28 Years with Weird Al

by Bex Schwartz

My Bubby and Zaydee came to visit from Florida and I couldn’t wait to share my all-time favorite musician with them: Weird Al. I sang every single song from his first two albums. I showed them the video for “Eat It,” which we had taped off of MTV. “Why do his eyes turn yellow at the end of the video?” I asked, having never seen the Michael Jackson video for “Beat It.” They were slightly confused. “Because sometimes people eat bad food and then their livers don’t work and so their eyes turn yellow,” Bubby said. “Don’t you love it?” I asked. I decided she must because she understood things like why people’s eyes might turn yellow if they eat the wrong food.

My cousin Ben had introduced me to the music of Weird Al in 1986, when I was seven years old. I didn’t get the original references from his parodies, but I knew the music was brilliant and dove into his oeuvre until I figured out what every Polka Medley was referencing. Everyone else loved the New Kids on the Block, but I loved Weird Al. We rented “The Compleat Al” and our local video store, Home Video Plus, had to put in a special order just to get it to Glen Rock.

On the Rosh Hashanah before I turned my eight, my dad made a grand announcement at dinner. My dad does this thing where he settles in and shakes his shoulders back and forth when he has important news. “There’s a concert,” he said. “Weird Al is opening for the Monkees at Great Adventure. We’re going.” While Weird Al was my longterm favorite, I was recently obsessed with the Monkees. Due to pop cultural reasons beyond my childhood ken, the Monkees were experiencing a major renaissance around that time, and they were the only tapes we listened to on family car rides. I even had my first sexual fantasies about the Monkees — first Micky Dolenz and then Mike Nesmith.

It was our first family amusement park outing. We got to the arena early — it was right behind the Teepee that sold goods partially pertaining to the Indigenous Peoples that no longer exists because it’s totally offensive. We looked around. “Everyone else is here for the Monkees,” dad said. “But we’re a Weird Al family.”

Weird Al opened the show and danced with giant Mister Potato Heads while singing “Addicted to Spuds.” There were costume changes and props and accordions and medleys and songs we’d never heard before like, “It’s Still Billy Joel To Me.” We cheered for his drummer, Jon “Bermuda” Schwartz, since he was a Schwartz like us. Then the Monkees took the stage (minus Michael Nesmith, who was still being a Liquid Paper heir and refusing to join the band). They played all of their old hits and two of their newest songs: “Heart and Soul” and “That Was Then, This Is Now.” Davy Jones changed into a dress for a few numbers and pretended to be a woman, but Peter Tork wore a red shirt and white pants and was the coolest man I’d ever seen.

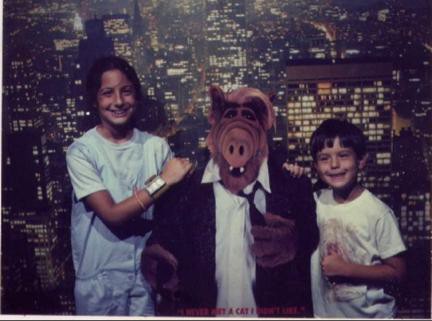

After the show, we rode the non-scary rides and took a photo with our arms around a cardboard cut-out of Alf; please note that I am wearing a hand-me-down lilac jumper and my mom’s giant digital watch. As we headed towards the exit, my dad said “hey” to someone. (My dad is not Mister Social; my mother was the schmoozer. Once she said hi to someone on the street and my dad asked who it was. “Oh, just someone I went to camp with,” she said. It was Woody Allen.) “Who was that?” we demanded. “Weird Al,” dad answered. We set off on a chase, until my mom cornered the man in a Hawaiian shirt, nerd glasses, curly hair. “Are you?” she asked. “Am I who?” the man said. It was HIM. We told him how much we loved him and how we knew every single one of his songs and how we watched “The Compleat Al” at least once a week. My mom shoved me gently. “Sing him your songs,” she said.

I had started writing parodies as soon as I learned about the concept. I was regularly tormented by girls in third grade who told me I looked like a boy and was the ugliest girl in the class, so I made parodies of the songs they loved the most — everything by Tiffany and Debbie Gibson and the New Kids on the Block. Sometimes my mom would help; I’d come home and cry and then she’d ask what songs the popular girls liked and we’d sit down and write parodies.

I stared at the ground because I was afraid of locking eyes with Weird Al and sang my parody of “Stand By Me,” called “Stand By Please,” which was about calling customer service. Weird Al said my songs were good and shook my hand and I vowed I would never wash it again, but I think my mom made me take a bath the next day. I tried to keep that hand out of the water but it was really tough.

