A Conversation With Matt Taibbi and Molly Crabapple

by David Burr Gerrard

On one side of The Divide — the gap in the justice system between the rich and the poor that provides the title for Matt Taibbi’s brilliant and enraging new book — financiers and other wealthy people commit egregious crimes, including laundering drug money, and rarely face jail time. Prosecutors worry about “collateral consequences” before filing charges.

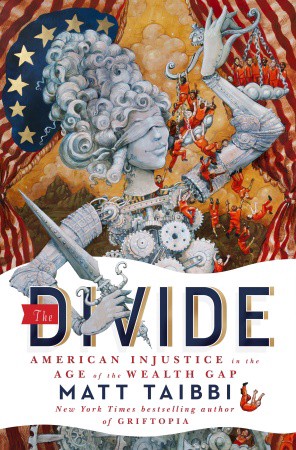

The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, by Matt Taibbi with illustrations by Molly Crabapple, will be published on Tuesday. You can order it now now now, wherever capitalism allows you to obtain books:

• Spiegel & Grau / Random House

• Powell’s

Previously in this interview series:

Discussing the labor of sex work with Melissa Gira Grant.

Returning to Marxism with Ben Kunkel.

The new story of labor unions with Micah Uetricht.

On the other side is Andrew Brown, who lives in a neighborhood obsessively monitored by police and is arrested for standing outside his own building talking to a friend. The arresting officer defines this behavior as “obstructing pedestrian traffic,” despite the fact that there are no pedestrians on the street to be obstructed. Unlike most of the horrifying anecdotes Taibbi recounts, this one has a more-or-less happy ending; when the judge learns the facts, he dismisses the case. But this dismissal happens only after Brown presses for his case to actually be heard, which surprises both the judge and Brown’s defense attorney. He is expected to accept whatever plea deal he is offered rather than contest the charges. That’s what usually happens at that point in the script.

That theater metaphor is cribbed from “The Theater of Justice,” an excellent recent piece in Vice by Molly Crabapple, who in the years since Taibbi called her “Occupy’s greatest artist” has also established herself as a stellar writer. For The Divide, she has contributed illustrations of great terror and beauty.

I recently sat down with Taibbi and Crabapple over coffee in the West Village. (Crabapple joined late.) In writing the book, Taibbi said, he consciously count down on the profanity that marked his prose when he was writing for The eXile and the New York Press, as well as much of his work at Rolling Stone. This is effective: The Divide’s calmly presented material will make any reader equipped with a basic sense of decency do the swearing themselves.

You talk about how there’s this liberal cliché of “The Two Americas.” You say that the problem goes deeper than that.

Taibbi: When people talk about the two Americas, they’re talking about a statistic. The thing that I was really struck by with this material is that very few people have personal experience on both sides. There’s a very small group of people that knows how these Wall Street cases fall apart, and how rare it is for any kind of prosecution to happen, and the people who know that are not the same people who experience stop-and-frisk or who are in jail for some bullshit thing.

This visceral difference between the two bureaucracies is much more powerful than just a number. It’s a radically different approach across the board, not just in terms of how much we pay people, but in terms of how easy or hard it is to escape prosecution. What I’m saying is that the term “Two Americas” is emotionally insufficient. It doesn’t express the breadth or horror.

You talk about how the “losers,” if you will, live under a state of constant police surveillance.

Taibbi: Not just police surveillance. Surveillance of all kinds. Think about the consequences for an ordinary person, who doesn’t have a lot of money, of missing a payment on your Gap card. That shit is going to follow you around for a while. There’s this whole matrix of bureaucracies that’s watching your every move. If you happen to live in a bad neighborhood, you might have interactions with the police once a week, or once every two weeks, whereas the person who comes from money may never have any interaction with the police. If you have a problem with your credit, the consequences are going to be much more extreme than they will be for somebody who lives in that other stratosphere. You’re being monitored in many more ways.

And it warps your mind.

