Space Invaders

by Betsy Morais

Tourists are freaks. (For context: I work in Times Square.) Tourists are unnatural to the environment into which they insert themselves; they walk funny; they talk wrong. David Foster Wallace wrote (in a footnote) that to be a tourist “is to spoil, by way of sheer ontology, the very unspoiledness you are there to experience. It is to impose yourself on places that in all noneconomic ways would be better, realer, without you.” Something similar might also be said of journalists, who also insert themselves awkwardly on someone else’s turf. But the journalist, if we’re being high-minded about it, serves some civic or artistic purpose; the presence of the tourist is for the sheer sake of personal amusement. That is to say, the mission of a tourist is selfish, and with that comes a degree of indulgence — even a sense of entitlement, which maybe is necessary to function in a situation where, as a tourist, you know you don’t really belong.

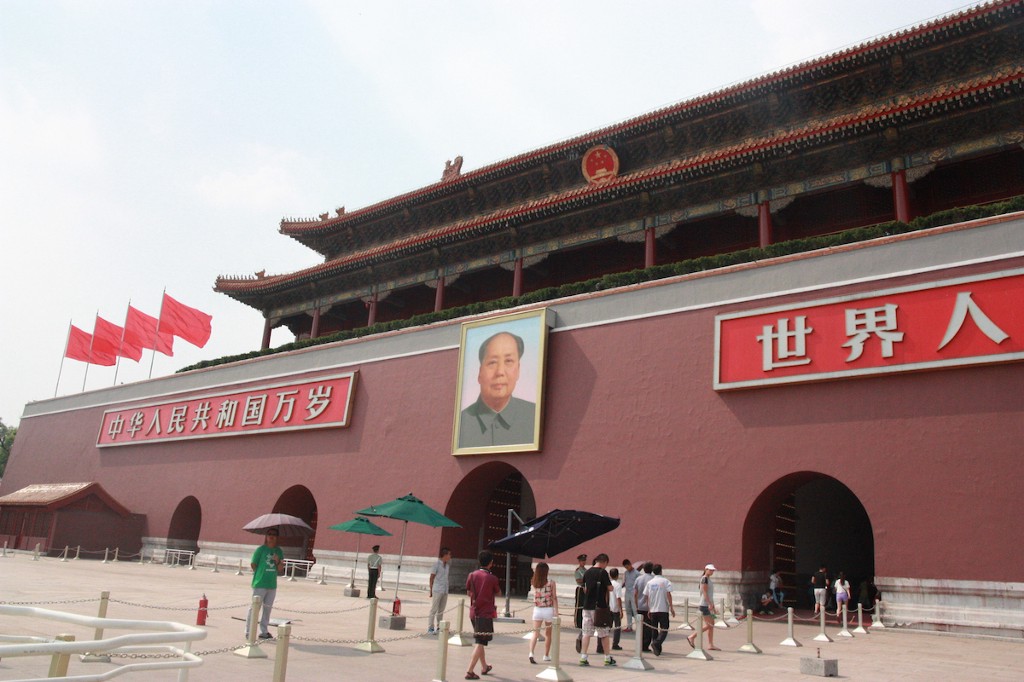

I was a tourist in China for two weeks. I bopped from one landmark to another, squeezed into the subway, and did my best to avoid restaurants patronized by anyone who looked like me (i.e., non-Asian). Being an American tourist made me a burden as well as an object of fascination. I found myself, as a novelty, the unexpected beneficiary of attention and perks: somebody in Yunnan province asked where I was from, and then requested a picture; at a hot pot place in Xi’an, where there was an hour wait for a table, my group was told, through my Chinese-speaking college friend, that we could be seated right away because we were foreigners — we were “special.” Before we could protest, the waitress whisked us to our seats — past a row of disgruntled hungry people — and gave us small plastic bags to protect our phones and a cloth with which I could wipe steam from my eyeglasses. This sort of treatment was the opposite of what I would have expected from anyone forced to serve a tourist: not only was it encouraging of our trampling all over someone else’s night out to dinner, it was downright obsequious. Tip was included, so that wasn’t a motivating factor. Awkward as this should have been, it wasn’t — tasty, fun, kid-friendly, recommended! — because that is the essential contradictory nature of the tourist.

There were also moments when my relatively harmless cultural trespassing, of a kind familiar to visitors everywhere, felt China-specific. I brushed up against an over-regulated society’s unsticky red tape, which falls away with the slightest pleading, or the smallest bribe. When there are so many rules, none can be held so firmly in place — everything is up for negotiation, if you know how to approach the transaction. My host in Beijing, a friend who grew up there, deftly navigated the complexities of requests and winks and cash offerings, because she spoke the language and she knew instinctively how to work the angles. My American Chinese-speaking friend watched in awe of her craftiness; in China, it can be difficult to know where the line is, and, yes, the closer you come to crossing it, the greater the risk of punishment, but also, the more you see how arbitrary and meaningless it is. Dancing around that line is the only way to get anywhere you really want to go. And if you are an American tourist, this makes trespassing all the more enticing.