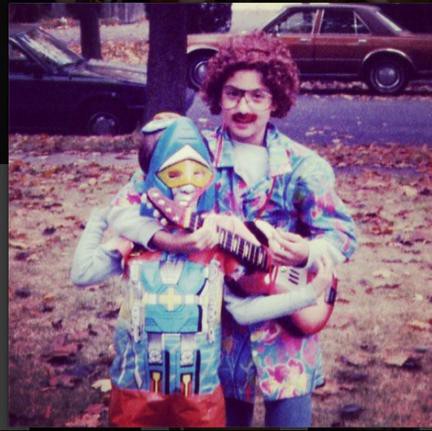

The following Halloween; I have a toy guitar because we did not own a toy accordion.

Smashcut to next summer, when I spent four weeks at Jew camp where I was desperately homesick. I cried every day. I didn’t speak Hebrew as well as the kids who went to Jewish day schools; I didn’t know the prayers; I hated going to kitah; and the lake was cold and scary and deep. Then I got strep throat and was stuck in the Marp, which is what we called the camp infirmary. There were nice nurses and mean nurses and a woman who we called the Marp Monster, a giantess who drove a van around camp sitting in the passenger seat because she couldn’t fit behind the steering wheel. The girls from Long Island were all richer than us and they wore fancy clothes like Hot Doggers and Cavariccis and I didn’t know that it wasn’t cool to pull your socks all the way up your shins and so I did that every single day because my socks felt better that way.

The Marp released me on the night of the talent show, and for some insane reason I decided I was going to get on stage and perform a medley of all my parodies to prove that I was more than just the girl with the weird sock thing who cried all the time. I sang — a capella, of course — all of my songs: “I Think We Will Moan Now,” which was a parody of Tiffany’s “I Think We’re Alone Now”; a parody of Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven Is A Place on Earth” that started out, “Ooooh baby is there anything worse / than taking a ride in a big black hearse”; and several others, including a version of “Ticket to Ride” that was about barfing all over a slide. I was a hit; everyone applauded. After the talent show, everyone asked how I wrote all those songs and I proudly told them that when I grew up, I wanted to be the female Weird Al.

I got home from camp and told my mom that I felt really awesome when I was on stage. “You’ve got the bug,” she said. My great-grandfather was an actor in Russia and started a Bolshevik theater troupe when he moved to America, so apparently this performing thing was in my blood. My mom signed me up for acting and dancing lessons. I was all set; I belonged on stage, I just knew it.

Slow, deliberate dissolve to my life after college: I graduated with a double major in English and Theater, with a focus on directing. I also spent a stint in London doing performance art. I changed my name from Becky to Bex and became a weirdo downtown performer. I did stand up comedy, I performed in a weekly midnight show called “Grindhouse A Go Go” and started singing parodies again. I went through a phase where I used to do puppet shows with my breasts where I would perform a parody of Fischer-Spooner’s “Emerge.” I was protesting the hoopla over the Janet Jackson wardrobe malfunction. I’m sorry. All of this led to a job at VH1, where I wrote dozens and dozens of parodies for various promo campaigns. That was my greatest trick — I could write a Weird Al-style parody in minutes. After twelve years, I left VH1 to become the creative director of TeenNick. My office is next to Nick Cannon’s. (No, I’ve never met Mariah.) We shoot a lot of stuff in Nick’s office: our video countdown show TeenNick Top 10 and lots of liners for Nick Radio.

On Monday, I ran out around 3 p.m. to get a salad, because that is usually the only time I can grab some lunchfood. When I got back, Weird Al and two of his people were waiting in my elevator bank. He got into an elevator and I followed him. His people (manager, publicist, hairstylist? let’s just presume) pressed the button for forty, my floor. I was determined to keep my cool. I’ve worked with people like Paula Abdul and Hulk Hogan and Danny Bonaduce and Scott Baio; I don’t get starstruck and I never gush like a fangirl. Until I tapped Weird Al on the shoulder and told him that I was his biggest fan and his new video for “Tacky” was perfection and that I met him once when I was eight years old and that he had totally changed my life.

He asked when we met. “At Great Adventure! You opened for the Monkees! And then my dad said hi to you and my mom tracked you down and then I sang you all my parodies and I was a shy little girl wearing a lilac romper!” I squealed. “Ah, 1987,” he said. I kept talking and told him about how I still write parodies for my job to this day and that I think about his music all the time and how much it meant to me when I was a sad, shy, lonely little girl. I told him that I loved him so much I dressed up as him for Halloween in 1987. “Ah, the Old Al,” he said, when he still wore glasses and had short curly hair.

We got off on my floor. I was a little weepy by then. Maybe Al was, too. We hugged. His people took a photo of us to commemorate our re-meeting. Then they followed me so they could go record Nick Radio liners in Mr. Cannon’s office. While Weird Al was doing his shout outs and liners, I could hear him from my office. I printed out the photo of when I dressed up like him for Halloween and as soon as he was done, asked him to sign it. He wrote, “Stay weird. Love, Al.” We hugged again. And then I gave him a second printout to keep.

Bex Schwartz is a writer/director/producer/creative director who loves panda, cats and cats named Panda. She’s also Weird Al’s biggest fan.