The German Obsession With Spelling

Deutschland über us.

Of the myriad existential quandaries facing contemporary humanity, here’s one I didn’t expect: Do firefighters have to know how to spell? Just kidding, that’s a German question that Germans asked, so it could not be more expected, because the people who invented a language where you can legit create your own 80-letter compound noun to describe the bureaucracy specifically designed for governing the captains of steamships on the Danube shall not be trifled with. Hence, this thousand-word think piece in the Süddeutsche Zeitung fretting over the fact that some 60 percent of recent applicants to the fire brigade in the northern Spain town of Burgos flunked the entrance exam because they couldn’t spell anything.

But it’s not just about the damn Spanish, insists the Süddeutsche. In fact, “there’s a great lamentation here in Germany about the writerly deficits of our younger generation.” Woe, laments the great lament: at present the Bundeskriminalamt (BUND-us-krimm-ee-NALL-ahmt) — the Federal Criminal Police Office, essentially the German FBI — currently has 820 vacancies. The reason for this? Not enough applicants can pass the spelling test, which may or may not contain the word Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften (WRECKT-shoots-fur-ZIK-ur-ungs-guh-ZELL-shoft-un), a stultifying word for insurance companies that provide legal protection (and, admittedly, a thing that German FBI agents should probably know about, I guess).

The word that starts that monster compound, Recht, is itself deceptively complex given its single syllable. (In fact, I’ve even exegesis-ized about it before. That’s right, I can make up sick compound words, too. Suck it, Heidegger!) Anyway, Recht, capitalized as a noun, means, among other things, law, justice, right and privilege. As a small-letter adjective, it can mean both right and quite (a.k.a. “right” with an English accent).

One of my favorite lines from the magnificent novel Jakob von Gunten by the Swiss author Robert Walser is about a recht vernichtender Schlag (WRECKT fur-NIKT-und-ur SHLOGG), which technically means a “quite nullifying blow” that the title character — whose only goal in life is to become an “adorable round zero” — longs for. But that phrase also carries in it the connotation Recht vernichtender Schlag, a “law-annihilating blow,” something that doesn’t just nullify a person, but also obliterates his right to exist, by obliterating the social order that makes that right possible.

Anyway, Jakob von Gunten, which happens to be my favorite book that was not written by Franz Kafka (and was, coincidentally, a favorite book of Franz Kafka’s) is a magnificent little novel about a school for butlers where no teachers ever materialize, and no lessons are ever taught. So, presumably, the students never learn spelling, the word for which, of course, is Rechtschreibung, which is the entire point of this excellent trip down the desultory memory lane of graduate school (which, coincidentally, sometimes felt like a school for butlers at which no teachers ever materialized and no lessons were taught).

Rechtschreibung. (WRECKT-shribe-ung.) Literally, right-writing. Connotatively: writing justly; lawfully correct writing. So, no wonder the Teutonic get so cranky when you wrong-schreiben. When you misspell to a German, you don’t just overlook the language: you libel it; you defile it; you annihilate it—with, so to speak, a Rechtschreibung vernichtendem Schlag.

Or, at any rate, I do, indiscriminately and constantly.

I shouldn’t be a such terrible speller, in German or any other language, and yet I am. I’m 40 human Earth years old, and that means I grew up doing homework longhand and typed up my German papers in college without the aid of a multilingual spellcheck. Unlike 60 percent of the applicants to the Burgos firefighters’ brigade and (presumably) 100 percent of the applicants to the German Bundeskriminalamt, I somehow managed to pass all my tests and amass a high school diploma, so ostensibly I once knew how to spell in at least one language. But now, as a grown-up, I’m fluent in two languages, somewhat conversant in three more, and proficient at spelling in exactly none/keine/ninguno/nikdo/никто.

Combine that with my standard typing speed of 90 streams-of-consciousness per minute, and the uncanny habit of my Nietzschean abyss of a toddler to require my attention at exactly the moment I’ve got a deadline — and combine that with the German duty to properly castigate the debasers of the Muttersprache (MOO-tur-SPROK-uh) — and you get amazing exchanges like the texts between me and one of my German friends upon the august publication of last week’s groundbreaking investigation of the Society for the Promotion of the Reputation of Blood and Liver Sausages.

