The Founder's Dilemma

A terrifying new video game is a little too real.

In Alexander Bogdanov’s 1909 novel, Red Star, a Bolshevik labor organizer flies on a spaceship to Mars, where he finds a fully developed communist utopia. The factories are connected to an elaborate control room that monitors all supply shortages in real-time; there’s no want, so demand isn’t monitored. There’s no money; it’s no longer useful. Workers take what they need, in whatever quantities they choose. In Francis Tseng’s dystopian business simulator video game, The Founder, the first-person player visits Mars, but won’t find a demand-free utopia. Earth’s markets are exhausted, and Mars is being used for its resources and freshly created markets, through a form of monopolistic post-human capitalism that’s just as neatly networked as Bogdanov’s perfect communist society.

At the start of the game, it’s 2001, and you’re at the helm of a startup. You’re working out of a small apartment, in the Lower East Side of Manhattan maybe, and, through some combination of elbow grease, corporate domination and American Individualism, you’re going to make something — and, not inconsequentially, you’re going to make a lot of money.

The game ends when, after replacing all of your employees (and consumers) with robots and clones, you’ve built what Tseng, a 28-year-old designer, developer, data scientist and artist, who is currently a researcher in residence at New Inc, calls the “Founder AI,” a program designed to automate the player’s job. The first thing it does as CEO is fire you.

