A Novel for the End of the (Publishing) World

by Rumaan Alam

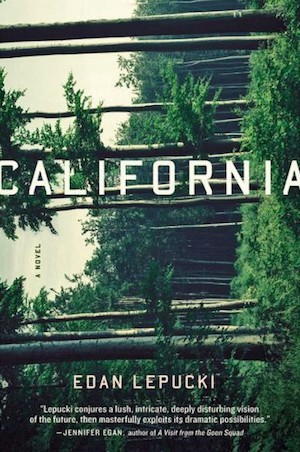

Edan Lepucki’s novel, California, will launch next week as one of the most pre-ordered debuts in the history of the publisher Little, Brown. It has become, in recent weeks, an unintentional emblem of the war that Amazon is currently waging on Little, Brown’s parent company, Hachette, as the focus of a campaign by Stephen Colbert to “not lick [Amazon’s] monopoly boot” by pre-ordering it from independent bookstores. In some ways, it’s a fitting choice, since it tells the story of a couple, Frida and Cal, making their way in the world after the collapse of society as we know it. But it’s about much more — love, marriage, terrorism, power, and parenthood.

Lepucki and I knew one another as college students, and we spoke at length about the weirdness of the publishing business, the gender politics of balancing life with being a writer, the burdens of genre fiction, envy, and more.

Marketing has to simplify something so the audience can make a snap judgment. California is a book about the end of the world, yes, but it also isn’t — it’s about family and romance and sex and domestic relationships. Have you found that discomforting, to see the book be, of necessity, turned into a product?

I would say yes and no. I think any kind of book that you write and get published is such a mindfuck. My book took three years to write, I wrote all of it alone in a room, and then suddenly people I don’t know are reading it, it has a cover. That the book becomes something consumed in any regard is both thrilling and totally terrifying to me. At this point I’m so used to the way that the book has been packaged that it doesn’t really bother me anymore — not that it’s ever bothered me, but it doesn’t have the same effect on me as it did at first, this idea of a book as a product versus a book as a world that you were living with for so long.

I was telling a friend about feeling so weird about doing publicity, and feeling it’s like you said — everything sort of distilled into one or two sentences which do not really capture the book itself. And she said to me, “You need that to find readers, and then the readers open up the book again.” Like the book becomes a world once more, as it was for the writer, as soon as they start reading it. That made me feel a lot better and I kind of, I was at peace with it at that point. But writing fiction and publicizing fiction — they’re so at odds with one another.

How do you mean?

When you’re writing something, you don’t want to get in your mind like, “What should the jacket copy for this book be? Or what would the cover be? Who would we ask to blurb this one?” When you’re working on a book, I feel like you only want limitless possibilities. You don’t want to think about the outside world.

In California you use this idea that exists so much in the popular culture — of the end of the world — while bending it into a more literary shape. Did that scare you, did that freak you out, were you like, “I’m not a genre writer?”

It’s funny when people ask me questions that suggest that I actually knew what I was doing at any point in the process, which I didn’t. When I started the book, I was aware that there are books about the future, and that are “post-apocalyptic,” but they weren’t really a presence in my writing process.

As the book came along, I made a conscious decision to not read any books that were in the same genre, because I was afraid that I would then become a copycat rather than following my own instincts. One of my favorite books is The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, but that’s probably the extent of my knowledge of the post-apocalyptic genre; that doesn’t really count as post-apocalyptic, but it’s dystopian I suppose.

I actually think I benefited from the fact that the books that I read and love are usually books just about people, literary fiction that isn’t really premise-oriented. I think that gave me some freedom. When I sold the novel the contract said “suspense novel” and I was totally surprised.

Using the term genre is often coded way of saying a book is stupid, or for a stupid reader. California made me think of The Secret History; a literary book that happens to be a ripping yarn. I don’t know at what point those two became at odds with one another. Why is your book called California?

It was originally called Land, as in the verb and the noun. But I knew all along that that was a very uninteresting title. My agent sent all these different words and phrases from my book, and California was one of them and I immediately loved it.

For me, it has multiple meanings. One, they never say where they are, and so I sort of love the idea of a book being the name of the place where they are, even though in the books themselves they don’t say where they are. Cal is the husband and sometimes people called him “California” in college, which was sort of an idyllic time for him. And overall there’s the sense of like this place that they used to know and used to inhabit, that way for freedom and childhood.

So I love that resonance. And then, I feel like California is the first for a lot of things. I know New York, blah, blah — but we have cool fashion, avocado on sandwiches, and of course the end of the world will occur in California, I’m pretty sure.

We have this idea of the writer as like the lone genius, which may be true, but the writer has to give her work to a corporation and an editor and an agent and all these other people are involved in the making of this product. Even down to choosing its title.