One night, after dumplings, my friends and I went to visit the Olympic Park, built when the city hosted the games in 2008. As we approached, we saw a glowing blue rectangle, which looked at first like water droplets painted onto the black skyline. It was the National Aquatics Center, better known as the Water Cube. Michael Phelps won eight gold medals in there. We were drawn toward the bright pulsating wall, stomping ahead with determination, waving away one insistent scammer after another, all trying to make a buck by taking our picture. “You must do it now, before they shut the lights off!” one shouted. We shook our heads. But as we neared the edge of the park, we realized it was nearly closing time. A second after I got the critical iPhone shot, the lights flickered to a dim, purplish gray. But then it turned yellow, and gray again, and returned to blue, as if the cube hadn’t given up on us yet. Another salesman appeared, offering a photograph. We asked if he could get us inside. The Beijinger went several rounds with him, as he gesticulated toward a part of the fence hidden by a bush. If we gave him eighty yuan, he’d get us in the park. The Beijinger talked him down to forty. He nodded, led us around a corner, lifted back the bush, and loosened a tall grated gate with a shorter fence behind it. We climbed over the short fence, and then a second, and there we stood, basking in the blue light. It flickered again. We followed a path around the side of the building, toward a wide courtyard, where there were still vendors selling trinkets — a soldier that crawled while holding a Chinese flag, a neon top that leapt in the air. There, we faced Beijing National Stadium, or the Bird’s Nest, as it’s known. It is a magnificent modern structure, a deconstructed stadium hive with steel beams swirling around. It was designed by the Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, with artistic consultation from Ai Weiwei. Lit against the darkness, it looked like the path of wind around a spinning ribbon. We stared up at it admiringly, took pictures, and slowly gravitated toward the entrance. As we did, the lights went out all across the park. Only one overhead lamp was on — just enough to for people to see their way out.

We didn’t move. The Bird’s Nest was closed off by a gate that met in the middle by a rolling divider. It wasn’t locked. Behind it, sitting in a folding chair pushed up against the exterior wall, was a man in black, his head down, in shadow. The other non-Chinese speaker among us leaned on the divider, easily pushing it ajar. He grinned. He stepped through, and began to walk towards the man, who did not acknowledge him. Finally, the Beijinger called out, in Chinese, “Excuse me, sir?” The man looked up. He rose from the chair and approached us, saying, “you are not allowed to be here.” But as he said so, he didn’t move the divider. And he didn’t say another word as we each passed through it. He just shrugged, and returned to his post. We walked through the front door, which was open. On either side was a parking lot; straight ahead, the escalator was running. Without saying a word, we got on. First floor, second, until we reached a landing. There, in a room with rows of movie-theater seats, a man was taking a nap. We entered and saw, to our right, a door to the stadium seats. The man was roused from his slumber. “You are not supposed to be here,” he said, matter-of-factly. The Beijinger smiled at him and pointed to us, her American friends, saying in Chinese, “They have come such a long way, and they will be so disappointed if they cannot go inside.” Her expression was a little shy, a little flirtatious, totally unthreatening. The man nodded. We continued through the door. There we saw, with the lights still on, the the green Olympic turf. Aside from a few building staffers sprawled out at the corner of the track, we were the only people inside. We looked out from the center of the field at the empty stadium — with some eighty thousand vacant red seats — and waited for the police to come barreling in to arrest us.

But the security officers never came. No one bothered us. We stood in peace, taking photos and laughing in disbelief at our luck. The Americans did, at any rate. The Beijinger said she wasn’t shocked in the least. “There are rules and you are meant to push them as far as you can go,” she said. Nobody minds until they mind, and you won’t know if someone minds until they come for you with handcuffs. If they don’t, the guards couldn’t care less — and why should they? They’ve got to sit around all night with nothing to do. We couldn’t post our excitement to Twitter (blocked) or Facebook (blocked) but, when we tried to imagine what would have resulted from a similar attempt at Yankee stadium, we scoffed at the absurdity of such an idea.

A few days passed. We went to the Great Wall, to one of the “wild” parts that has not been renovated by the Chinese government and hence is not open to tourists. (We got there via a guy named Mr. Chen, known by one of the Beijinger’s adventurous friends.) The word “authentic” was thrown around as we climbed across. Five hours later, when Mr. Chen dropped us back at the edge of the city after a long trek, we were sweaty and covered in dirt. We entered the subway, bought our tickets, and began to make our way down, but two security officers stopped us. They shouted something at my Chinese-American friend, assuming he had a Chinese identification card. The Beijinger tried to explain the situation, but they shouted more, demanding to see our passports. We didn’t have them with us, so we handed over our drivers licenses. Two were from New Jersey, one was from Massachusetts; they don’t look that similar. Not that the Chinese police would know the difference. The two men (one of them, I noticed, was wearing Birkenstocks) inspected the I.D.’s and gave me a feeling I hadn’t had since I tried to enter a bar during my sophomore year of college. I stood frozen for a couple minutes, fearing this would be the end of my trip — that this was the result of my recklessness at the Olympic Park, that I had crossed the line from tourist to a pawn in some diplomatic revenge plot. And then, without looking in my direction, the officers returned our I.D.’s and grumbled something to my Chinese-American friend. I was flustered and angry. “Why did that just happen?” I wanted to know. The Beijinger led us off. “They just need to prove that they are doing something,” she said. “For the cameras.” For that, I couldn’t blame them. There was a ring of familiarity in that, for the tourist.

Betsy Morais is on the editorial staff of the New Yorker.