A Decade Later, Whither the Metrosexual

by Johannah King-Slutzky

When was the last time you considered the metrosexual? If you are a reasonable person — not this guy — it’s been about ten years. Or at least I thought so, until, after a decade of silence, three people mentioned metrosexuals to me in the same week. Perhaps because it’s the twentieth anniversary of its coining and the tenth(ish) anniversary of Queer Eye.

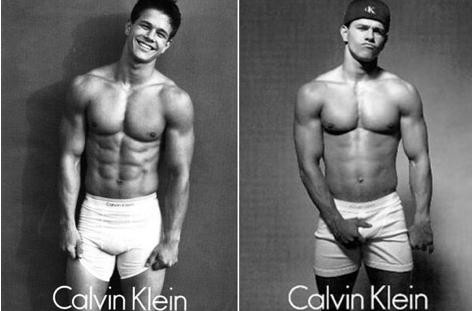

In reconsidering the metrosexual, we must first distinguish between the metrosexual’s imagined and actual properties. Like hipsterism, metrosexuality is an insult more readily slung than substantiated. According to canon, David Beckham is the ur-metro. Although Beckham initially goes unmentioned in the word’s first printing (in 1994), the word’s progenitor, Mark Simpson, introduced American readers to metrosexuality through the British football star in 2002, when he called Beckham a “screaming, shrieking, flaming, freaking metrosexual…famous for wearing sarongs and pink nail polish and panties…and posing naked and oiled up on the cover of Esquire.” Other icons of metrosexuality of the time included Mark Wahlberg and P. Diddy. This was somewhat shocking to me, since I associate metrosexuality with men who resemble heterosexual twinks — your Zac Efrons, your Ryan Seacrests. Hair that swoops, cheeks that apple.

From Mark Simpson’s first article on the metrosexual.

Unlike homosexuality, metrosexuality, one would think, is determined exclusively by artifice. But when I asked friends to delineate that artifice by describing “metrosexual fashion,” there was no consensus (rings? v-neck tees? scarves?). There are also no obvious metrosexual products, and certainly no defining brands — like Sperry Top-Siders are to preppies or Herschel is to hipsters.

From

The Advocate, December 2003. Metrosexuality was omnipresent, but vague.

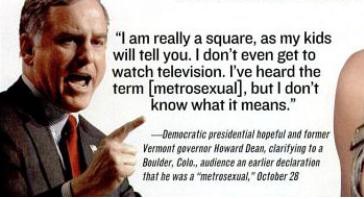

Rather, it seems, metrosexuality is attitudinal and behaviorist: It isn’t about using a certain pair of tweezers, but by using them often. On Urban Dictionary, you just might be metrosexual if “you own 20 pairs of shoes, half a dozen pairs of sunglasses, just as many watches and you carry a man-purse.” Attitudinally, we might ascribe it to what Simpson calls “narcissism” and what I would call, in heavy scare quotes, “indulgence.” This is why it is so outrageously easy to lob metrosexuality at even the muscle-ogre-iest of targets; in 2003, Howard Dean was a metrosexual.

Indulgence is at the crux of metrosexuality’s demise. This is not new. Victorianist scholar James Eli Adams argues that Victorian masculinity was characterized by intense programs of self-discipline, and dandyism is conventionally masculine because its lacquers demand self-discipline to curate and maintain. Dandyism, hipsterism and metrosexuality all toe this line by demanding a disciplined commitmentto narcissism and indulgence. Dandys must starch their linens and tie their cravats; hipsters must update their glasses and curate their records; and metrosexuals like Beckham must sculpt and oil their muscles. The masculine transgression isn’t the behavior, which is not actually strange, but the intent — usually self-love, the desire for desire, or (perhaps this is most shocking of all) self-care camaraderie between men and women. To this end, Mark Simpson repeatedly stresses the soccer player’s body as a kind of misappropriation:

“Becks” is…as famous for posing naked and oiled up on the cover of Esquire, as he is for his impressive ball skills….In the interview with the Brit gay mag Attitude, this married father of two confirmed that he’s straight, but as he admits, he’s quite happy to be a gay icon; he likes to be admired, he says, and doesn’t care whether the admiring is done by women or by men.