I don’t think I’m a lone genius. I’m extremely grateful, one, that they paid me money for something that I did, basically would do again for free, that I was doing for free forever, and that they were so passionate about the book. And every discussion that we had I was included. And so even the cover, my editor and I talked about images that we liked. I felt like I was part of the conversation. I remember when I got my first editorial letter, it was like ten pages long, single-spaced. And I had a little bit of a freak out. But it wasn’t so much like, “This corporation is trying to like make my book into something it’s not.” It’s more that I had been running classes and workshops for years since graduation from Iowa, but I actually hadn’t done workshops since 2006. So it was a good seven years that someone actually had like laid down the law with me.

It also helped that when I sold the book I talked to a couple editors and they all had pretty much the same suggestions. They’re all extremely sharp, smart readers and so I never really felt like they were like, “Well let’s make it more like this so we can make a lot of money.” It felt more like a workshop discussion rather than a marketplace discussion. And I think that a lot of times those can be in concert, they don’t necessarily have to be at odds with each other.

I think of Jonathan Franzen, when The Corrections was picked for Oprah’s book club and part of what he said was his concern was having Oprah’s logo on the jacket of the book. But the FSG logo is on the cover too. If your book is so precious to you, then you should just take it to Kinko’s and have it printed and hand it out on the street corner.

People always make fun of Oprah, but she picks a lot of terrific books. I think it’s the idea that a lot of women are reading a single book that makes people uncomfortable, because they feel like that means it’s a stupid book. That idea like, “Oh, my mom read it.” Well you know what? I’m a mom and I take offense at that. Like yeah, a woman who has children isn’t an idiot. So I feel like it’s definitely a gender discussion.

I want to ask you this question, though I ask myself if I would ask a man the same question. I hope I would. You wrote this book for three years, you have a three-year-old son, how on Earth do you balance those?

I wrote half of the book before he was born. I found pregnancy helped me with deadlines. It was like, “I have to get this number of pages done before I give birth.” We had free childcare from my mom the first year of his life, and I had a babysitter that I paid. So I had like 12 or 15 hours a week, as soon as he was like six weeks old. And I was able to write at my neighbor’s apartment, which was just a godsend. So I could write for two hours, come back in, nurse my son, go back and do my work.

Raising a child, making sure you raise a human being who’s not a total jerk, is very difficult and an important, significant task. But the day-to-day raising of a child is so mundane to me. I just don’t think that I could be that kind of mom, maybe because I already have another task that I want to do every day, which is writing books.

So I really struggle with it, because some women take their kid to daycare and they’ll say, “Oh, if I could stay home I would.” But the truth is that I love to work. I really like it.

Do you feel like that weighs on you differently because you’re a woman?

I don’t know, probably. Nobody ever faults a man for going back to work after their kid is born.

I guess it’s vindicating to have actually sold a book. Let’s say you had some friend or some fellow daycare mom who was like, “Oh, I can’t believe Edan uses daycare and then she just goes and sits at her computer all day. How lucky for her.” To actually then be able to say, “I got a paycheck,” really changes the nature of that conversation, fairly or unfairly.

Why not? Why can’t a kid go off and be with other children for some of the

day every day? Like why do we have to make money in order to make that be okay?

Maybe I ask about this because the book is very concerned with parenthood and childhood. A key point is this question of whether or not it’s ethical or moral to have children, given what’s happened in the world. But what is the subject of the book, in your estimation?

I think marriage is what the book is about to me. But I would also say in concert with that, there is this question of parenthood because obviously I was either wanting to be pregnant, pregnant, or had a new baby when I was writing the book. So that was obviously on my mind. There are things that are really reprehensible in the book, but I don’t necessarily think the idea of not having any children is a horrible idea. Because that makes a lot of rational sense in the world that they’re in.

I remember that soon after I had given birth all I really wanted was to be a child again. When you haven’t slept in 24 hours, that desire just to have someone tuck you in felt very real to me.

The book to me was sort unrelentingly dark for a long time, and then it ends sort of remarkably optimistically.

Interesting. Some people think it’s like a horrible, dark, dark ending.

I felt like it was a very uplifting ending. I felt better anyway.

I had a vision of the very end. That image came to me way before. I’m really interested in the way that, when people have children, they become different in their motivations. So you might give up certain freedoms in order to be safe with the child.

If you strip away the metaphor of dystopia then what you’re offering is a very dark view of marriage and relationships.

I really don’t know. You should ask a book club what they think.

Every generation always feels like it’s the last. Do you truly think we’re fucked, or were you just telling a great story?

I feel it both ways. I remember when I was just pregnant and nobody knew and I went to a book club about the book Freedom, and in that book there’s talk of being childless by choice and overpopulation. I remember going on this rant about how we were so fucked, and this makes total sense. And one woman said, “You obviously aren’t having children.” I was pregnant at the time but I couldn’t say anything.

