Selfies from the 9/11 Memorial

by Leah Finnegan

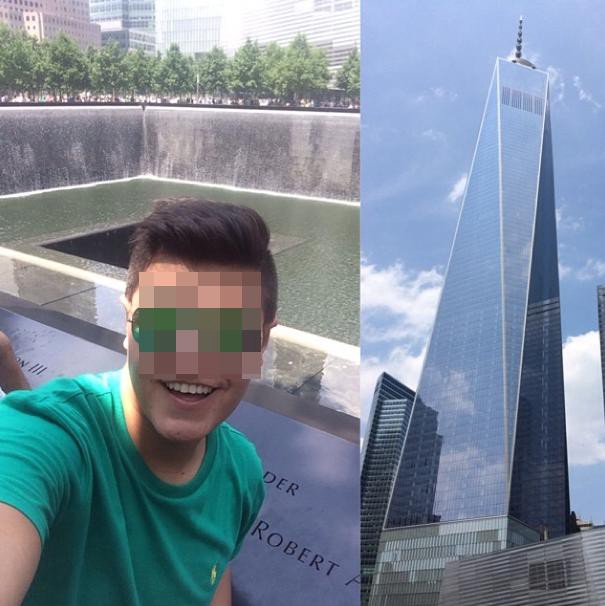

On a recent afternoon, an older man and woman self-consciously configured themselves in front of the south reflecting pool at the 9/11 Memorial. The man placed his hand on the woman’s hip in an awkward clasp and grinned broadly as another person took their picture with a digital camera. A girl in a Yankees cap took a selfie with her camera phone, the Freedom Tower soaring into the sky behind her, the reflecting pool draining into nothingness. She was smiling. An Ethiopian man asked me to take a photo of him and his family. They wore blank expressions, though the youngest girl with them hammed for the camera with her scooter.

The 9/11 Memorial, officially titled “Reflecting Absence,” is a superlative site. It is the most expensive memorial in America, at a cost of five hundred million dollars (up from a preliminary estimate of a hundred and seventy-five million dollars). The two reflective pools are built in the footprints of the twin towers, and contain the largest man-made waterfalls in the country. The contest for the memorial design yielded more than fifty-two hundred entries from sixty-three countries. Other ideas included towers built from Lego blocks and clocks stopped at 9:11. Michael Arad, an architect from New York, won the project, along with Peter Walter, a landscape architect.

The south reflecting pool of the memorial gets considerably more traffic than the north pool. Panel S-38, at the southeasternmost corner of the south pool, near the memorial’s entrance at Liberty and Greenwich streets, sees a bounty of visitors, probably because it’s closest to the entrance. Children climb on it. Families pose for photos. Tired tourists hang their bodies on the marble slab, obscuring the panel’s names — Sebastian Gorki. Hernando R. Salas. Joni Cesta. The memorial, as it stands, often functions more like a tourist rest stop than a place of somber reflection. When I visited on an oppressively hot early July day, visitors dipped their hands into the reflecting pools and poured the water onto their heads and legs to cool off. They leaned on the marble panels with the names of the dead to eat snacks, even though there are no food vendors or trash cans allowed on site.

Whatever tourists’ regard for the sanctity of the space, photographic devices occupy the hands of the young and old visitors alike. Taking a photo at the memorial might as well be one of the memorial’s numerous rules, right next to the one prohibiting soap (no bubble baths in the fountain). Visitors from all over the world readily post photos of the memorial to social media. One photo on Instagram features a smiling couple in sunglasses in front of one pool. You can see the name “James,” and part of what appears to be “Christopher,” on the panel behind them. The caption reads, “Enjoying New York before the missionaries arrive tomorrow!” Another user appears to be on a date: A picture of her and a man in front of one of the pools is captioned with “City date with this kid [heart emoji].” One person left a comment on the photo: “ADORBS.”

A popular hashtag on 9/11 memorial photos is “#speechless.” The caption for one photo reads, “Such a touching place,” followed by a crying emoji. Visitors often wedge white roses into the names that are etched into the marble panels; these are popular for subjects for photography. “Rest in peace [flower emoji],” one user wrote. On another rose photo, someone commented: “Why’d you put a piece of popcorn on the names of people that died? Is that symbolic of something?” The photographer replied: “it’s a rose dude…”

Discussing my visit to the memorial with a friend, he asked, “Why does the 9/11 memorial allow people to treat it so casually?” This question has stuck with me, especially as I consider the memorial in light of my recent visit to the Auschwitz Memorial and Museum in Poland. Of course, in one sense, the two sites could not be more different: Auschwitz is a fairly depoliticized memorial of evil, a place where millions of people were systematically tortured and murdered over the span of years; the 9/11 Memorial is a highly politicized ground where thousands were killed in a few unforgettable hours. At Auschwitz, the remains of horror confront the visitor. At the 9/11 memorial, what little is left as evidence of that day is contained in a museum that is buried seventy feet beneath throngs of tourists.

After visiting Auschwitz in June, I argued that photographing and sharing pictures of places where atrocity has happened — specifically, Auschwitz and Birkenau — was essential for recognizing and acknowledging that history.