Taibbi: Definitely. Everything becomes all about the police. You have to make a million calculations. Whereas I went to a prep school where kids had money and did every drug known to man, and I never saw a cop. There are guys who work here in downtown Manhattan, guys who work on Wall Street, they’re doing blow, they’re doing pills, they’re doing everything. They don’t have to worry about getting picked up and strip-searched by the police on their way home. It just doesn’t happen.

It’s two different ways of looking at the world. And, sure, that’s a cliché. The problem is that after we allow the situation to go on, it starts to feel natural. “Oh, of course, that’s where crimes are committed, so that’s where we put cops.” That’s not true. If you sent cops into the community where I grew up, you would have just as many drug arrests as you do in Bed-Stuy.

Could you talk about the process of reporting this book?

Taibbi: I kept doing these stories for Rolling Stone where nobody ever goes to jail. That’s the punchline of all of them. Then it occurred to me that you can’t tell the full ridiculousness of that story without investigating who does go to jail and why. I actually didn’t know a whole lot about that. I had to do a lot of research into how the courts work.

I followed a bunch of interesting cases and then wrote the thesis afterwards. So I wrote it kind of backwards. If I had known what I know now, I might have structured it differently and made it read a little better. But I think it worked out.

I think so, too. I’ve been doing this series on leftist books, and this is the one that made me hope for a revolution tomorrow.

Taibbi: Good. That’s sort of the reaction I’m looking for.

It’s funny. I started off trying to be a humorist, and it turns out that my ability lies in making people really upset. This topic is tailor-made for that. There’s no way to experience a lot of this material without getting really angry.

I do notice that your prose is more sedate in this book than it was a few years ago.

Taibbi: I listened to my hate mail. I think that if somebody takes the time to write you a letter — not tweet something, but if they take time to sit down and write you a letter to tell you why you suck, you should respect that and listen to it. You’re always blind to certain weaknesses.

I made a conscious effort to cut down on the profanity. There are only a couple places where it’s even in this book. And I didn’t make myself a character.

Molly Crabapple enters. After introductions, she sees my copy of the book, the first time she’s seen a finished copy.

Crabapple: This looks fucking sweet. They did good with this.

So how did you guys come to do this together?

Crabapple: I’ve been a fan of Matt’s work for a long time, since back when he was writing for eXile and the New York Press. I had really liked his article on Goldman Sachs, where he calls it “The Vampire Squid.” Back in the early days of Occupy Wall Street, I felt like they didn’t have any really cool designs. So I put up a vampire-squid stencil that went viral. A friend who was working at Rolling Stone told me Matt came into the office with a bunch of shirts he had bootlegged of my design.

Taibbi: It was great! The squid had a top hat. When I was doing this book, there were a lot of images that I thought would be really striking. Molly’s work is so evocative, and I thought it would be appropriate for the labyrinthine horror of the whole thing.

Crabapple: (Pointing to the cover) The gravitas and the meat grinder. One of the things that Matt keeps coming back to in the book is that, for all we might want to think that the justice system is grand and objective, for a lot of people it’s just this rigged meat grinder that has no relation to justice at all, while for other people, who are wealthy, they can pretty much do anything and they’re fine. So I wanted to capture this evil tick-tock lady of justice who’s grinding people into pulp.

Though she’s still blind.

Crabapple: She’s a machine. She doesn’t need to see.

Taibbi: What I love about it is that it’s diabolical, but also beautiful. This gets at why I like writing about this stuff. A lot of these schemes, when you step back from them, are kind of beautiful to contemplate, because they’re so complex and difficult. You think: Who thought that up? But they’re awful.

Molly, in addition to the hellscapes that you draw on the cover and in the book, you also do portraits of people who are maybe more heroic. There’s a portrait here of Chase whistleblower Linda Almonte; for Vice recently, you did a really beautiful portrait of sex-work activist Monica Jones. Could you talk about those two styles?

