Death of a Mr. Dream

by Kevin Lincoln

The first Mr. Dream show was on Halloween night, 2008 in a New York City apartment.

Adam Moerder, Matt Morello, and Nick Sylvester dressed up as Dhalsim from Street Fighter, Daniel Day-Lewis and “the Karate Kid [after] letting himself go (concept costume),” respectively, and played to a room that included “two furious girls who kept trying to dance and failing, since you can’t really dance to a band that sounds like Nirvana, or the Wipers.” Over the next five years the band would go on to release a few EPs and an LP; tour with Archers of Loaf, Sleigh Bells, CSS, and Cloud Nothings; and sing in the chorus at LCD Soundsystem’s final show.

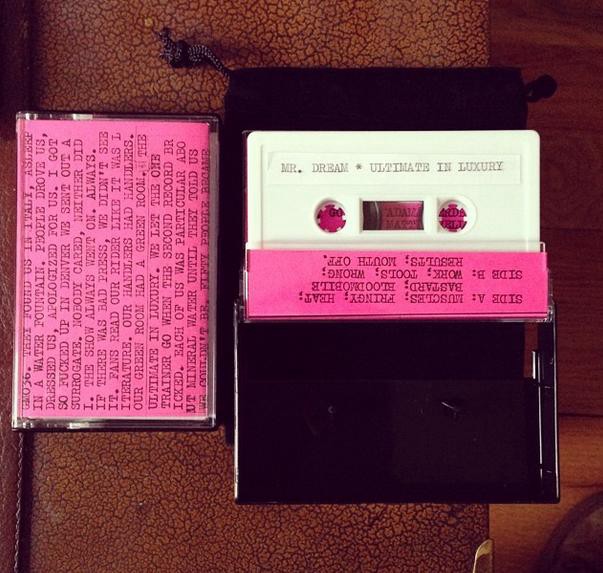

On Monday, the band released its final, posthumous album, “Ultimate In Luxury,” which you can stream here. Sylvester and Moerder are both friends, so I reached out to do a little postmortem for Mr. Dream and the handful of scorched-earth punk records they left behind.

So tell me about the birth of Mr. Dream. You two have known each other since college, right? What led to starting the band?

Nick Sylvester: Five years ago I would have said something like “pure and utter disgust for chillwave.” The truth is more banal. I knew Adam from the Lampoon, and I knew Matt through a mutual friend named Win Ruml. The three of us were all looking to make music at around the same time in 2008. We went to a Jay Reatard show together at Europa and knew that was the kind of music we needed to be making: something loud and fast and stripped down. It looked like a lot of fun to play that kind of music.

I would describe Mr. Dream’s music as sort of hyperkinetic lit-punk, or like, the sound of pissed-off New Yorkers playing music that sounds like F-18s. Please improve on this description.

NS: That was always the blessing and the curse of this band. People heard we went to Harvard or wrote for Pitchfork and assumed the music was much more deliberate than it actually was. I don’t recall any literary references in any of our songs.

AM: I like to think that Mr. Dream’s sound predicted the pummeling rage and anguish one finds on Twitter.com every day.

Though I’d read your music writing before I’d met you, this is the first band I know of that you two were in. How long have you guys been playing?

NS: I played trumpet in a wedding band called the Stu Weitz Orchestra. We had one or two gigs every weekend around Philly. I also played trumpet in the Matt Turowski Jazz Explosion. This is how I paid for high school. In college, I was in a band called Forced Premise with a bunch of Lampoon people: Simon Rich, Rob Dubbin, Colin Jost, and sometimes our friend Matt LeMay. He was an honorary member.

Adam Moerder: I was in a grunge band in high school, but we never made it further than the high school talent show circuit. The band was called Scorched Earth and we had a rule to always perform in our pajamas.

NS: This is the first time I’m hearing about the pajamas.

How’d the band go about writing songs?

NS: We all tried to bring in rough ideas, but it was usually Adam who brought in the strongest ones and stitched the songs together. I learned so much about songwriting from him. He might be my favorite rock songwriter — which made producing these records so difficult and emotionally complicated. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t want to fuck anything up. Our first EP was the first time I ever recorded or mixed anything and I made all kinds of stupid mistakes. So the kind of sound we were looking for changed as I learned new tricks and got better at listening. There aren’t many bands I know of whose production gets better with each successive record — certainly not in such a pronounced and obvious way.

Why’d you guys decide to end the band?

AM: There was this big swath of music we loved that wouldn’t have worked in the context of Mr. Dream. We wanted to branch out, but felt restricted by how a Mr. Dream song was “supposed to sound.” Plus we were gradually becoming not terrible at our instruments, which opened up a lot of possibilities.

