Voicemails From The Terrifying Future

In 2022, fires will destroy over 2,025 acres of Texas. In 2048, the Glacier Land Resort will open for people looking to see what life was like before the glaciers melted. In 2049, the Smithsonian — no longer open to the public — will feature a preserved hummingbird in their archives, the last proof of their species ever existing.

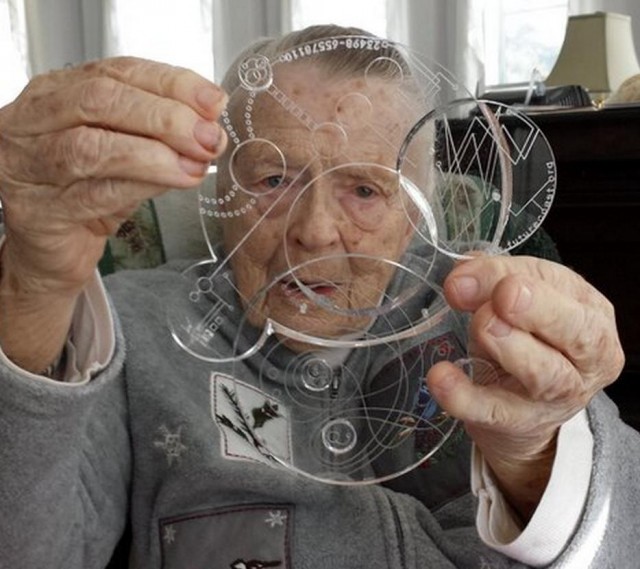

These are all possible futures as created by the users of FutureCoast, an interactive alternate reality game that began in February and concludes its run in May. Funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation, the overarching story of the game is simple: Mysterious objects known as “chronofacts” have begun appearing throughout the world. Once decoded — which a grassroots organization luckily takes care of for us — they’re revealed to be voicemail leaks from the future, and not necessarily all from the same one. And that’s, well, that’s pretty much it as far as the plot goes.

But while the story is simplistic, the project — produced by Ken Eklund (who previously tried to save our doomed planet with the award-winning ARG World Without Oil) and Sara Thacher (one of the main forces behind San Francisco’s Jejune Institute ARG/public art-ish thing) — is anything but. More than simply a collection of possible “what-ifs,” the true goal is figuring out how to use storytelling to persuade.

Rick Paulas: There’s a lot of different mediums you could have chosen for this project. Why just voicemails?

Ken Eklund: I wanted to focus on what the medium was. Because if we’re like, well, we’re getting videos from the future, it really opens up this big can of worms creatively. That could be a successful thing, “the YouTube of the Future has a leak in it and we’re getting videos.” But you could see how that could pre-select for people who are really good at doing videos. It becomes this narrow range who could participate and get above the bar that was set. I wasn’t really interested in getting high quality from a narrow group of people. I thought it was very important to make it very democratic. It is a communication medium anyone can do.

Sara Thacher: Voicemails are basically these little miniature short stories, micro-stories, that give you a sense of place and story and characters. But voicemails also do this other thing. It’s a story structure that you immediately understand. I say voicemail, and you understand. It’s a message that’s left for a person and there’s a story structure all built in just by saying “voicemail.”

I was kind of shocked that, instead of the voicemails being this scary apocalyptic future, they were mostly people with everyday tones, almost banal. Did you expect to get that? Or did that come out organically?

Ken: It does organically develop. You could say there’s a certain amount of transference because of the medium of voicemails. But I really thought there’d be a bunch of voicemails from people who were in crisis, and a bunch of screaming and incoherent and apocalyptic visions. If you kind of look at what goes on in the movies, it’s always The Day After Tomorrow, or whatever the deal may be. So for me, that’s a very interesting signal.

Sara: There’s a couple of voicemails that are just screaming. They’re in there. But people who take the time to create a voicemail have a genuine desire to communicate about their vision. And you just can’t… it’s actually very difficult to scream disaster and actually give a picture of what’s going on. So people gravitate towards stories where they can be descriptive.

Were there any utopian futures you had to edit out?

Ken: We publish everything we get, so there is no editorializing. We really do want to be very receptive place. But I would say that we have indeed have utopian ones. There’s one we got called The Wind-Gen One. It’s a very simple message of a neighbor calling another neighbor and saying, “Hey, you don’t have your wind generator on, we’re thinking we’re maybe going to be in a brownout situation this weekend, and we need you to turn on your wind-gen.” So, that is a pretty utopian future. A neighbor is being neighborly and just calling and telling them what’s going on. It’s kind of strange we don’t recognize utopia when we hear it.

