhaled these books, compelled to begin reading them simply because the author and I shared a first name. I checked them out of the library one-by-one, slowly becoming obsessed with the idea of a pioneering lifestyle, so foreign and unknown to me. Then I asked for, and received, a boxed set of the books of my own.

But I hadn’t read the books since I was in middle school when I started to read them to Zelda, and though my memory of them was really quite solid — a testament to the vibrancy of the writing — I looked at these books with new eyes, and I didn’t like what I saw. It started off with little things. Pa skins a deer, sets some bear traps, and makes a ball for Laura and her sisters from the bladder of a pig. “It doesn’t hurt him, Laura,” Pa tells a whopper of a lie about butchering a pig on page thirteen. Of course, the pioneer life was all about these harsh realities, and I’m sure it’s at least partly what drew me to the books as a child. We don’t read to see an exact reflection of our own lives, or lives as we think they should be, after all.

But then Pa sings a song on page ninety-nine. Here are its lyrics (imagine that Pa is also fiddling):

There was an old darkey

And his name was Uncle Ned,

And he died long ago, long ago.

There was no wool on the top of his head,

In the place where the wool ought to grow.

There is a second verse but the first is enough, right? Imagine me reading these lyrics aloud to my daughter in her crib, just two weeks old. I didn’t. I started, then saw what the words said, and skipped right over the whole song. I imagined her, eight or nine years old, reading the words. Would she even know what it meant? Would she need an explanation? Would she ask me about it? “Oh you know, they were preeeettty racist back then, so sometimes people called black people ‘darkeys’ but not anymore. Great book though, right?” We kept going, even though at this point the varnish had started to wear thin on my childhood memories.

Nothing prepared me for Little House on the Prairie, formerly my favorite book of the series, which details the Ingalls family’s move from Wisconsin to Kansas in 1869, which at the time was still Indian Territory. This book is brimming with casual racism about Native Americans. They are described as “savages” and “wild,” and both Ma and the family dog dislike them openly. “Why don’t you like Indians, Ma?” Laura asks on page forty-six. “I just don’t like them; and don’t lick your fingers, Laura,” Ma said.

The Ingalls family are Manifest Destiny personified. The Osage Indians they encounter are a brooding pack of inconvenience, and just one Native American gets the role of the “noble savage” — a chief who supports the settlers against his own people to keep peace. Pa implies the worst about them (on page one hundred and forty-six) when he tells Laura and her sister that if given the opportunity, the Indians would certainly off the family pooch, Jack, but “that’s not all” he says. “You girls remember this: You do as you’re told, no matter what happens.”

I didn’t remember any of this from my childhood reading. I probably glossed right on over it in favor of the juicy details of skinning a rabbit or how Pa builds the cabin. The good stuff.

Zelda and I finished the book, but we decided (well, I did) not to read any further installments. These books are a fascinating and incredibly flawed version of a series of events which actually occurred, remembered through the eyes of a small child, and written in the nineteen thirties. As an adult, I can make sense of what I’m reading. I have context. I know history. And the events as described make me terrifically sad. I don’t think that a child of eight or nine can make sense of these books without a lot of context, a lot of explanation, and honestly, I’m just not sure they’re worth it. I’m not sure that their literary value is so high that I can overlook what I see as grave and deeply integral flaws. I think that they are outdated and old, and sometimes things just need to have an expiration date; they’re like curdled milk to me. I’ve thrown them into the garbage with the Velveteen Rabbit, which I have decided not to read to Zelda either, because the name Skin Horse is creepy and why bother worrying her about When Toys Become Real? Reality is tough enough without thinking about that. I put them into the garbage with the many other books which reflect a largely white, very Christian ideal conception of the world, because that conception is both innately flawed and also outdated.

That’s not to say that I think certain books should be censored or kept out of schools, or that they shouldn’t be read. (I don’t.) That’s also not to say that I think she is or will be “too young” to read them and understand. If I have learned anything in parenting it’s that babies and children pick up on things much faster than adults, and that she is capable of understanding so much, so easily. But parenting is all about making small judgements. When Zelda is seven or eight and can read, she will be allowed to read anything her heart desires. If she wants to read Laura Ingalls Wilder, I’ll explain to her how racist they are, and how flawed their vision of the world is, was, and always will be. Until then, we’re going to try to read something better. Like A Wizard of Earthsea.

THE PARENT RAP is an endearing new column about the fucked up and cruel world of parenting.

Laura June is a writer and a very cool mom. She is also the author of “The Vampire Diaries.”