Nick, how did the evolution of your record label, Godmode, coincide with the lifespan of Mr. Dream?

NS: Godmode was a vanity label for Mr. Dream releases. In 2011, I started doing more production work outside the band, and one of the acts I worked with was YVETTE. We did a 7” together (Matt LeMay co-produced), and not a single label we approached would put it out. I couldn’t believe it. I had just assumed all great bands find a home somewhere eventually. Not the case. I decided to make Godmode more of a real thing and put out the record.

AM: I don’t have an official title on the label (other than Montreal Sex Machine and FITNESS member), but I generally try to pitch in whenever possible, whether that’s listening to drafts of songs, loading in gear for a show, or buying some Red Bulls for Nick because he says it’s very important for the label that he has Red Bulls.

NS: We can work on an official title.

AM: “Riff technician.”

So why does Godmode release its music on cassettes?

NS: The process for making the music isn’t different, but the mindset is. I wrote about this for Pitchfork last year, you can read that here:

But there’s no format more human than the cassette. No format wears our stain better. I have not encountered a technology for recorded music whose physics are better suited for fostering the kind of deep and personal relationships people can have to music, and with each other through music. … No audio format keeps me more focused on listening to the thing itself, without the distraction of having a web browser right in front of me, without the baggage of an ersatz music news cycle, the context upon context, the games of the industry. Music released on cassettes doesn’t feel desperate or needy or Possibly Important. It tends not to be concerned about The Conversation. It resists other people’s meaning. That’s what I like about the cassette. It whittles down our interactions with music to something bare and essential: Two people, sometimes more, trying to feel slightly less alone.

One of my favorite touches about Godmode are the essays that you guys include with the cassettes, which are like abstract liner-notes. How’d that become a thing, and what do you guys like about it?

NS: I started doing this when I found out other tape labels were copying our style guide — right down to the type and stamp. It’s not exactly an original idea to use stamps — I ripped off Jon Galkin at DFA — but after I found out about this, I wanted to do something nobody else could replicate. The cover essays are a way to vibe a release and give the songs an emotional context.

AM: The packaging was a stroke of genius from Nick. The essays are my favorite, they really set the tone for each release. As a kid I remember being so excited to buy No Code, the Pearl Jam album, because the CD packaging included all these random polaroid pictures (one was an extreme close-up of Dennis Rodman’s eyeball). What does it all mean?! It created such a cool aura of mystery. While nothing on Godmode will ever measure up to the divine perfection of Pearl Jam, we’re at least standing on the shoulders of giants.

The Godmode family now includes Mr. Dream kindred-spirits Sleepies as well as artists completely different from your band, and each other, like Yvette, Fasano, and Shamir. What’s the pattern usually like of an artist ending up on Godmode?

NS: I’m trying to put together a good cocktail party. For me, that means playing personalities off one another. You end up approaching something like Shamir’s music in a very different way when it’s on a label with Yvette. The only hard rule for our crew is no assholes. I work with every artist really closely so I have to want to actually spend time with you.

Nick, what kind of trajectory do you see Godmode taking? How are you looking to expand and continue the label?

NS: It’s a new operation so there’s not much of a plan beyond doing more of what interests us and less of what doesn’t. I enjoy every aspect of Godmode. Everything from how we reply to press inquiries to how we do our distribution to how we do our books is an opportunity to do something special. As a producer I’m lucky: I get to choose what I want to work on, and feel as invested in the music as the artists do.

Adam, what are you interested in these days, making-music-wise? I feel like I read somewhere that you were sort of over, or frustrated with, guitars?

AM: Oh, I still love guitars, but I felt uncomfortable being pegged as a “rawk” guy. It’s like that Seinfeld episode where Jerry’s afraid to have a threesome and forever be known as an orgy guy…that lifestyle becomes you.

Enter MSM and FITNESS. With the former, Nick and I really wanted to capture a rock band attempting to make dance music and the rickety mess that ensues. It keeps getting compared to LCD Soundsystem, which is fair, but the inspiration mostly came from those Rolling Stones records where they tried to do disco.

FITNESS is mostly the result of me learning how to use synthesizers and drum machines. It’s a totally different writing process than anything else I’ve worked on, which is really refreshening. Basically the project was born when I first laid eyes on this album cover.

I remember you tweeted something about a Pitchfork interview with the band Posse and how it was cool that musicians were talking about their day-jobs now. You have a day job; Adam and I worked together at BuzzFeed right before I left, while Nick has done a bunch of interesting stuff outside of music. What has it been like balancing music with working, writing, etc.?

NS: I don’t think anybody deserves to make a living from music. If it happens, that’s great. But you can’t expect people to like what you do, let alone pay for it.

Kevin Lincoln is a writer living in Los Angeles.