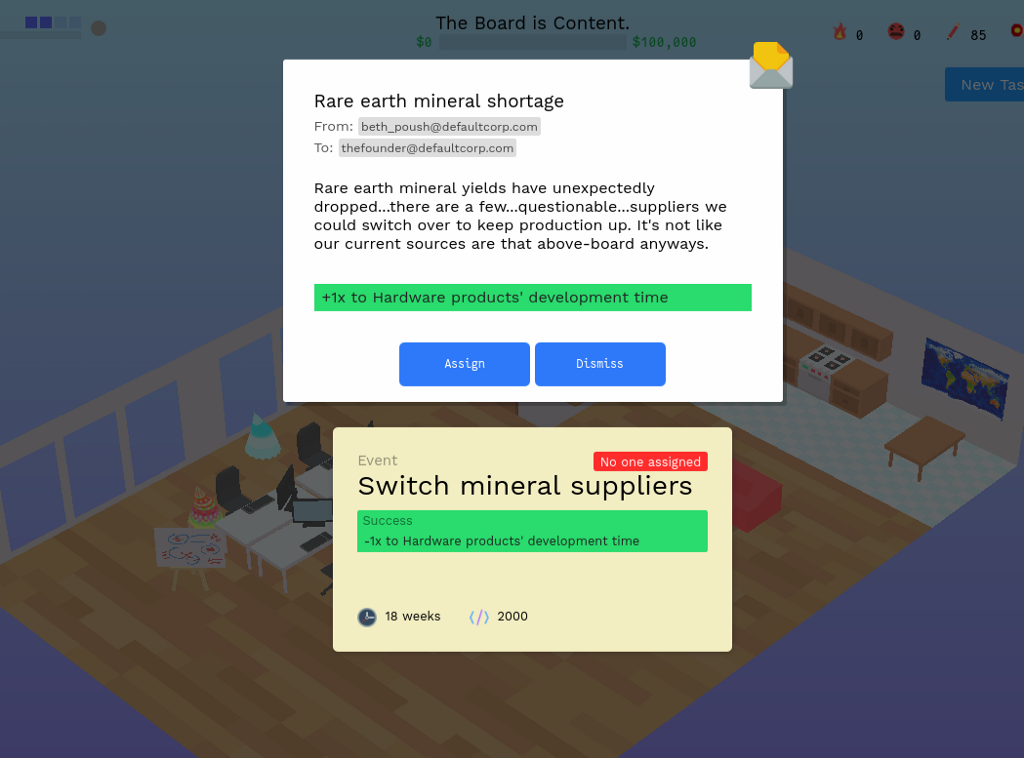

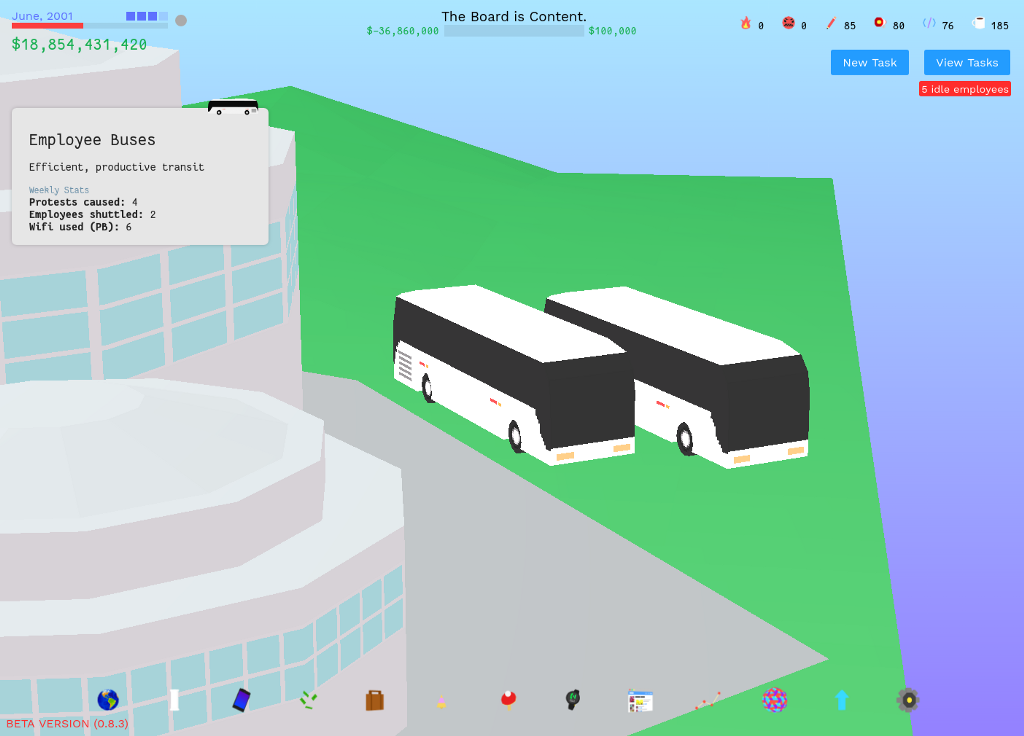

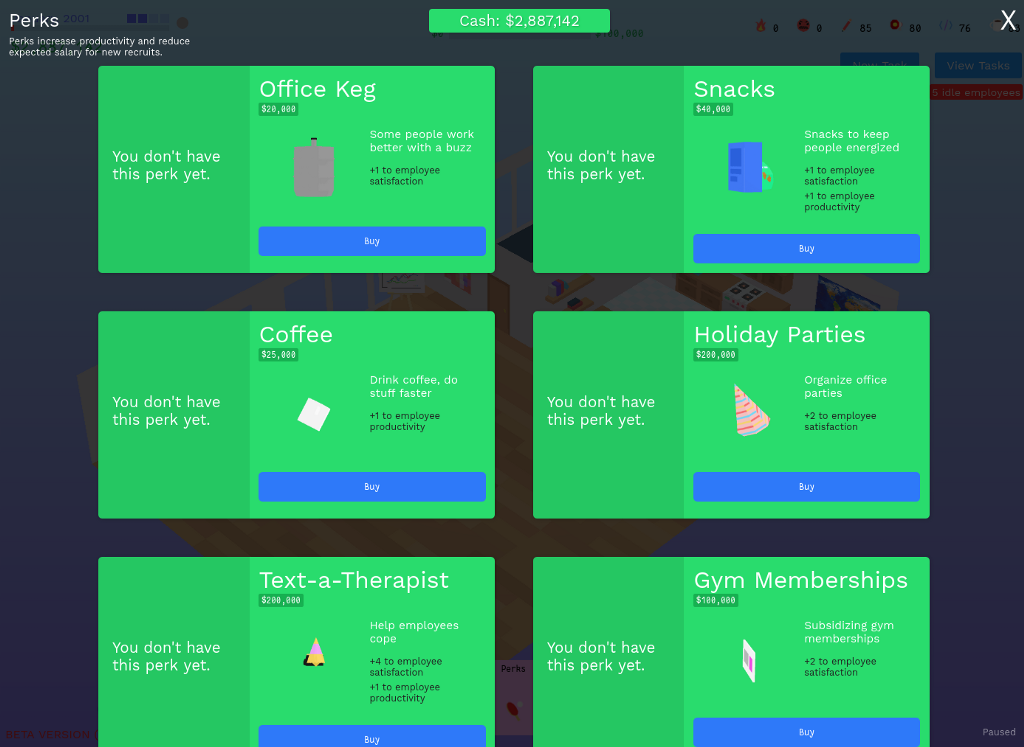

Between the beginning and end of The Founder, you’ll hire new employees in a dialogue-based mini game, where the goal is to say the right things to get your prospective employees to accept the lowest possible salary. Some of the prospects, marked as “privileged,” will gladly accept a lower salary, because they can afford to; others are marked as “cynical” and are harder to please. You can buy increasingly elaborate and absurd perks for your office to attract the hottest talent — start with coffee, then upgrade to butter coffee; an office keg upgrades to microbrewed beers; unlimited vacation to “vacation implants,” which simulate a vacation so your workers never have to leave the office.