Beckham wants to turn his muscles into art objects instead of war (or soccer) machinery. He builds a masculine body but appropriates it cosmetically. He’s happy to be gazed at by men alongside women. And while the gay male gaze is not new, what made Beckham unusual was his mentality — he was happy to use his body “inappropriately.”

Because metrosexuality is defined by the intentional misuse of masculine bodies, metrosexuals simply disappeared once their behavior and attitudes cease to be targeted as indulgent. For metrosexuality to die out, its few concrete practices needed only to become familiar — and since most of metrosexuality’s few material practices were consumerist, they were easily made ordinary. So of course metrosexuality died quickly. It was born with a congenital defect.

One of metrosexuality’s functions was to safely excise gay panic. Metrosexuality, like the bromance (another metrosexuality-killer), is extended clickbait for “no homo.” For example, a discursive analysis of YouTube makeup tutorials by and for men identified permutations of “I’m metro, not gay!” as a common defense in YouTube videos and video comments. Commenters made their heterosexuality explicit (for example, “Hey bro…my girlfriend loves having a guy who can look flawless”) or else insisted on their masculinity, as when one explained that highlighting his cheekbones for contouring gave him “a more masculine look.” Relatedly, men’s YouTube makeup tutorials tend to use technical language like “everyday protection” and “fragrance free” and employ authoritative rhetorical devices like identifying perceived flaws (“acne, scarring, redness”) in sets of three.

Metrosexuality equivocates: conservative epithalamium? Or liberator of men? Episodes of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy played this trope straight (ha) by sometimes cleaning up their charge expressly to ready him for a proposal. In queer theorist Jeremy Kaye’s words:

What is significant about [Queer Eye] is that perpetually ‘‘single’’ gay men are supporting the institution of marriage, an institution which they are legally excluded from participating in. So integral for the straight man’s make over, the Fab 5 are now relegated to the sidelines. They are only able to watch and ridicule as what feminist and queer theorists in academe call the ‘‘heterosexual matrix’’ reasserts its hegemony.

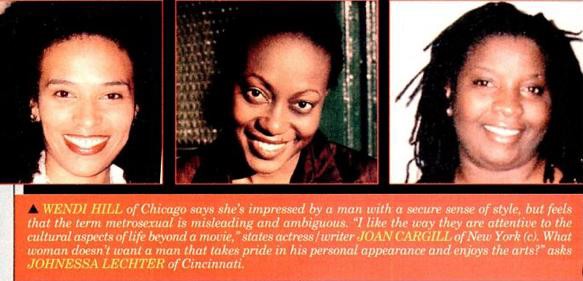

Trend pieces that interviewed women for their views on metrosexuality underscore this problem. Judging by the press, metrosexuality only attracts or repels. Although he is supposedly “killing sexuality,” the metrosexual lubricates conversation about heterosexual attraction. When questioned, women chose between only two responses: yes, I like metrosexuality because I want my man to smell/dress/look good; or no, I hate metrosexuality because I prefer a “manly man.” An astonishing amount of press-coverage asked women to weigh in on this question, provoking diatribes like this:

I certainly can’t speak for all women; but among my group of girlfriends, he’s known as the icky dude who’s in touch with his feminine side. In college, he was the Euro guy. He likes to spend $40-and-up on Kiehl’s facial cream, use my loofah, get a pedicure and make creme brulee. He likes shopping and beauty products, but — get this — he still wants to date me and my friends! That’s it. I’m destined to live a life of loneliness and solitude.