Crabapple: One of the things I like to do with my art is humanize people who might have been swept away otherwise. Art is very different from photography because it’s slow. You can take a million photos with your phone, but art you have to care for. You have to put your everything into it. When I draw somebody like Monica, or Linda in here, I’m saying this person is valuable, and that this is worth looking at.

I have another picture in this book of women lining up to see their loved ones at Rikers Island. I took the bus out. They wouldn’t even let me into the visitors’ center with a pencil. I felt like this was an image no one sees, all these women dressed up really nicely to go see the guys whom they love who are locked up. They go through this incredibly sinister thing, waiting on line next to barbed wire, and then they’re searched, but they still have such dignity and gravitas, just trying to make a nice day for someone they care about.

I would try to look at scenes like that I thought were forgotten and try to bring them back from the memory hole.

Matt, you write about how a lot of the worst of these hedge-fund guys are big art collectors.

Crabapple: It’s so true. I could tell you stories, man.

Any you can tell on the record?

Crabapple: I’ve gotten offers to buy paintings from people whom I felt unclean having standing in my living room. Fortunately, I wasn’t in the position where I had to give those people those paintings. But yes, there’s this perverse thing where art becomes the modern-day indulgence-buying. You make your money as a banker destroying the economy, or as a Russian oligarch. Then you buy art to say: “Oh, I’m so cultured, I’m so noble.”

Taibbi: A lot of these Wall Street guys, they go straight from nothing, and being young and stupid and inexperienced, to having eight-hundred million dollars or even more in the blink of an eye. They pursue that relentlessly for a number of years, and then they wake up when they’re in their mid-thirties or older and realize that they’ve forgotten to live. So they’re trying to buy culture, perspective. A personality. There’s just a huge gap in these people, and they’re trying to fill it by buying art. With these instant-million guys in the hedge funds, they’re the biggest patrons. It’s not the slow, make-money-over-time guys.

A lot of artists who go through MFA programs have massive amounts of debt.

Crabapple: They do. I dropped out of school, so I don’t have that educational background, but the way you would become a big artist would be to go to Yale and take on tens and tens of thousands of dollars in debt, and then you would go to New York and work for fifteen dollars an hour making someone else’s art for them. Maybe if you have a lot of money, you get a studio and pay other people to make your art for you. The whole thing is swapping in your name and your connections and has very little to do with what I think is essentially a blue-collar trade.

Taibbi: Really?

Crabapple: Think about what I’m doing. I’m taking wood, I’m fucking prepping it with gesso. I’m doing this physically demanding hand skill where I’m making it look cool. I’ve done so many murals on construction sites, and there’s no way that I can be like: “Oh, I’m totally better than you, construction workers.” We’re doing the same fucking thing.

Taibbi: I remember when I was talking to you about animating something, and I saw you flexing your hand, because you were already thinking about how much that would hurt.

Crabapple: It’s donkey work. (Laughs) Art at its base is a combination of blue-collar labor and metaphysics, and when people get away from the blue-collar aspect by hiring other people to make their art for them, which everyone who’s big does, I feel such contempt for them. They’ve abnegated the entire heart of what they do.

Do you think that artists who have gone through MFA programs are trapped by their debt into essentially collaborating with hedge-fund guys?

Crabapple: I don’t think that they see a conflict. Also, most of them don’t get to sell out and collaborate with hedge-fund guys. I think most of them are trapped by their debt into taking teaching gigs.

Taibbi: I don’t think they should feel guilty about relieving those guys of some of their money.

Crabapple: I don’t, either. I couldn’t sell to this one guy. I couldn’t imagine something that I put so much energy into living in that guy’s house and hanging out with him every day. It felt creepy. He wanted to buy this piece [the original of The Divide cover].

Taibbi: Wow.

Did he know the story behind the piece?

Crabapple: No, he thought it was patriotic. He said: “I love Americana.”

All three of us laugh for quite a while.

I guess it is Americana, of a kind.