The Founder is a management-simulation game in the tradition of SimCity and Civilization; the player acts as God over a population of simulated subjects. These games may be intricate, beautifully designed and enormously popular, but they are also known for exposing the parameters of our civil imagination. In SimCity, as Ava Kofman points out in Jacobin, the player is bound to the strict logic of neoliberal urban planning. Crime’s up? Your only choice is to build police stations. She writes, “Certain questions are raised (How much can I tax wealthy residents without them moving out?) while others (Could I expropriate their wealth entirely?) are left unexamined.” The game’s most recent incarnation, SimCity BuildIt, for iPhone and Android, incorporates what can only be described as a “disaster capitalism” scenario: The player opts to destroy parts of their own city, through a cartoonish evil-scientist character called Dr. Wu, in order to rebuild them for more profit.

Other indie game developers have been at this, too. Subaltern Games, makers of No Pineapple Left Behind — a game, meant to show how tying high-stakes testing to state funding in public schools fails — in which teachers turn their kids into pineapples, which, turns out, are more tractable. Neocolonialism, another of Subaltern’s games, is, in the game’s own words, “about finance bankers attempting to extract as much wealth from the world as possible.”

The Founder and Subaltern’s games turn the Sims logic on its head, or, perhaps, compound it ad absurdum. It places similar, simplified and deliberate constrictions on the player’s actions, confining them to the strict logic of ceaseless corporate expansion in an effort to illuminate its dark path toward human obsolescence. Full automation and the pursuit of endless profits, The Founder suggests, may lead us to an economic system in which human beings have no value to the market, in which the market operates independently of, and without regard for, human life.

“Computers were always part of my life growing up,” Tseng said. He hung around AOL chatrooms, and internet forums, finding community on the web. After college, where he studied cognitive neuroscience (“out of an interest in understanding human decision-making processes and how they apply to design”), then he moved to Beijing. He has family there, but, at the time, had no serious job prospects. “When I graduated, it seemed like the only two paths were more school or going to a lab, or both, and I wasn’t really interested in either.” He managed to land a job at a startup, where he learned web development and design. A year later, he moved back to the States and got a job at IDEO in San Francisco. It was during his time in S.F., he says, that he was exposed to “the heart of the tech world” and came up with the concept for The Founder.

“The juxtaposition of tremendous wealth and a city that is struggling with homelessness and drug abuse, that amidst these companies working on new technologies and ostensibly, in their eyes, pushing the needle on human progress, these basic persistent problems are ignored by them,” he said over email. The hiring mini-game is based on his own experiences interviewing with such companies—he’s seen what kind of people tend to win out in the startup job market. “One of the main things I want to show with the game, the malice of this neglect, and the tunnel vision that accompanies founding a startup. That twisted logic that governs how so much of this country operates is in so many ways cranked up there, deep in the insulated tech world.”

The Founder is in dialogue with a body of post-capitalist literature that’s come out in the last few years, most notably the “accelerationists,” a group of Marxists futurists, comprising primarily the BBC journalist Paul Mason, Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek, the latter two both lecturers at the City University of London, who wrote the accelerationist manifesto, Inventing the Future. The labor movement, in their view, is antiquated and defunct. The twentieth-century left — focused as it was on what the accelerationists call “folk politics,” as well as building worker solidarity — has no solutions for our current moment. Full automation, they argue, will move us closer to an egalitarian utopia. n+1 aptly described their outlook as, “I for one welcome our new robot overlords.” Tseng has read them; he’s described his politics as loosely in line with theirs. But The Founder has an even darker take on automation than the accelerationists. Press for automation, the game may suggest, but take note of who owns the robots.

