The Ebola Franchise

An Ebola outbreak in West Africa has killed over 650 people, making it easily the deadliest in the disease’s relatively short history. It has also brought us one of the weirdest Times op-eds you’ll ever read. It scans almost like an example or a template: Just replace “Ebola” with any other bad thing, adjust proper nouns in the “do better” sections, and SEND IT TO THE PRESSES. Some of its recommendations:

-Infected individuals must be isolated in health centers to prevent the virus from spreading to others and to give them the care they need.

-Bodies of victims must also be disposed of with care: The virus, present in bodily fluids, including sweat, is most infectious at the end-stage.

-Then there is widespread ignorance among the most vulnerable populations about what needs to be done. The result is that many people are hiding sick loved ones at home and transporting bodies for burial with no understanding of the precautions they must take.

“Then there is,” yes. Then there is that. Then there is this, too:

-The governments of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Nigeria must also act with equal urgency to raise public awareness, put additional trained medical personnel on the ground and trace patients’ contacts with others.

-[T]he whole of West Africa must act to contain it.

Yes. Strongly agreed: This disease is bad, and people affected by it should really try to stop it.

Maybe it’s difficult to talk about Ebola when it’s actually killing people, lots of people, because the rest of the time it’s treated like a trope.

I’m certainly guilty of this; I’ll read almost anything about infectious diseases, and in retrospect, most of this reading was cold and sociopathic. Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone was an escapist thriller; The Great Influenza was an apocalyptic period piece; The Coming Plague was an engrossing feat of science fiction world-building, about a planet that contrives, almost at random, new and hideous microscopic monsters to destroy sophisticated life, and that will not give up until it has succeeded. Nature finds a way, a narrator intones, except that this narrator is a doctor who has spent her whole life watching people die in pain and confusion, and I’m just sort of dozing off, because I’ve been reading too long and it’s time for bed.

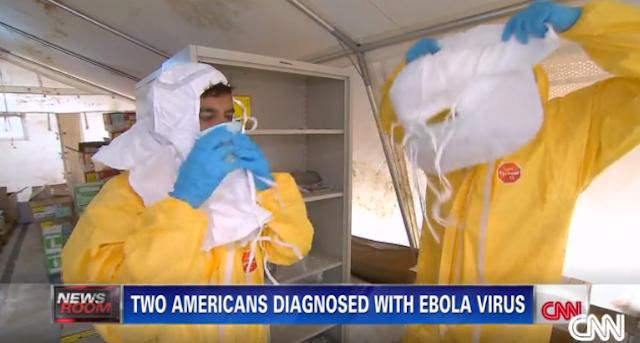

This is of course an insane way to read about deadly diseases. It is also standard in areas of the world where these rare viruses feel utterly remote. It provides comfort that your incidental version of civilization at least shields you from the most vividly horrific diseases. Cancer, which kills millions effectively at random, is banal and civilized in comparison, carrying out its gruesome task under fluorescent lights, amidst highly paid professionals and machines and stacks of forms, without splatter and gore. Distant horror stories allow readers to engage with the idea of the apocalypse, of total human destruction, of random death in a different medium than usual. You could sit down and suspend your disbelief for the length of a Romero movie, or you could just flip on CNN and watch the chyron writers do their best “TV in the background during a disaster movie” impressions while anchors listen, visibly concerned, to expert guests reciting containment advice to an audience that is sitting on the couch.

Leigh Cowart, earlier this month, tried to fix the frame:

Monsters that live in the dark are often far more terrifying than those subjected to the bright lights of inquiry and context. Reducing them to something we can catalogue turns their unimaginable horror into something more familiar. There’s a reason H.P. Lovecraft left his horrors undefined: your brain, left to its own devices, can and will conjure fear on a grand scale. And so it is with Ebola: we know the horrors of “average” deaths. There’s at least a general idea of how cancers kill, or heart attacks, or strokes. But Ebola, far away and ripe for the imagination, has grown legendary — and, like most legends, the truth is not quite as awesome as the tale.

You can read the vague, directionless advice-giving, which American interviewers extract from virtually every interviewee — we must educate the people that you do not know, we must contain their virus — as consistent: If Ebola-as-entertainment makes suffering soft and theoretical, then its solutions should be the same.