Every Email Is a Ghost Story

by Reyhan Harmanci

You think you know someone. Then you find your college email account.

Towards the end of a dinner party with four old friends, when the wine gave way to whiskey, we began reminiscing. The subject turned to how much we didn’t remember from those years and an alarming fact surfaced: Someone at the table had transferred her college email to Gmail. With a few taps, she surfaced a long-suppressed history. “What kind of maniacal mind would do that?” Jenny asked, frowning. Another diner attempted to trace the email archive’s journey: It had gone from a turn-of-the-century system called Telnet (think blue background, orange letters, all DOS-style text) to the Wesleyan University web browser to Yahoo! Mail to, finally, Google. What kind of maniacal mind, indeed.

It turns out that ancient emails make for a great party trick. Claire chronicled her time spent studying in an email entitled “barf”:

“i am working and writing and yet the paper refuses to get to 1000 words. i hate it! where are you working today? there is a hurricane outside and i keep farting.

yuck.

There was a dramatic reading of a note that I wrote, entitled “destinys child.” In it, I expressed a deep desire to acquire and consume alcohol:

at the rate i’m going, i will be in the hospital before the end of the week, so i’ll have to be wheeled downstairs to the ballroom in a full-body cast for the semiformal. I’ll have to pay someone to hold my drink next to my moveable cot since even being in traction couldn’t stop me from drinking.

Poetry.

The next day, though, I woke up unnerved and dimly remembered getting badgered by Wesleyan after I graduated in 2001, asking me to do something to save the messages after they were transferred onto a web-based system. I typed in “email.wesleyan.edu” and my old username, just to see what would happen.

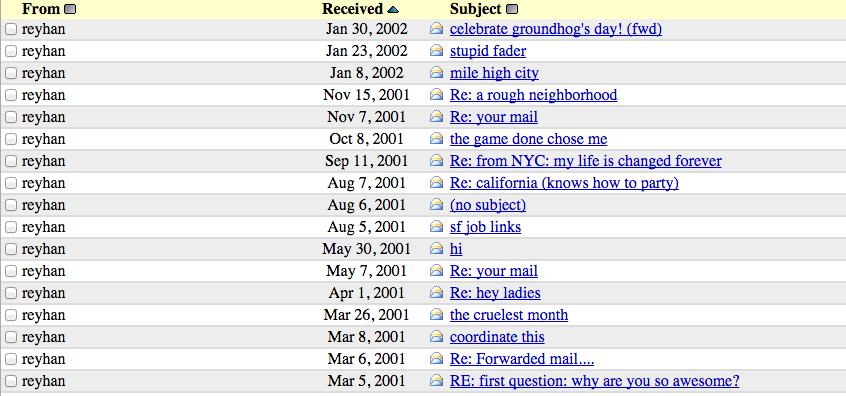

It opened up with my first guess at a password. Over four thousand emails — including sent mail, drafts, “_pine_interrupted_mail,” something called “dead letter” and another folder called “postponed_msgs” — stared at me. Who were these people? Who was I?

hi guys. i wwant to apologiz

I must have spent half of college ducking into a computer lab, sending group emails. The bulk of the messages were to my friends on campus, who were locked up in computer labs or waiting elsewhere, patiently, for the static of a dial-up modem to clear. (It was probably possible to email my parents but I couldn’t find any messages to them in my account.) One thing that never occurred to us — or at least to me — was whether those messages were being stored. But of course they were.

The truth is that we are surrounded by digital ghosts, easily conjured. The notion that people, especially younger people, are vulnerable to bad digital decision-making has risen to the level of public policy — Europe recently enacted a “right to be forgotten” law that has Google excising unpleasant links from individual search histories. But the idea that some indeterminate past self can fly out of nowhere is disconcerting beyond, say, a prospective employer seeing an embarrassing picture. Self-respect, to paraphrase Joan Didion, isn’t about the public face of things — it concerns a “private reconciliation.” Locked in my college email box were drafts and funny notes but also a trove of strange saved messages. They were emails that I had written and for some reason — sentimentality, pride — felt compelled to save. Most were unsent. They were, I think, an attempt at love letters.

One of the oldest saved messages was a personality survey that had gone around campus, where you get someone who knows you to fill out questions about your life. I sent it to an ex-boyfriend and then saved his reply. “Ok, I took the time out to go through this questionnaire. I hope we aren’t enemies now,” he had written, blithe to my obvious desire for attention. Well, not completely blithe: “Again, in no way does this summarize the many ways in which I see you and think about you, but I also know that you really love to get email responses.” In my unsent folder, another kind of horror awaited. Think, say, two dozen emails of varying degrees of forced casual responses to… god only knows what. What the hell was I so upset about? The end of a paragraph about classes came one typical zinger: “By the way, did I ever mention that I harbor lots of anger towards you that I never got around to expressing?”

Buried in another folder, labeled “eclectic,” sat another surprise: notes from Chuck, this mountain of a guy and a Wesleyan legend who graduated a few years before me. He oddly befriended me when I was a freshman and he was a junior. When I first met him, he had taken a semester off but lived on campus, working at WesWings (even though he was vegan) while intermittently working on his dissertation on death metal music. The week before I graduated college, and was set to move in with him in a house in Boston, Chuck died unexpectedly in his sleep.

To this day, his death just doesn’t make sense. But the saved messages reminded me of all the tiny, dumb moments of our friendship that I had forgotten. The oldest email I have from him is dated 2:43 a.m., 1999, with the subject line “no offense”. Whatever he had said, I can’t remember, it seems to be some joke about my sexual prowess, but his misspelled apology is so sweet:

i didn;t mean to offend you tonight. i love you one million percent and the alst thing i want is for you to think that i think that you won;t ever get anyl.

I love the idea of Chuck earnestly apologizing for making a joke about me not getting any. If there was a redeeming aspect to all of this, it was the pleasure in being reminded of not only my past idiot selves but all my friends’ past idiot selves. We all used obtuse greetings (“hi pork,” “Yim Yimmer,” “kwan”) and wrote disastrous subject lines (“the game done chose me”). College was a haze of forward chains and personality quizzes and e-greeting cards and long, long letters during breaks as short as a weekend. There was no mistake worth making that couldn’t be sent to at least ten other people.

We weren’t reinventing the wheel: a few years before us, people would have sent actual letters and spent hours on the phone chronicling their fuck-ups. A few years later, all the action moved to a few weird apps. But we had email. No one older than us had more experience with technology than we did, and we had no concept that these messages were anything but ephemera. Email, at this point in our lives and its life, was still for fun, not just work.

So we made the most of it. The following is a message from a friend, forwarded to me twice:

And I still have no idea where my cell phone is. For some reason, I’m scared that the words “if you make out with me, I’ll give you my cell phone” came out of my mouth last night. I know I definitely thought that. Oh god. Did I make out with someone in exchange for my cell phone.

The cell phone was never found.

Photo by Alexander Baxevanis