The Toilet Man

The toilet man was obsessed with numbers. Like the number of days he had left to live. Ten-thousand five-hundred was about how many days he said he had left, if he lived to be eighty. Thirteen years ago, the Toilet Man said, he turned forty and asked himself, how long is one lifetime? Then he checked the national statistic: eighty. So, forty more years; fourteen thousand, six-hundred days more days, give or take. “And then you die,” said the Toilet Man. He lingered over the last world, stretched it. “Dyyyyyyyeee,” it sounded like.

Back then, before he was the Toilet Man, he was Jack Sim, a rich Singaporean, running 16 businesses, having a midlife crises, searching for meaning and finding none. “What’s the purpose of having more money?” he thought. “I mean it’s crazy! When you have no money, you need to sell your time for money, and when you have money, you sell your time for money. It’s a losing business.” And it was confusing. “Time is the only currency of life” is what he concluded, and so endeavored to do something different with his.

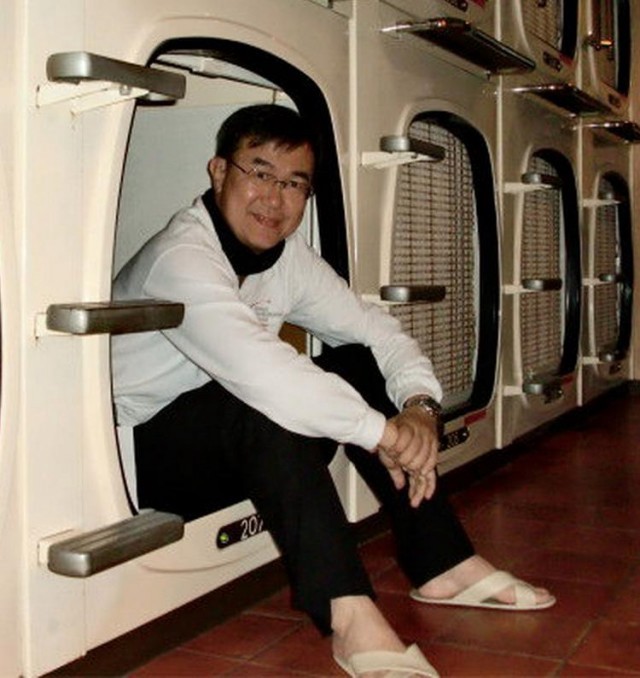

It wasn’t toilets. Not at first. First he tried volunteering with the SOS, which was a listening service for distress phonecalls. A suicide hotline, more or less. He trained for nine months before he took his first call and then, not long after, realized it was a miserably lonely job. People didn’t call. And then when people did, he couldn’t help them all at once. So he tried something else. He helped conserve old buildings, which meant spending a lot of money on renovation and he thought, “Hey, this is a very expensive hobby!” so he dropped that, too. Soon after, still searching, Jack Sim read something Singapore’s prime minister at the time, Goh Chok Tong, had said. It involved toilets. “We should measure our graciousness against the cleanliness of our public toilets,” is what Goh Chok Tong said. And Jack Sim thought to himself, “Hey, that’s the one! Nobody’s going to handle this one. That’s going to be my job!” and he started the Restroom Association of Singapore to clean up the public toilets. People loved it. He then realized there were 15 toilet associations around the world, in cities in Britain and Germany and Japan and some other places, too, but no world headquarters. So he started the World Toilet Organization, a kind of play on the World Trade Organization, and that is how Jack Sim became the Toilet Man. People call him Mr. Toilet, too.

The Toilet Man just got back home from India. He spends a lot of time there now, because India needs a lot of toilets. He is good at raising money for toilets, and motivating people to clean toilets, but his biggest thing, the thing the Toilet Man likes doing most of all, is to get people talking about shit. “I’m a bit of a naughty boy,” the Toilet Man said, and then explained that this was because he was the youngest child in the family. Toilets, said the Toilet Man, need a common language, we need to talk about our shit as much as we talk about food, and anyway what happens to food afterward? It ends up in the toilet! The next step is to make the toilet very sexy, create a fashion trend, where Bollywood stars talk about toilets. In Germany they are very good at talking about their shit. In India, it’s a taboo.

Just then someone, a tall skinny man, approached quietly and softly said, “Jack, so you have a fan. She is very shy. She’s standing over there,” and he pointed to a woman across the wide hall, over by a table, who looked away when we all turned toward her. “She wants to get a signature,” the quiet man said, and then passed the Toilet Man a magazine and a pen.

“What is this?” the Toilet Man said.

“It’s a magazine. You’re in it,” the quiet man said.

“Oh! OK! Soooooo…” the Toilet Man flipped through the magazine until he found a page with his picture on it, and underneath, the headline “Man of Missions.” He laughed and signed the magazine and handed it back to the quiet man, who took it over to the shy woman across the wide hall.

“Did you see, they didn’t print the world ‘shit’?” the Toilet Man said. “It’s ugly, people don’t like to talk about it. It’s scary. When I grew up, we had the British bucket system, which was terrifying, all the colors and smells of other people’s shit. That is some of my first memories. And it’s scary. When we moved from a hut into a flat, the first flush made us feel wealthy. Today, what we are doing now, we conduct a survey of people going to the toilet before and after, and you will find that most people, ninety-nine percent of the people, are happier after. Maybe one percent had a bad time. So the toilet is actually a room, a happiness room, for almost everyone. It’s a joy! It’s a luxury! Let’s celebrate the toilet. Let’s talk about it like that. Oh the subject is so embarrassing otherwise, the only way to break the ice is to make fun.”

“And the customer! No one thinks of the people, if they are poor, as customers. In Germany, Japan, they are good at talking about shit, and they have very good toilets, very advanced toilets in Japan. But we can’t take that to India. You have to customize, obviously, and think about the terrain, yes, the hydrology, yes, the affordability of the people, yes. But most important, the thing we forget, is what is sociologically acceptable. It’s the customer. Are they wipers or washers, squatters or sitters? You have to be very, very sensitive to the customers. If they don’t like the toilet, they will turn it into a store room, rich or poor. You have to make them want the toilet,” said the Toilet Man, standing up. “I have to go, now,” he said. “I have to go give a talk about toilets, of course.”

Ryan Bradley is a writer and editor in New York.