We should keep posting — and sharing — photographs of places where horror has happened until these places inevitably disintegrate, even if the photo of such a place does not fit so neatly into a social network, where the crass language of the sharing community — “likes,” “hearts,” “selfie,” “re-gram” etc., etc., can denigrate the austerity of an image. If we use social media for only the happy or banal events in life — weddings, brunches, signs with terrible grammar — well, why bother?

The 9/11 memorial makes me reconsider that thesis, if only because it feels built to be photographed. It’s glitzy, tactile, antiseptic and commercial all at once.

Photographs in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, unlike those of the Holocaust or other atrocities, often did not explicitly show the dead; the event itself utterly annihilated most traces of human existence. (Also, the event itself was photographed, videoed, broadcast and rebroadcast; the plane going into the second tower is like a .gif branded into our collective conscience.) As Susie Linfield, a photography critic and New York University professor, noted in Guernica, a photo of a “severed, bloody, shredded leg and foot lying on the pavement” at a 9/11 photography exhibition was “shocking because it is so grisly, but also because it is so rare.”

Instead, as Linfield has said, photos of 9/11 mostly show New Yorkers coming together. “What 9/11 did produce was a lot of citizen documentation in the days following the attacks,” she told the History News Network. “These were not photographs of the attacks themselves, but depictions of how we as New Yorkers tried not only to survive, but also to help each other and to come together to understand what was happening.”

Building a memorial is not a panacea to processing the ills of history; only time can accomplish that. Major controversies in regards to the memorial at Auschwitz persisted well into the nineties; now that there are so few Holocaust survivors left, the museum is grappling with how it will carry into the future without them. But it’s interesting, and necessary, to consider how the 9/11 Memorial’s infancy sets it up for later life.

Across social media, photos and tributes to 9/11 are pervasive, especially as the anniversary of the attacks dawns each year. Last year, on the twelfth anniversary of 9/11, Instagram’s official blog alerted users to the hashtag #tributeinlight to find pictures of the massive beams of light projected in place of the towers. Mashable, the technology blog, encouraged Instagram users to follow the hashtags “#neverforget, #Remember911, #FreedomTower, #911memorial and #AlwaysRemember” for “more powerful images” (what those are, exactly, who can know?).

There’s something uncomfortable and perhaps uncouth in these recommendations, inasmuch as they don’t motivate users to process the events on their own terms, while the directive is doubly disagreeable because it comes from the corporate entity itself. Would Instagram sponsor a hashtag to mark the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz? (Maybe?) How is it decided where the line is drawn?

The memorial’s Twitter stream, which has 43,400 followers, stays relentlessly on message: Somber positivity. No politics. America. Most every tweet is some form of the same: Retweets of visitors who call the memorial “beautiful,” “gorgeous,” and “so moving!” One retweeted comment reads, “Visited WTC site today and @Sept11Memorial. Very moving and a big crowd paying respect. We’ll certainly #neverforget!” Recently, the feed touted the 9/11 Museum’s display of the bullhorn George W. Bush used to talk to first responders at the site (on loan from the George W. Bush Presidential Library in Dallas). Once, it retweeted former mayor Michael Bloomberg cheering for the U.S. soccer team.

There are not many choices at the 9/11 Memorial, engendering the feeling that there are not many choices in how one can respond to 9/11. Must you be #speechless? Must you gaze in awe at the towering column of the #FreedomTower? “Expressive activity that has the effect, intent or propensity to draw a crowd” is forbidden (except by permission). The entire area, with its looming police presence and forebearing architecture, is oppressive. It’s almost as if the site induces you, with its stringent rules and inhospitable nature, to give up on thinking about it and just lazily photograph it.

According to Linfield, photography can be a defense mechanism when people visit monuments to atrocity. “Perhaps people are shielding themselves from contemplating the horror of the event by photographing it — and photographing themselves at it,” she wrote to me. “This seems like a way to diminish experience, to diminish history, to diminish doubt and uncertainty and contradiction and thought — and hide behind the camera instead.’”

For many people, that may be true. Certainly, at Auschwitz, I felt the need to hide behind my camera at some moments. But at the 9/11 Memorial, I mostly felt uncomfortable. I wondered if you could be suitably and privately horrified by 9/11, but also use the memorial as a grounding for your own politics or feeling about America and terrorism and the people that died. The answer seems to be no. The only acceptable politics is the one dictated by the memorial. The cost of this rigidity is the ultimate vapidity of the site: the ice-cream eating tourists using it to bathe.

As Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times architecture critic, recently noted, the memorial is somewhat awkward. It’s not representative of New York. “The place doesn’t do much to celebrate the city’s values of energy, diversity, tolerance openness and debate,” he wrote. It will take time, perhaps, for this to happen. Maybe it’s a good sign that people are going on dates at the memorial. Maybe that’s a sign of normalcy. It’s definitely a sign of life.

But what does it say about the framework in which we consider 9/11? It’s carefully considered and didactically controlled. As with a photo on Instagram, you have two options when it comes to the memorial: Like it, or say nothing.

Previously: Instagrams from Auschwitz

Leah Finnegan is a journalist and the editor-in-chief of leahfinnegan.com.