It's Time To Unionize In Silicon Valley

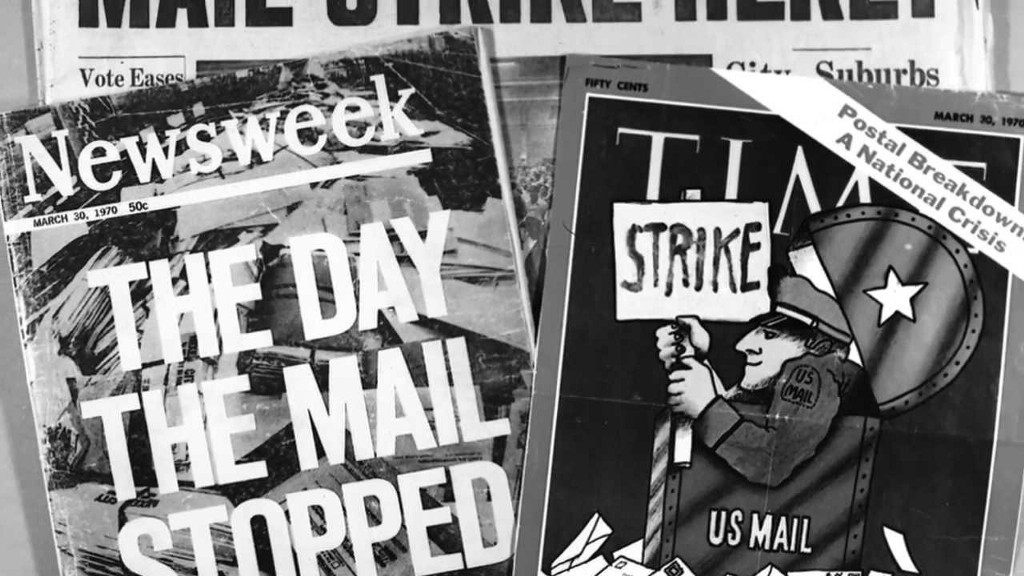

What can programmers learn from the U.S. Postal Service strike of 1970?

In March of 1970, William Burrus watched the National Guard surge into the post office where he worked in Cleveland, Ohio. Burrus, a black man from Wheeling, West Virginia, stood with his coworkers at the entrance of the building as the reserves, clad in fatigues, rifles in hand, arrived in Jeeps and tried to quell a national strike. Postal workers were incensed by a recent vote in Congress that provided them a 4.1 percent raise while giving the representatives a 41 percent spike in pay.

Months earlier, on July 1, 1969, nearly all the letter carriers and postal clerks from the Kingsbridge station in the Bronx had called in sick for the day. When the postmaster suspended the workers, letter carriers from the nearby Throgs Neck station did the same. The members of the National Association of Letter Carriers branch #36 in Manhattan, separate from the Bronx postal workers yet well aware of their actions, had also been tired of low, stagnant wages. On March 18, 1970, they voted 1,555 to 1,055 in favor of a strike. The demonstration started in New York City, but it spread quickly to more than 30 American cities, from New England to San Francisco, as reported by Time Magazine. More than 200,000 postal workers participated, stopping or at least curtailing the delivery of mail far and wide. Many postal workers from the southern states who had never been politically active also took part, Burrus recently told me.

The strike disrupted business on Wall Street, leading New York Stock Exchange officials to consider a market shutdown. An elderly woman living in Manhattan’s Beacon Hotel told Time, “I live on my stock dividend checks and I’m expecting some right now. If this goes on for much longer, I’ll just have to start dipping into my savings.” The poet W.H. Auden worried he would not receive his passport in time for an April trip to Israel. The strike reportedly did not affect the hundreds of thousands of welfare recipients in New York City. Most of these checks were delivered before the stoppage began.

President Richard Nixon, flustered, promptly ordered the National Guard to storm post offices throughout the country and resume the delivery of mail. Burrus, who would later become the first black American to be elected president of a national union, knew that was pointless. You can’t walk into a post office and organize mail like you might organize your basement. It takes training.

“We asked them whether they were going to shoot the mail or sort it,” Burrus said.

The strike lasted more than a week and ended only when the rank and file secured an additional wage increase of six percent. That figure would rise another eight percent following the passage of the Postal Reorganization Act, which Nixon signed into law on August 12, 1970. The legislation established collective bargaining in the industry and allowed employees to reach the top of their pay grade in eight years, instead of the former 21.

Last month, as you might have heard but hopefully did not, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote a letter to his congregation. In this letter he wrote about “spreading prosperity and freedom, promoting peace and understanding, lifting people out of poverty, and accelerating science,” and his congregation said “amen” and “holy holy” and, prostrated, “Thank you for your leadership and vision, and for putting forward a positive vision that we can all be a part of. This is how we all start to understand each other a little better and make the world we want.” And so it was.

Such idyllic talk counts as standard fare for Zuckerberg and his rival world-engulfing executives. Zuck’s perceived credibility is based on his innovation, which has helped globalize communication — an accomplishment only made possible by a fleet of loyal programmers. Programmers tend to be ethical and trusting, said Valerie Aurora, a former Linux programmer and principal consultant at Frame Shift Consulting. The average programmer is well compensated to work in a nice-to-luxurious office for a company that promises a vision anchored by Gandhisms. The philosophies are strengthened when, for example, Google co-founder Sergey Brin shows up at the San Francisco airport to protest Donald Trump’s immigration ban. Yet despite the gospel of perfection shared by Zuckerberg and other tech giants, they consistently repress the rights of their employees and act in the best interests of corporate expansion, not civic justice.