>

Jet, Feb 2004

Ironically, metrosexuality chiefly fascinates women. According to Nielsen figures, fifty-six percent of Queer Eye’s viewers in October 2003 were women eighteen to forty-nine. Perhaps some of them, imagining their own makeovers, identified with the Fab 5’s ward? Or else, quoting again from Kaye, “the true intention behind this makeover is always that the straight guy’s girlfriend or wife will be happier.”

The last ten years have witnessed enormous changes in popular attitudes toward gay men, making that kind of “no homo” containment less urgent. Metrosexuality sounds like homophobia’s vespers. Relatedly, implicitly anti-gay metro trend pieces easily became exercises in gender differentiation. In 2004, “He’s on my turf” was a common female refrain in the metrosexual trend piece. For example:

The metrosexual, no doubt, can rival any woman with his skin and hair obsessions…First though, let us continue with the men: Irritable Men Syndrome (IMS): ‘Anger and irratableness caused by a sudden drop in testosterone levels, particularly when caused by stress.’ Are they kidding? Women have had a stronghold on PMS for centuries. Now we have to share our irrational behavior with men?

Metrosexuality, in other words, also expressed discomfort with changing gender roles. Today, that need is met by handwringing of the “can women have it all?” variety: Famously, the object of “The End of Men” is women, but ten years ago, the same headline might’ve topped a trend piece on men who buy fancy soaps.

What was narcissistic yesterday might be just another selfie today, but there are material links between dandyism, metrosexuality, and the more recently-deceased hipster. A genre known as the “male conduct book,” a nineteenth century how-to guide for insecure young men in search of purpler plumes, both substantiates the metro-hipster link and underscores metrosexuality’s conservativism.

The prototype male conduct book may have been Under Two Flags, a now-forgotten bestseller of the late eighteen sixties, originally written as military periodical. Its protagonist, a soldier named Bertie, was heavily coded as a dandy. He has a “dandy’s lamentations and epicurean diatribes”; his sidekick, Mr. Rake, is a pun on the slang for sodomite, and Bertie’s own nickname is “Beau Lion.” “Beau Lion” is impressive enough to modern ears; what you probably won’t detect is that both “Beau” and “Lion” were popular nineteenth-century names for dandies. Among Bertie’s glamorous possessions you’ll find “Bohemian glass, gold-stoppered bottles, perfumes of Araby, a silver dressing-case, brushes, boot-jacks, boot-trees, whip-stands, tiger-skins, a retriever, a blue greyhound, [and] crossed swords.” And this was a bestseller among male soldiers!

Over a century later, the male conduct book resurfaced to channel masculine angst in the early aughts with titles like The Metrosexual Guide to Style: A Handbook for the Modern Man (2003) and, of course, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy itself, which, if you’re particular about your conduct “book”definitions, also comes in paper form as Queer Eye for the Straight Guy: The Fab 5’s Guide to Looking Better, Cooking Better, Dressing Better, Behaving Better, and Living Better (2004). The hipster equivalents are The Hipster Handbook (2003), Vice’s “Do’s & Don’ts,” and Hipster Runoff. Like Victorianism’s masculine asceticism, The TV Queer Eye highlighted (and ironized) male discipline with a segment called “Boot Camp.”

But metrosexuality, hipsterism and dandyism are fascicles, not transposed equivalents. My answer to “whither the metrosexual” is only partially “the hipster.” Key elements of the metrosexual are missing: for instance, hipsters can be women, which dandies and metrosexuals cannot. Metrosexuality and hipsterism share conspicuous consumption; both have been charged as narcissistic, but their narrative conventions diverge. Metrosexuality’s buzzword status reflects the early aughts’ fomenting of gender anxiety into trend pieces, but hipsterism is probably more anxious about labor and nostalgia. (On labor, nostalgia and hipsterism, c.f. vintage fashion, artisanal shit, the working class.) Hipsterism has no marriage plot, and metros might take their coffee poured-over, but they won’t drink it from a jam jar.

