A Study in Contrasts

As hundreds line up for Michael Brown’s funeral, the New York Times is running twinned profiles of twenty-eight-year-old Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson and the unarmed eighteen-year-old he shot to death. This is how Wilson’s begins:

On the early afternoon of Feb. 28, 2013, Officer Darren Wilson answered a police call of a suspicious vehicle where, the police said, the occupants might have been making a drug transaction. After a struggle, Officer Wilson subdued the suspect and grabbed his car keys before help arrived, the police said.

A large amount of marijuana was found in the car, the police said, and the 28-year-old suspect now faces seven charges, including possession of marijuana with the intent to distribute and resisting arrest. The incident won Officer Wilson a commendation, presented by the police chief this year as Officer Wilson stood, hands clasped before him, and city officials looked on.

And Brown’s:

It was 1 a.m. and Michael Brown Jr. called his father, his voice trembling. He had seen something overpowering. In the thick gray clouds that lingered from a passing storm this past June, he made out an angel. And he saw Satan chasing the angel and the angel running into the face of God. Mr. Brown was a prankster, so his father and stepmother chuckled at first.

This is how Wilson’s youth is described:

Officer Wilson, who is divorced, was born in Texas but has spent most of his years in these suburbs that surround St. Louis, records show. Family members, friends, colleagues and a lawyer have mostly refused to speak publicly about him, yet those who do paint a portrait of a well-mannered, relatively soft-spoken, even bland person who seemed, if anything, to seek out a low profile — perhaps, some suggested, a reaction to a turbulent youth in which his mother was repeatedly divorced, convicted of financial crimes and died of natural causes before he finished high school in 2004.

“He was a good kid but also a nondescript kid,” said Barney Brinkmann, who coached ice hockey at St. Charles West High School, where some who knew Officer Wilson say he narrowly got enough ice time his senior year to earn a varsity letter.

And Brown’s:

Michael Brown, 18, due to be buried on Monday, was no angel, with public records and interviews with friends and family revealing both problems and promise in his young life. Shortly before his encounter with Officer Wilson, the police say he was caught on a security camera stealing a box of cigars, pushing the clerk of a convenience store into a display case. He lived in a community that had rough patches, and he dabbled in drugs and alcohol. He had taken to rapping in recent months, producing lyrics that were by turns contemplative and vulgar. He got into at least one scuffle with a neighbor.

This is how the personal profile of Wilson comes to a close:

After attending the police academy, Officer Wilson began work in Jennings, another suburb, in June 2009. Robert Orr, the former chief of the Jennings Police Department, said he had no recollection of Officer Wilson and had to call the mayor last week to jog his memory. “Sure enough, the mayor said he was one of ours,” Mr. Orr said. “That must mean he never got in any trouble, because that’s when they usually came to me.”

Yet Officer Wilson’s formative experiences in policing came in a department that wrestled historically with issues of racial tension, mismanagement and turmoil. During Officer Wilson’s brief tenure, another officer was fired for a wrongful shooting, and a lieutenant was accused of stealing federal funds. In 2011, in the wake of federal and state investigations into the misuse of grant money, the department closed, and the city entered into a contract to be policed by the county. The department was found to have used grant money to pay overtime for D.W.I. checkpoints that never took place.

And this is how Brown’s ends:

He was an avid video game player. His favorite games were Call of Duty Zombies and PlayStation Home, a simulation game in which he created an avatar and a city. He was deft with technology and his hands. Once, when his cousin’s PlayStation broke because a disc was stuck in it, Mr. Brown took it apart, fixed it and reassembled it.

Mr. Brown, who constantly wore his Beats by Dre headphones, also was a big fan of rap music. He knew of Kendrick Lamar before he became famous. His favorite group was Migos. And within the past year, he began producing rap songs with friends.

The content varied. He collaborated on songs that included lyrics such as “My favorite part is when the bodies hit the ground.” But he also derided fathers who “don’t pay child support” and rapped glowingly about his stepmother.

He occasionally smoked marijuana and drank alcohol, according to friends. But for his music he adopted a persona to appeal to hip-hop fans, said his cousin, Bryan Douglas, a music producer who was going to help Mr. Brown pursue his music career.

A quiet, undistinguished man who persevered after a troubled upbringing and was perhaps caught up in the wrong department — a victim of the system. A rebellious youth who grew up in a rough neighborhood but had some potential thanks to his family, even though he really just wanted to play video games and rap and smoke pot.

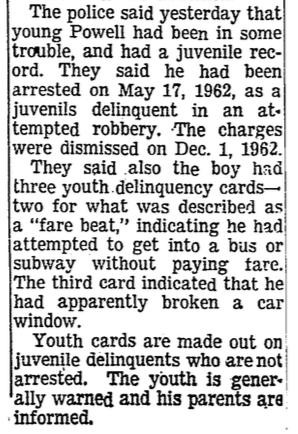

Fifty years ago, a teenager named James Powell was shot and killed by an officer who claimed, contrary to witness accounts, that the boy was charging with a knife. Here is how he was introduced at the time, in the very same paper’s pages:

Powell, five decades ago, was at least granted the benefit of “the police said.”