The Drivers Must Roll

The Drivers Must Roll

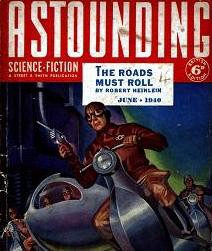

Here is some totally unhelpful but still fascinating background decoration for Uber’s incredibly rapid recruitment, containment and domination of its drivers, who, if they work in New York, just found out that their recently and suddenly reduced rates are now permanent, despite protests. It’s a passage from Robert Heinlein’s 1940 short story, “The Roads Must Roll,” in which cars have been replaced by enormous conveyors operated by a largely invisible network of technicians:

The speaker pressed his advantage, his words tumbling out in a rasping torrent. He leaned toward the crowd, his eyes picking out individuals at whom to fling his words. “What makes business? The roads! How do they move the food they eat? The roads! How do they get to work? The roads! How do they get home to their wives? The roads!” He paused for effect, then lowered his voice. “Where would the public be if you boys didn’t keep them roads rolling? Behind the eight ball, and everybody knows it. But do they appreciate it? Pfui! Did we ask for too much? Were our demands unreasonable? ‘The right to resign whenever we want to.’ Every working stiff in any other job has that. ‘The same Pay as the engineers.’ Why not? Who are the real engineers around here? D’yuh have to be a cadet in a funny little hat before you can learn to wipe a bearing, or jack down a rotor? Who earns his keep: The gentlemen in the control offices, or the boys down inside? What else do we ask? “The right to elect our own engineers.’ Why the hell not? Who’s competent to pick engineers? The technicians — or some damn dumb examining board that’s never been down inside, and couldn’t tell a rotor bearing from a field coil?”

He changed his pace with natural art, and lowered his voice still further. “I tell you, brother, it’s time we quit fiddlin’ around with petitions to the Transport Commission, and use a little direct action. Let ’em yammer about democracy; that’s a lot of eyewash — we’ve got the power, and we’re the men that count!”

It’s a strange story with some great lines:

[Automobiles] contained the seeds of their own destruction. Seventy million steel juggernauts, operated by imperfect human beings at high speed, are more destructive than war.

It’s also a work of adventurous and pulpy speculative fiction, in which the world is powered by a “Sun-power screen” and road workers the country over have been seduced by a radical “Functionalist” philosophy that says — and this is all we ever really get to find out about it — that it is “right and proper for a man to exercise over his fellows whatever power was inherent in his function.”

In the story, the power “inherent” in the road-workers’ function is dangerously great, in part because of the design of the road and in part because they are formally organized; in real life, in our actual budding dystopia, the prospect of an effective labor movement for Uber drivers does not seem plausible at all.

While there was talk of drivers unionizing at Friday’s meeting, the protest appears to be struggling to reach and mobilize a critical mass of Uber drivers. Much of the organization appears to be haphazard, with drivers relying on personal networks and cold-calling.

“Text every driver you know,” Abdoulrahime Diallo, one of the organizers, instructed the protesters. “It’s worth the investment, tell them to stand with us.”

Uber, which has openly professed its intention to scale as quickly and in as many infrastructural directions as possible, did not seem bothered by a series of protests in the city, suggesting that it would consult its internal data to decide whether or not to make the surprise fare decrease permanent. The data said whatever Uber expected or wanted it to say, and so it’s sticking to its plans. Everything else is noise. Noise is inefficiency. Its drivers are to have no power, inherent or otherwise.

It’s literally and politically of a very different time; unions are increasingly treated like a spent sci-fi trope, and the equivalent workers today wouldn’t be asking for better terms so much as any reliable terms at all, or the right to secure them. Also, I don’t know — would the impatient and proudly Randian Travis Kalanick be, in this fictional universe, seduced by Heilein’s Functionalism? I think maybe! Or would he, according to his company’s insistence on strictly monitoring the ratings of its contractors, be more sympathetic to the bureaucrat who concludes, when stability is restored, that “supervision and inspection, check and recheck, was the answer” all along? Or is he just putting off worrying about any of this until drivers are replaced by actual robots.