Peter Frase explores this idea in Four Futures, a book-length thought experiment, the central assumption of which is that we will, sooner or later, live in a post-work society. From there, he develops four scenarios. We could wind up with “full communism,” powered by devices like Star Trek’s replicators — machines that will provide us instantaneously with everything we might need or want. In his second future, “rentism,” capitalists retain control of intellectual property, the blueprints for the items the replicators produce. Under rentism, writes Frase, Captain Jean-Luc Picard, who customarily walks to the replicator and requests, ‘tea, Earl Grey, hot,’ would have to pay the company that has copyrighted the replicator pattern for hot Earl Grey tea.” The third is a version of “eco-socialism,” in which the scarcity of an environmentally depleted world requires a centralized and state-driven effort to mobilize resources and labor. Frase points to Pacific Edge, the third book in Kim Stanley Robinson’s California Trilogy, as a fictive example of his future-socialism. It’s a world where “our multinational capitalism has given way to something more socialist, and ecologically sensitive, but without being a total primitivist rejection of modern technology.”

And last, “exterminism,” the future that most resembles The Founder’s world, in which automation has rendered most people useless to a ruling class. “The great danger posed by the automation of production,” writes Frase, “is that it makes the great mass of people superfluous from the standpoint of the ruling elite.”

But The Founder isn’t exactly exterminism. The player’s end goal isn’t “communism for the few,” but the endless profit for the company you’re running. In theory, you’d need to maintain a consumer base to keep up the profits. But, in Tseng’s dystopia, that’s not necessary: “What I want to also acknowledge,” Tseng told me last year, “is that there’s this tension, if you fire the employees who were the consumers, who’s actually paying for your product anymore? It ultimately becomes totally circular, so that the robots need the product.” You can produce “social goods” in The Founder, like telomere therapy, which would, in theory, keep our DNA from unraveling as we age and allow us to live forever. But the human body, in the end, has no place in this closed system — the monopolistic capitalism of The Founder’s imagining. The only thing that’s immortal in this game is the corporation you’ve built.

“One of the main issues is disproportionate representation in startups, who has power,” Tseng told me. He brought up the “privilege” tag, placed unassumingly on character profiles, “where they get bonuses to everything. … It’s such a powerful bonus that if you’re operating within the mindset of the game, which is that you need to continually profit every year, is that — if you have the option — you’re always gonna go with the people with the better skills cause they make everything easier.”