Sara: They can be really subtle. We had a voicemail that’s a pizzeria calling back to confirm an order, and they’re ordering pineapple pizza, and it’s their top shelf pizza. They’re making a commentary on what foods are going to be available, and the relative exclusivity and price of the foods of the future. But all in this very, very simple little voicemail.

Ken: You can spend a lot of time parsing them out into what they really mean. There can be the voicemails that sound like we have this future under control, but in the end they’re ultimately sad, because you listen to them and be like, oh, if this is true, then this is also true. The stories of greatest hope and greatest fear can be combined in the same voicemail, and it’s not obvious which it is when we’re listening.

A big part of the story is that these “chronofacts” are discovered and sent in to be decoded. But these chronofacts are, in fact, real physical items you place in the actual real world. It seems odd to spend money creating and placing these when it seems mostly unnecessary for the project. What was the thinking behind that?

Ken: It’s a lot of trouble, but it provides this kind of moment that makes the fiction seem a little more real. There is a desire that these games have. People want to live in the fiction a little bit. It doesn’t take a lot of money, it doesn’t take Hollywood actors. With as simple a thing as having these and the idea of voicemails, there’s this buy-in.

By making this a user-submitted project, you’re essentially taking a poll of what people’s feelings/worries/etc. are about the future. Did anything surprise you?

Ken: For me the biggest point of surprise was people talking about air pollution. I just don’t really flag that myself. But since the game and this theme has emerged, I’d been thinking about it, and I have my own theories about why that theme is emerging, and it has to do with China and the bad air days in Beijing. The idea that we are slaves to energy production, and the idea that if energy production necessitates us ruining our air, we will do that, because we want our energy. That’s what happened in China. They were just making these coal plants, and nobody did the math about how much air a coal fire pollutes.

So, is the goal of the project to get a sense of what people are feeling?

Ken: There certainly is an aspect of FutureCoast that’s interested in seeing what people come up with. But the game goes back to the creation of these voicemails, and what happens with people when they actually do that. When we talk about games of change and causing change, it’s really about that moment when people think about the future. They’re doing it in the context where they’re considering making a voicemail, and idly speculating on the voicemails they heard. It’s this really interesting space of future thinking where you go, this is not some kind of abstract subject, climate change and the future that we live in. This is what’s actually going on. This is a future that people I know are going to be living in. So, to see people go through this process of making voicemails, that’s where the game is actually working its change. This very simple invitation to play is actually not all that simple. It actually starts all of these gears turning, which I hope continue to turn.

Sara: When you create a voicemail, you have to put yourself in the first person. Translating from what do I think the future might be like, to what’s my first person account or communication set in that future. It causes you to think about that very differently. Even if that’s not a future you’re ever going to see, you have now used first person language and have acted as though this future is real for that brief moment. You gain this lived experience. That’s very different from “Well, I think things are going to get hotter.”

Ken: The question is, how do you convince people of things? We’re in this place right now with climate change where you can line up almost every single scientist on the planet and still people just kind of go, um, I’m just not going to take that. And so you ask yourself, what is actually wrong? How do people get persuaded of things? Where is the emotional contact?

Sara: It turns out information isn’t that useful in changing minds, or persuading them. Facts don’t actually do that very well, even if it’s a fact from a reputable source. There was a fantastic article that came out recently that looked at the issue. They said, here’s this data set. And a person’s ability to analyze the data set is directly correlated to their mathematical ability, because it’s something that requires a little bit of math. If you score well on a general math aptitude test, you’re going to do better analyzing data and using it to draw a conclusion. But once it becomes at all partisan issue — that is, it has at all a spectrum of viewpoint, where there’s actually a left and a right — that correlation between mathematical aptitude and ability to understand the same data set is not correlated at all. It’s entirely predicted by what party you associate with, rather than your mathematical aptitude. Your ability to understand factual information drops off dramatically. Actually telling stories and telling fiction with people I can relate to, and situations I can relate to on an emotional level, is much more important than the facts. And it goes both ways. This is how Fox media runs.

Ken: There’s a useful dichotomy between rhetorical and poetic means of persuasion. Rhetorical persuasion is the idea that I have an argument, someone else has an argument, and we have a winner. In the science world in particular, when they talk about persuasion, that is all they are talking about. But in the real world, there is advertising, there’s the reality that poetical arguments really have currency. When you look out of the world of science, the world actually works on poetic persuasion, on the idea of stories and competing stories. When you look at the science of persuasion, there’s been all of these studies done about rhetorical persuasion, and you have very little done about poetic persuasion. That’s one of the things we want to bring in to the science around climate change. Voicemails are this way to open up this poetic form of talking.

Rick Paulas will gladly accept the bad parts of the future, as long as it also includes self-lacing shoes.