What could be more indulgent than drinking hot chocolate in full fleece and boxy glasses while the nanny state pays your medical bills? For this, pajama boy was called “a metrosexual hipster” — the missing hipster-metrosexual link.

Likewise, the “gentlebro” (a trope-name of my own devising) re-branded many of metrosexuality’s grooming practices with more traditionally masculine images. “Men’s products” such as Dove’s “Men+Care” line of face wash, body bars, and hair shampoos transformed and destroyed metrosexuality by urging men to lather up in a masculine way. The subtext is not very sub. One of Dove’s Men+Care ads depicts Villanova’s square-jawed basketball coach selecting between a blurry Old Spice bottle and Dove shampoo. “How important are decision-making skills in your profession?” asks the interviewer. “As a decision-maker, which [soap] would you choose?”

In a sense, the men’s care industry killed metrosexuality by co-opting metrosexuals’ grooming habits and repackaging them as masculine and paternal. Same goes for the renaissance of old-school men’s shops, where conditioning skin and softening hair is neither “metro” nor “narcissistic,” but “classic,” and “quality.”

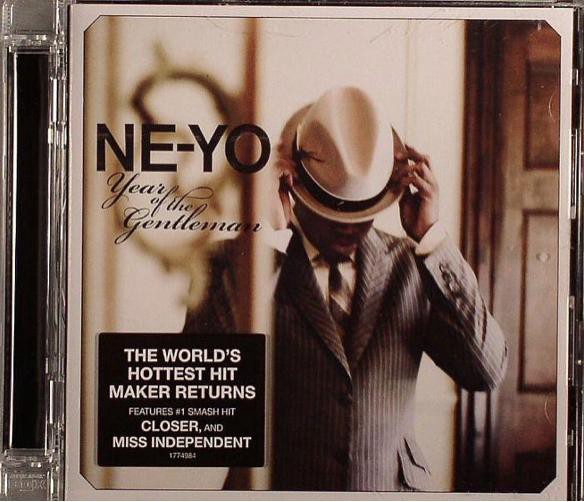

Still going strong, the gentlebro of men’s care developed serious pop culture clout in 2008 with the advent of Don Draper suave and R&B chivalry, which ironically stretch men’s comfort zones by appealing to conservative, Sinatra-era imagery, such as men in fitted pinstripes and felt hats.

2008, Year of the Gentleman

Feminist scholar Heidi Hartmann defines patriarchy as “Relations between men, which have a material base, and which, though hierarchical, establish…solidarity among men that enable them to dominate women.” One would be remiss to go without noting that the world’s biggest cosmetics companies include L’Oreal, Estée Lauder, Proctor & Gamble, and Johnson & Johnson, all of whom have male CEOs. So, while I may be oversimplifying, it seems plausible that the growth of a men’s care industry primarily benefits men. In this light, metrosexuality ticks off most if not all the boxes for patriarchy. It is a way for men to relate to each other; it has a material base; the industries it supports are hierarchical and at the top exclude women; and it generates solidarity between men.

If you denude “metrosexuality” of its label, little has changed for men since 2004; metrosexuality’s constituent parts have simply fractured into other identities and anxiety-loads. The hipster, the bromance, even R&B’s and Mad Men’s resurgent interest in gentlemanly suave are all redoubts against the genderless dys- or u- topia that metrosexual ideologues forewarned. To steal John Herrman’s line, metrosexuality was killed by “whatever combination of factors led to all the bad hats.” The remaining gender anxiety has shifted onto women, who are not ending the metrosexual, but men. And don’t forget the selfie, social media, and the Brooklyn male novelist, which have usurped metrosexuality’s role as patsy in the war against narcissism.

Still, the real fault lies with metrosexuality itself, whose very definition as “men misusing in their bodies” can’t sustain life for more than a couple years before yielding to the sense that so much indulgence is actually just business as usual. Interpret this as good and bad news: there will always be more men.

Johannah King-Slutzky is a blogger and essayist from New York City.

Top photo by François