The Boy In The Well

A 16-year-old boy who stowed away on a flight from San Jose to Maui has been referred to child protective services, which will do what it can to understand why he ran away not just from his family but to an airport, into the belly of an aircraft, across the Pacific ocean, and into the curiously long ledger of boys who climbed into the wheel wells of planes.

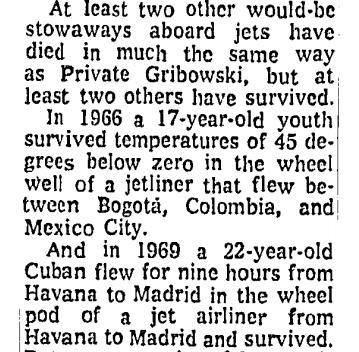

The wheel well is not a place for daredevils; nobody rides for fun. It’s usually understood by its inhabitants as a means to an end: It’s a free flight, a passage over a border, or an escape from troubles. Decade after decade people make the climb. But decade after decade these people die: In 1975, a the body of a wheel-well stowaway fell into Biscayne bay; a few years earlier, in 1972, an 18-year-old Marine Corps recruit froze while attempting to flee from San Diego to New York after reporting to his mother that he had been beaten in training; a South Vietnamese soldier attempting to escape from Da Nang to Saigon that same year perished huddled near the landing gear of a 727. These stories would serve as clear deterrents if not for reporters’ consistent habit of framing deaths as anomalies. Who doesn’t want this to be an option? From the story of the young marine:

So yes, maybe next time!

More recently, stories have remained gruesome: In 2000, a man lost concsiouness and died somewhere between Amsterdam and Newark; a stowaway who fell from the sky into a Nassau County parking lot in August of 2001 was so mangled that police could only tell the press that he was “25 to 40, had olive skin and could have been Latino, Arabic or Caucasian.” Two years later, a frozen body arrived at JFK. In 2005, the body parts of a stowaway rained down on a Long Island home. In 2010, the body of a North Carolina teenager dropped from a plane on approach to Logan International, landing in a Boston suburb. Two years later, after a body landed in the streets of London, the an investigation assured the public that the stowaway was probably dead before he fell from the plane.

Ten years ago Brendan Koerner collected data suggesting that the stowaway survival rate is around 20%, which feels high considering the clear and impossible conditions of altitude (although: shooting yourself in the head is only slightly more likely to kill you). But the data set is small, at around 70 tries in the last 60 years. And a closer look at reported success stories usually reveals something unusual about the flight, or something odd about the passenger’s story. A boy who survived a flight from Benin City to Lagos endured just 45 minutes of exposure at just 21,000 feet. A teenager who was reportedly found under a plane on a Miami runway after a wheel well flight in 1993 was arrested nearly two decades later after a lucrative career as an international jewel thief and con man. His story of his arrival in the United States is now considered less than reliable.

What we’re left with is a list of old children and young adults, almost all boys or men, few of whom are available to talk about their experiences, and most of whom undertook suicide missions that they understood to be reasonable alternatives to whatever was going on at the port of departure. “He was unconscious for the lion’s share of the flight,” the FBI told the press of this week’s stowaway, who stepped out of his plane and wandered around the tarmac for a while, soaking up the Hawaii sun, until he was collected. If we ever hear from him again, he might be able to tell us what he thought he would find in the well. But he’ll never be able to tell us what he saw.