We don’t know if we’re going to have another child for various reasons. But sometimes we’re like, “Should we have another child? Maybe he needs someone to cuddle when there’s really no oil and it’s going to be horrible, and they need to be together.” We actually go there, because I think that’s a very real possibility. Sometimes there’s another part of me that thinks, “A lot of beautiful, wonderful things have happened in the last hundred years so we could maybe get it together.” But for instance, I do think the energy crisis is going to be an even more real horrifying thing in the next hundred years. I rehearse those fantasies and nightmares like everyone else. But I think, like you said, every generation thinks they’re coming to the end.

Having a kid is just a way of shoring up against the future anyway.

True.

Maybe no one would ask you these questions if you were a dude. The idea of the missing child or the child in peril exists in the book as like a sort of primal fear but it largely happens off of the page.

Yeah, and I will be the first to say that I think the book could have been much darker.

God, I don’t know dude. I don’t know if you could have read it if it were. What are you writing now?

I have like 150 pages of a new novel that takes place in our contemporary time. It’s about women, that’s all I’ll say.

Do you feel a need to do something really different?

I felt like California was really different. It felt unlike me in some ways because of the subject, even though the tone and I suppose the language was the same. So actually going back to this new book I’m writing, it’s more in line with my novella in terms of tone and humor.

Did spending $50,000 or whatever on a graduate degree feel worth it to you in the balance of it?

I went to Iowa for free, and I urge everyone to go to graduate school for as much funding as they can possibly get. I feel like I got a great education. I always say it’s not a lucrative business, or it can be but you don’t know if it’s going to be, so don’t tie your writing to money. If you can, try not to. I’m really glad I went to Iowa for a number of reasons. I feel like I did learn a lot, I also went when I was 24 and I wasn’t a bad writer but I was really inexperienced. Thinking about my writing life now, my practice of writing, and all that kind of stuff since then, I hardly wrote at all when I went there. And I had hardly written any stories, I had written maybe three stories in two year, and I just didn’t know a lot of stuff.

But that was also only two years and that’s a short time in the life of a writer. I graduated in 2006, so it will be ten years that I entered Iowa this September so that just feels like so long ago. I’ve written a novella and I wrote a novel that didn’t sell, and California. Even though I did learn a lot, all of my novel writing happened after Iowa. So everything I’ve learned about novel writing, I’ve learned from teaching other novelists. The conversations that I have with my novel students continually teach me about the form.

Let’s talk about envy. My response when I heard about your book was envy. Then, I read it, and I really liked it, and it made me feel, strangely, better. But I always feel so jealous of other writers.

Yeah, for sure. It’s kind of like how people who are trying to get pregnant can’t stand pregnant people, or going to baby showers. There was a time I kept seeing all these bios and I’d say, “This person went to Iowa after me?” And I would just get so annoyed and I would just throw whatever across the room.

But I didn’t know them, and I knew that it was a totally petty feeling, so I didn’t really give into it too much. I recognize that that’s completely human to feel that way.

I’m not too hard on myself. In one episode of Louie, Louis C.K said something like, “You know you’re in love when you can be racist.” It’s sort of like that, like you have a designated person where you can be like, “I don’t like this person because they got what I wanted.” And it doesn’t leave your bedroom or kitchen, and it doesn’t mean you actually feel it, it’s just sort of like an ugly human thing. But I always try to balance it with supporting people, and buying their books, and doing all those things. Because it’s like if somebody feels hateful towards me, like, hey, they can do that, but I hope they still buy my book because I love it.

I think it’s something people are scared to talk about. The cheeriness of the literary culture, I don’t know if it’s a problem or not, but it doesn’t really dovetail with what I think writers carry around inside of them.

Don’t you think that both sides are exacerbated by the Internet? Right now my Facebook is nothing but my child and “Hey, look at my book.” I don’t care. This is my time to be excited.

Of course. I don’t think you should stop.

But you just see everyone’s news all the time — you may feel bitterness privately but publicly all you see is the cheering. What do you think?

I have had to set aside my feelings of rage. I was talking to Emma [Straub] last summer about this question and she said, you just have to actually do your work. And I think that’s really true. I think Emma in particular, she takes it on the chin from a lot of people because she’s so vocal and now she’s so successful.

And she gets a lot of shit.

But I think what you can’t take away from her is the fact that she actually did the work.

One thing about Emma is that everyone thinks she’s so nice, and she is so nice, but you clearly have not had dinner with Emma because . . .

She’s a real human being. It’s easy to give into envy and it’s a lot harder to stay up until one o’clock in the morning writing.

Yeah, exactly. When I am writing, I don’t check my email even. I don’t go on the Internet at all. The only thing is me and my brain trying to shut out the noise and work.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

California is .