In fact, I think there are still typos in that piece, thanks to what my friend helpfully terms my Verschlimmbessern (fur-SHLIMM-BESS-urn), yet another untranslatable compound that more or less means “to make things worse by trying to make them better,” but with a super-mean and dismissive look through teeny-tiny spectacles somehow implied in the word itself.

Anyway, that many typos is ignominious, even for me, and so I did what all people who nominally know German do, and I blamed the Fehlerteufel (FAY-lur-TOY-ful), literally “Devil of Mistakes,” who is, I shit you not, a special mythical demon Germans invented who climbs into your computer and inserts typos for fun and sport, and possibly profit. (A lot gets lost in translation, so I’m not sure about his motivation.)

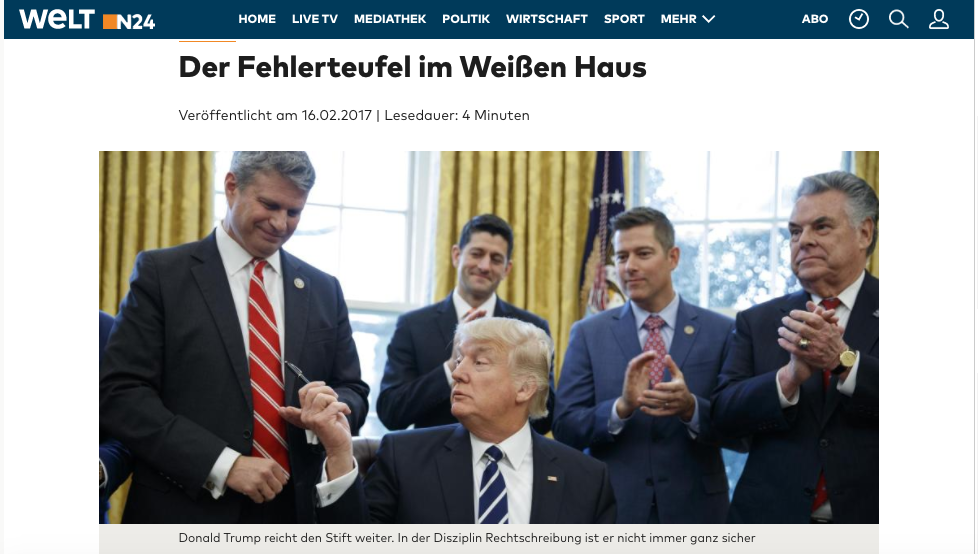

I’m also not sure any Germans buy my excuse, however, because as far as they can see, that particular devil is perpetually busy living inside the Twitter of the Commander-in-Chief. For example, take this recent article in Die Welt (The World, an uptight conservative publication), which someone has cleverly headlined “The Fehlerteufel in the White House.”

This headline ostensibly refers to the imp who (obviously) lives inside Trump’s Android device, but it’s also not-subtly calling Trump himself a Mistake Devil — an epithet that conjures up the not-unjustified tableau of the tufty orange chief executive clambering into the mechanism of democracy in the wee hours of the morning when Jared and Ivanka are asleep, shrieking with giggles as he razes it to the ground with a recht (and Recht) vernichtender Schlag.

Yes, clearly, German Chancellor (and, I can only assume, excellent starer-into-souls) Angela Merkel is going to have a lot to talk about (and possibly spell out, carefully) with President Trump on her alleged visit to the White House less than a week from today. Given the constant onslaught of news from that particular edifice that defies belief, however it manages to be spelled, I cannot even allow myself to imagine the potential ways in which either Trump or Merkel will leave that meeting grievously insulted — and thus, the ways in which that meeting might imperil the precarious order of whatever today passes for Recht.

But whatever happens, Merkel’s visit will give me a lot to think about when I mock how seriously the Germans take their damn spelling. I like to lump their obsession with Rechtschreibung in with their other silly obsessions with doing things “right,” because, like any good American, I like to situate my moral philosophy in a way that excuses my own weaknesses. Still, even five months ago, I would have looked at the latest set of revisions to the Duden (the massive multi-volume dictionary that dictates how to punctuate and spell in German) with my usual knowing snort. But maybe the Germans have always been onto something. Maybe, when the Mistake Devil disrespects the Rechtschreibung, he’s not just defiling the concept of “writing right.” Maybe, just maybe, he’s annihilating the concept of right altogether.