In the months after the election of Donald Trump, members of the press have contributed several necessary polemics against Facebook’s manipulation of personal data, its propagation of confirmation bias and its overwhelming influence on political thinking, to name a few. Google has relinquished some of its market share, but nonetheless carries on largely unquestioned. It would be fair, by the way, to doubt the potential efficacy of a lawsuit filed recently by the U.S. Department of Labor over requests for compensation data. The clandestine power of these corporations perpetuates their dominance and routinely weakens intervention from government and various forms of activism. The silence around Google and its competitors is by design.

It’s no secret in Silicon Valley that programmers work well beyond the 40-hour week accounted for in their salaries. Aurora said that every one of her friends at Google works nights and weekends. During her time as a developer of Linux kernel, an operating system used in technology sold by Intel and IBM, among others, supervisors constantly assured her and fellow programmers that they love their work and that they love it so much they will do it for free. To ensure persistence and efficiency, supervisors use a complex recipe of emotional abuse and, if you play along, eternal job security.

Many programmers, including those at Google, are told that they are prohibited from talking to the press about their work. They are lectured repeatedly about this rule and ordered to sign non-disclosure forms. Lawyers must review any papers for conferences. Supervisors hold these mandates against their employees, who typically don’t question such restrictions or speak up about harassment so they may keep their jobs. Lower-level employees, who also strive to be a part of something bigger than themselves, desire what anyone else wants in a job: the ability to feed their families, pay the mortgage and have something left over. But as the years pass and the companies grow, this working structure gains momentum at the expense of the rights of workers. Aurora referred to it as “a culture of fear.”

“If you want to have a career in computers,” she said, “it does not pay to talk.”

There should be no muddling of the postal industry, which is dwindling, and the tech industry, which has in many ways taken its place. But discontent is universal. In the 1930s and 40s, when William Burrus grew up in Wheeling, West Virginia, a small town along the Ohio River sandwiched between the more tolerant states of Ohio and Pennsylvania, he attended “a colored school.” In the first four years of his education, he went to five different schools, shuttling between states so he might avoid the brutality of segregation. His sister walked across the river every day to Bridgeport, Ohio, where she went to the same high school attended by basketball legend John Havlicek.

When Burrus graduated high school, there were five nearby colleges that, by law, he couldn’t attend. Brown v. Board of Education was decided two weeks after his graduation, but the uncertainty of its effects led him to the army, followed by a long career as a postal worker. It was not until October 2001 that was he elected president of the American Postal Workers Union. He knows that the AFL-CIO headquarters in Washington was built with the intention that a black person would never work there. He ponders the American invention that states: “all men are created equal.”

“Slavery didn’t mean that,” Burrus said.

In the past few years, Americans have fiercely protested the injustices of powerful institutions. Black Lives Matter catalyzed movements in Ferguson, Missouri and Baltimore, among other cities, that stand for the refusal to accept the killings of young black men. Recent marches countered Trump’s inauguration and celebrated women’s rights to promote gender equality and reproductive health choices. In January, thousands of people stormed airports and streets throughout the country to protest President Trump’s immigration ban. Even Occupy Wall Street, for all its dysfunction, can be viewed as a preamble to the rise of ideas about economic inequality that so many share with senator Bernie Sanders.

Tech workers, despite the massive powers that employ them, have begun to gradually implement traditional forms of dissent. Susan J. Fowler, a former Uber engineer, last month wrote a blog post that outlined a host of internal problems, including gender inequality, sexual harassment and general apathy about these issues from executives and the human resources department. In response, Travis Kalanick, the company’s indignant chief executive, has since launched an internal investigation, to be led by Arianna Huffington, a board member, and former attorney general Eric Holder.

Valerie Aurora could also no longer tolerate emotional abuse, sexual harassment and heavy restrictions, so she left Linux and has since pushed incessantly for labor rights. In 2011, she founded the Ada Initiative, an organization that promoted the rights of women in the tech industry. She champions the activism of Liz Fong-Jones, a Google engineer, transgender woman and daughter of immigrant parents, who advocates for change from the inside. Fong-Jones has worked alongside her colleagues to identify the greatest internal problems at Google, mobilize powerful engineers, devise a request and find those who can grant that request. Keeping with company policy, she has been sure to refrain from talking to the press until internal dialogue is through. After the 2016 election, Buzzfeed News reported that a few dozen Facebook employees launched an unofficial task force to combat the proliferation of inaccurate news.

Aurora and her fellow activists are calling for more innovation in dissent. Otherwise, she said, powerful institutions will too easily dismantle the efforts. “Part of the tension that you get for it is the novelty.” She cited the troubles of Turkish activists, who have tried pioneering mobilization techniques so they may rise above the injustices of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has repressed free speech by forcing journalists out of their jobs and prosecuting online dissidents. There are few examples in the tech field of employees standing for justice over the interests of corporations and government, and their present dissociation weakens their magnitude.

Indeed, a protest can be remarkably effective and still not reach its full potential. Burrus attributes the pattern of activist dissociation to what he called “the imperfection of human beings.” We typically prioritize our rights and the rights of those closest to us over the most pressing civil injustices of a larger scale. “Billions of individuals will rise at their truth,” he said.

The majority of the people in the tech industry would greatly benefit from labor organization not unlike the postal workers before them. However, the frequently corrupt relationship between tech workers and their supervisors, often veiled by the term “meritocracy,” has thus far successfully muted dissent. This silence must come to an end, regardless of corporate motives, and it will occur only when workers throughout the industry stand together for justice over personal, immediate gain. Imagine the havoc if programmers stopped programming, apps stopped updating, and we entered software sclerosis. “Employees who are committed to fairness of employment, even when the government is the employer, can achieve their objectives if they stick together,” Burrus said. “And that’s what happened in 1970. We stuck together.”

Max Rothman is a writer and social worker in New Orleans.