Taibbi: Reverse Americana.

That reminds me of a blurb on the book, Matt, that likens you to Mencken.

Taibbi: I get a lot of bad comparisons. Hunter S. Thompson is a bad comparison. Mencken is someone I actually did try to emulate. Thompson was basically writing fiction, dynamic, crazy, hallucinatory. Mencken, though I don’t agree with a lot of his politics, was a funny commentator who was recording history. I think that’s something to aspire to.

Could you talk more about how you see yourself?

Taibbi: I’m kind of with Molly. To me, it’s just work. It’s hard to think about things like where your place is. It’s not for you to even think about.

One thing that was interesting about this topic is that I went for many years writing on the fringes of the news, and then suddenly Occupy happened and I was right in the middle of everything. People were carrying squids at marches. It was really thrilling to be part of that, and to have your work be in the middle of that. And I think Molly went through the same thing. Both of us will probably be associated with that time forever, which is cool.

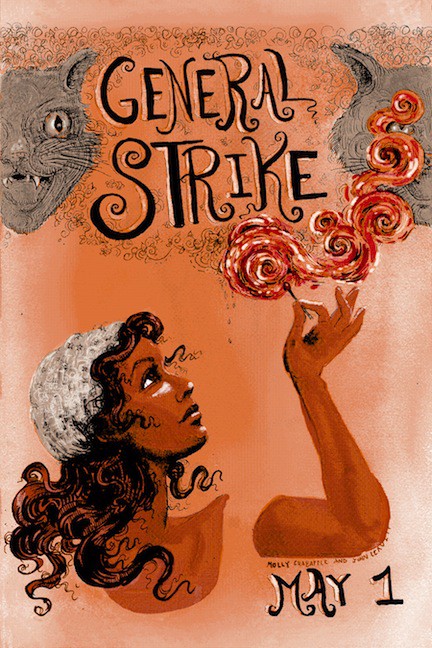

Crabapple: I’d make protest posters and I’d put them online, and people would download them and they’d be using them in marches within hours. It was the most exhilarating, alive use of my art that I could imagine. The poster that MoMA eventually bought was pasted all over the world, and that means a lot more to me than any gallery show. Not having it as a butterfly pinned to the wall, but having it be free.

Molly, I talked to Melissa Gira Grant recently about the community you guys formed at Occupy Wall Street. Could you talk about that?

My loft is across the street from Zuccotti Park. I turned my loft into a place where people could drink whiskey and charge their laptops and file their copy. So I had this group of occupiers, writers, and activists hanging out at my place all day.

And your work hadn’t been political before Occupy.

Crabapple: I’d been a political person, but I didn’t want to do it in my work. Political artwork always looked like this preachy lie. When Occupy happened, it felt like a defining moment and I wanted my art to engage with it. People were taking over streets and getting pepper-sprayed, and it was the most important, vital thing, and how could I not?

You’ve both talked about yourselves work as workers, and one of the major questions of this series I’m doing is what work means today, when the richest people don’t seem to be making anything.

Taibbi: That’s a good question. What is work in modern America? A striking thing about the group of people that I write about is their utter non-productivity. A lot of people compare them to robber barons, but the robber barons built railroads, they built this country. This whole group of people is about wealth extraction. That’s all they do. They come up with ways to take shit from people. And they’re very good at it. The things that they build are devices for separating people from their money.

I think that’s one of the reasons why there’s so much resentment towards this class of people. Their traditional job was to fund American industry and put us all to work. They were supposed to put money together with ideas and create jobs. There’s a reason to pay people a lot if they do that well. But that’s not what they do anymore.

Crabapple: I totally agree. The flipside is that working-class jobs where people used to make things are largely outsourced, and those jobs are being replaced by service jobs. What you’re selling, in addition to your labor, is your ability to project certain sorts of feelings, to smile and pretend that you like it. On both ends, you’re far away from building anything real.