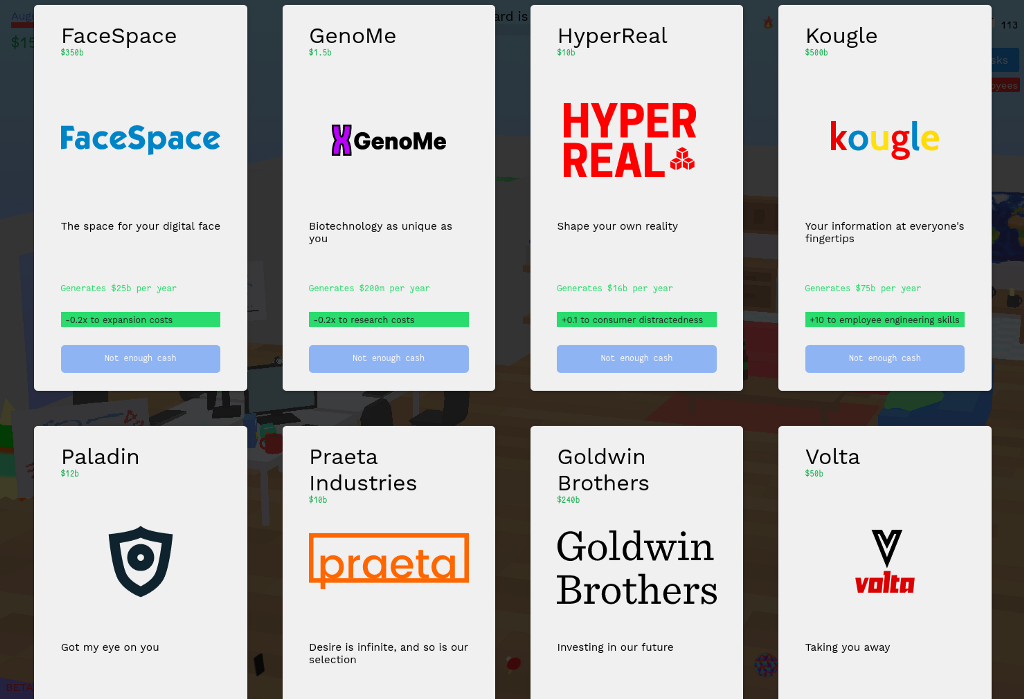

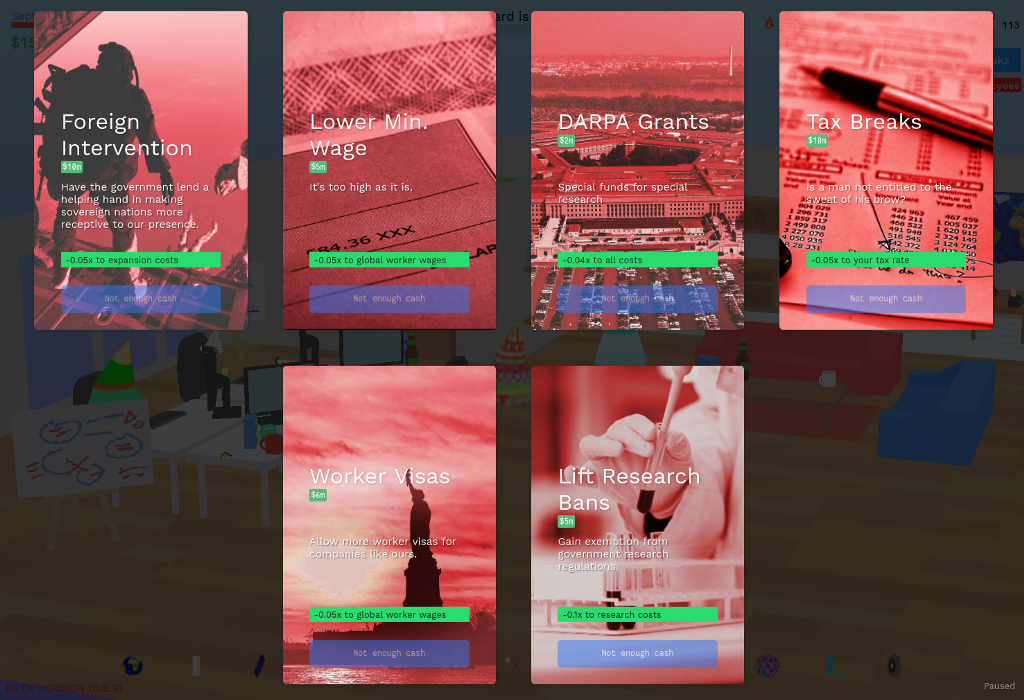

Those skills make it easier to “innovate,” a process which, in The Founder, boils down to simple combining of startup-y product types. For example, pair “social network” and “ad” and you get “FaceSpace,” which, in addition to generating heaps and heaps of money, gives you additional insight into your prospective hires: You can see their social media profiles on a platform you own. Combine “genetics” and “synthetic organism”: you’ve invented “DNAnimals.” “Defense” plus “genetics” equals “GeneKill.”

Once a product is developed, it competes on “The Market,” a mini-game that resembles a board game, in which products vie for market share against competitors. (The market may be the most boring and repetitive part of The Founder, but not long into the game, you can assign an employee to play it for you.) As you expand, you’ll eventually acquire your competitors, who have “Silicon Valley”-esque names like Kougle and GenoMe.

The only insight you get into the outside world is through “the news,” a goofy, algorithm-generated web page, featuring headlines like “At Lehman, a Facebook is Muted.” You have access to the site but are entirely welcome to ignore it. And though some decisions you make, like lobbying to lower the global minimum wage, will provoke a response in the newspaper, the press response has essentially no influence on the success or failure of your company.

“There’s still this trope of dystopian futures being presented in a particular way,” Tseng said. “Like Children of Men, very gritty, that kind of thing. But you don’t really see that whole Brave New World kind of dystopia developed that much anymore, where you can only see what’s in your office. In The Founder, you can see these abstract markets and stuff, and the only glimpse you have into the world beyond that is through this news site, which you can choose to ignore.” And you can’t really lose. If the board of your company fires you, you can start over with whatever cash you had left over from your failed enterprise.

The game sucks you into its logic quickly. When I first started, I felt some sense of responsibility to my employees and the people who were to make use of the products I was churning out. Low-income market shares, in the market mini game, seemed to have value for moral reasons, even if they were less valuable in context of game itself. That dissipated quickly. Those low-income shares, represented by a tile with a single dollar sign on them rather than the two-, three- or four-dollar sign tiles that represent the higher-income market shares, have only financial value to the player. Poor people, in The Founder, are basically worthless. Only high-income and luxury market shares are really worth your time.

At the outset, you may feel that you should care for your employees. Clicking on the little cones that represent them lets you see their most recent tweets to get a sense for whether they’re happy or not. You might buy them additional perks — say, some snacks — to try to please them, or run a promo campaign to build some hype around your company (which has the benefit of boosting both profits and employee morale). Soon, though, you’ve replaced everyone with clones and robots, and you don’t care about keeping your robots happy.

Tseng hopes that players will develop this kind of callousness toward their workers, and he wants people who work in tech to play the game. “I was living in San Francisco at the time, 2012 maybe, when I came up with the idea,” he said. “I was really immersed in the startup world, and it was really bizarre — it felt very disconnected from the world but also has a disproportionate influence on the world.” A few years later, he funded The Founder on Kickstarter. It was featured as a “Project We Love” on Kickstarter, a fundraising site for startups.

I’m certainly not the intended audience for the game (I’ve never worked in tech). But the flatness of The Founder’s caricature might preclude it from convincing anyone in tech who doesn’t already see things from Tseng’s perspective. The game’s glib cynicism, the fact that Kickstarter “loved” it, the forthrightness with which it marches toward the points it’s very clearly making might all be indications that any disaffected employee at Google who comes across The Founder might just shrug and think, “Yeah, I know.”

But glossing over the game as a tongue-in-cheek, easy jab at tech doesn’t mitigate that what’s perhaps most terrifying about The Founder: many of the technologies it describes are either real or imminent. A Japanese company voted an algorithm onto its board in 2014. Bigelow Aerospace, a space technology company, filed a request with the Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation asking for a “zone of non-interference” around their future operations on the moon. Amazon forecast for its fourth-quarter operating income between zero to $1.25 billion. The ultra-rich are building bunkers, complete with hot tubs and bowling alleys, preparing to isolate themselves in the event of environmental catastrophe or revolution.

Tseng isn’t so much a game designer as a simulator. His other work is inspired more by the type of technology found in Red Star, the cybernetic planning systems that sit at the center of futuristic national economic planning projects. In 1971, Chile built a real-life version of it, Project Cybersyn, which came fully-loaded with a futuristic, Starship Enterprise-like control room, which was called “the operations room.” (This room was designed to, in theory, plan a national economy, and to do so quite comfortably: each of the seven chairs in the operations room was equipped with an ashtray and spot for your whiskey glass.) It was the most fully developed attempt at exactly the kind of economic planning that Bogdanov describes in Red Star.

The creators of Cybersyn hoped that both workers and administrators would sit in the operations room, that the system would take input from workers on the shop floor, giving workers a voice in management. In short, the idea was to see all the data, identify shortages, and be able to correct for them all from a single computer system. (If a cybernetic system were to be developed and implemented within a neoliberal market system and not in Chile’s socialist system, would it divest people not just of their labor but also their value as citizen-consumers? That’s what happens in The Founder.) The project never got off the ground. Pinochet, with the US’s help, overthrew the Allende regime before Cybersyn could be implemented and tested. Given that computers were in short supply in Chile, it likely wouldn’t have worked.

Tseng’s current project, with New Inc, an incubator run by the New Museum in New York City, is to explore the uses of simulations and modeling, It’s wonky work: these simulations exist already in academia and industry, but Liu and Tseng see an untapped resource in the uses of simulation as a pedagogical tool for broader audiences. The main focus, Tseng says, is using simulation as a methodology for understanding, designing, and experimenting with systems, particularly through “agent-based modeling,” a type of simulation where the behavior of individuals is modeled to see what phenomena emerge when they interact. Their models may create narratives, satirical art, or the inputs that drive an operations room in Cybersyn-run economy. Their work could, in short, turn New York into a real-life SimCity.

The Founder, like SimCity, is built on this type of systems thinking. Financial products like credit induce consumer debt, defense products increase the death toll, and biotech products like genetics-based social network increase what Tseng calls “moral panic.” All of these lead to increased outrage, which the player must negotiate (primarily by making entertainment products and sponsoring music festivals). Where The Founder obfuscates, Tseng’s work with New Inc seeks to illuminate — to show those variables that we don’t readily see, in the real world, that drive our cities and our relationships.

Where, then, are the humans at the end of The Founder? Are they dead? All we know is that the corporation serves them no longer, that they’ve been cut out of that loop entirely, rendered useless to its cycles of production, that capitalism doesn’t need them. For all we know, they’ve fled, and are living happily outside of capitalism, in a solar system next door, perhaps. They may be reaping the benefits of automation in a communist utopia having left capitalism running on its own self-sustaining, all-consuming, fiscal-year-length loop.