Taibbi: When you make something, it’s dignified. That’s one of the problems that people have in this country. Even when people have jobs that pay them, there’s often no dignity in it. When you think about waiting tables being a good job in this environment, that’s a distressing thing.

Molly, we were talking a bit before you got here about police harassment, and I was thinking about Monica Jones and Melissa Gira Grant’s book about sex work. Do you think that ties in here?

Crabapple: Matt talks about one sex worker who is continually harassed and arrested. A lot of the laws against sex work are in reality ways of harassing trans women and women of color and poor women. That ties very much into what Matt’s writing about, about how these laws are just ways of harassing and policing the poor, ensnaring them into this system where they’re just locked in cages and taken out and locked in cages and taken out.

Taibbi: There’s a fascinating tidbit I found in there about the numbers of busting prostitutes as opposed to johns. Much more frequently, with each passing year, they arrest the sex worker and leave the customer alone. That’s absolutely part of The Divide. Both parties are guilty — I think it’s an easy argument to make that one party is more guilty — and yet that’s not where we’re throwing our resources. It would make a lot more sense, and be much more effective, to shame the man who used sex workers.

Crabapple: I’m for shaming no one. I think it’s a pattern of harassing poor people. Matt has a great part in the book where he talks about all the laws that we’ve all broken. Getting into shouting fights with our girlfriends, writing “Fuck The World!” on a fence or whatever. I’m white and middle class, so I’ll get away with that shit, whereas someone who’s poor and brown will get locked up and get a record for it.

Matt, you end on a somewhat hopeful note.

Taibbi: A little bit. That’s partly because I’m always encouraged to do that. You’re not supposed to depress people for a living. But if you look at last year, with the decision to go after Chase — even though they did a terrible job of it — they wouldn’t have done that if there wasn’t a lot of public anger. So I do believe that they’re hearing some of this stuff. But they’re not hearing it fast enough.

And the other side of the story — the exploding prison population — that’s not going to change any time soon. There are too many political imperatives lined up.

Where do you think this hatred of the poor comes from? It’s always been there, but it seems to be getting worse.

Crabapple: I think sometimes you demonize what you fear becoming, and if you’re a middle-class person, your grasp on security and stability has gotten more and more tenuous over the years. The buy-in to having a safe, comfortable life has gotten higher and higher, and you’re actually quite close to becoming poor. You’re one mistake, one illness away. To emotionally cope, you say: “These people are scum, they’re fucking lazy, I will never become like them because I’m better than they are.”

By the same token, we all think that we can become millionaires. So we think: “Don’t tax those people, because my plumbing business is just one year away from putting me in that strata.” So I think that it’s based on aspiration and fear.

Taibbi: I think that’s exactly right. I also think it’s been exacerbated by lobbying and mass media. There are interests that want to deregulate the economy, and so have to come up with justifications. There’s a sweeping public relations effort to tell ordinary people that entrepreneurship is what drives America, and that it’s lazy people who took out mortgages they couldn’t afford who are to blame for the crash. So there’s a lot effort to accelerate the blame and adulation.

Molly, could you talk about your own writing?

Crabapple: It started when I was arrested at Occupy and wanted to write about how shitty it was. Since then, I’ve been getting more and more assignments. People seem to like the combination of my art and my writing.

One of the greatest strengths and weaknesses of visual art is that it’s ambiguous. You can project whatever you want on it. “It’s Americana! It’s happy.” I sometimes like using words to be able to say exactly what I mean.

Matt, could you talk about the new magazine you’re creating for Pierre Omidyar’s First Look Media?

Taibbi: I’ll be doing a lot of the same kind of work, but I grew up reading satirical magazines, and I was really into practical jokes. I want to get back to a little bit of that. I love the turn that my career has taken, but I’d also like to do something funny. This book is very dark funny. I’d like to add a little bit of light.

David Burr Gerrard’s debut novel, Short Century, has just been published by Rare Bird Books. He can be followed on Twitter. The interview has been condensed and edited.