London's Last Class War Street Party! Farewell Witch Thatcher, Say Aging Punks

by TG Gibbon

In the early 90s, the great anarchist newspaper Class War suggested that on the first Saturday after the death of Margaret Thatcher, the people should gather at 6 p.m. in Trafalgar Square to celebrate. As anyone even vaguely familiar with lefty infighting knows, the memory of the anarchist is long and thorough, so after Thatcher died on Monday, some of the old guard and fellow travellers dutifully showed up. The original incarnation of Class War is now defunct so there wasn’t anybody in particular managing the thing. This protest was neither spontaneous nor especially well-planned, so it didn’t benefit from clear organization, nor did it evince the awesome, unwieldy, atavistic force of a purely spontaneous outpouring.

It was a nice crowd of Old Warriors (some now New Age and bourgeois, some still with their squatter’s teeth), some hippie students, some hipsters, some neo-folk looking folks, some Irishmen well up for anything that might go down, a couple of actual covered-face anarchists, bags of Northerners, plenty cops and plenty journos. Basically it looked like a big crowd of bicycle messengers. Naturally everybody had cameras. When we first arrived, one of several David Threlfall impersonators asked us “Are you looking to have a good weekend?” We politely demurred, assuming he was trying to sell us something; we were Americans in central London after all. But after a few minutes he finally made himself clear: he was hoping we would rally the troops by posting to Twitter and Facebook with the hashtag #GetOutHere. Okey dokey. Still, I would like to take this opportunity to apologize to the man; nothing is worse than suspecting someone of trying to sell something.

There was a hippie-chick with a baby strapped across her chest like body armor and a lady cop with body armor strapped across her chest like a hippie sprog, but there was a noticeable preponderance of males. There was also a massive preponderance of Special Brew, the notoriously strong lager (9% abv) associated with soccer and other hooliganisms, although occasional wafts of cannabis did occur.

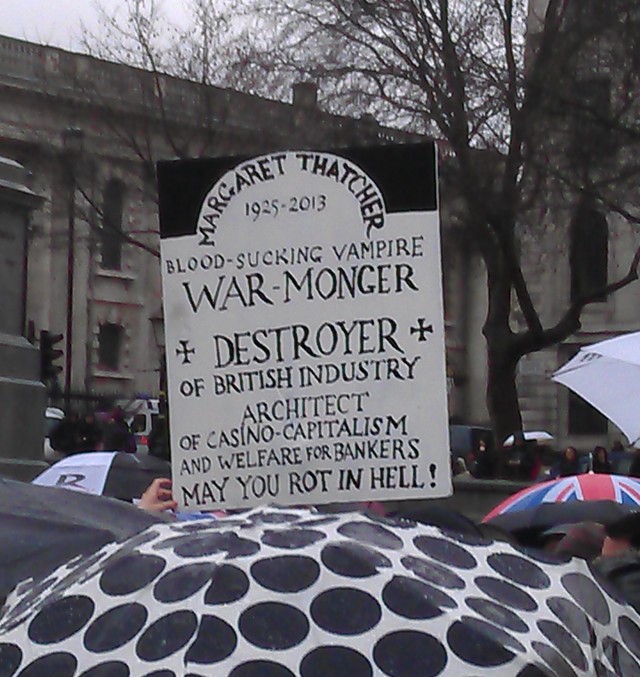

But there wasn’t really much going on: no speeches, no bands, not even a central stage or podium. Instead it was like an anarcho-Quaker meeting where anyone with something to say could say it but only the very loud would be heard. A man dressed as a sort of Regency vampire and holding one of the few placards on display made a nice speech to those who could hear. A few old fellas from the National Union of Mineworkers arrived to a big round of cheers and applause as they unfurled their union banner and marched it through the crowd. This sort of banner is a mixture of Victorian chintz and Soviet socialist realism but somehow altogether moving. There was also a giant fucking puppet because welcome to Europe. It was an appropriately ghoulish Thatcher and had orange, plastic grocery store bags for the hair, which was kind of nice and seemed fitting.

The main activity often seemed to be mugging for cameras. One of the Irish contingent would run at top speed across and through the crowd every time he spotted another temporary locus of attention. One man on the stairs delayed opening up a celebratory bottle of champagne until he’d been positioned better for the cameras. TV crews and cameras were in abundance in spite of the inaction. So when something did come up they raced heedless, much like a half-drunk Irishman, through the crowd, knocking and bashing along their way. But even with this behavior they were on the whole the main stars of the show. It was the attention of the cameras that was necessary, not for self-aggrandizement (although as in any group of two or more people, there was plenty of that) but for the very success of the event. Without decent news coverage it was just moistened Britons.

A late-middle-aged veteran of the 80s ran through the crowd exhorting people to be livelier, to smile more: “We’re here to celebrate, not to mourn!” But everyone’s mood, it seemed, was depressed by the weather and the turnout. Now some might think it uncouth to publicly celebrate the death of a demented pensioner but if there’s one thing I learned from Roger Ebert it was to judge things on their own terms — the terms they bring to the table. Thatcher made it quite clear what she thought of respect for the dead and her corpse deserves no more respect than she had for the 332 Argentinian boys killed outside the exclusion zone in 1982 on the ARA General Belgrano (formerly the USS Phoenix). When asked how people should react to that news, she said, “Rejoice!” No, she was no mere demented pensioner, no simple gran, no mere stranger on the street. She lived by different rules and she died by different rules.

There were occasional chants and attempts at song. “Ding-Dong, the witch is dead!” from The Wizard of Oz — which was propelled into the Top 40 charts as an unofficial anthem of anti-Thatcherism and was subsequently not played in its entirety on the BBC Radio 1 chart show for political reasons, much like the Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” almost 40 years ago — would sometimes start up but die out pretty quickly, because nobody seemed to know more than two lines or actually like the song. The Liverpudlian cadre put up the chant/song “Justice for the Ninety-Six” in reference to Thatcher’s shameful response to the 1989 Hillsborough disaster, which killed 96 Liverpool FC fans (more evidence of her respect for the dead), but nothing could really ignite the crowd.

I felt awkward taking part in the chanting. Not because the main one was the possibly morbid “Maggie! Maggie! Maggie! Dead! Dead! Dead!” but because, well, chanting. I had decided after my first big demonstration, the 1992 pro-choice march on Washington — which my high school had bussed some of us down for — that I didn’t much like crowds. Especially crowds gathered together for a single purpose and of a single mind. The “moral man, immoral society” dilemma. I held out well until 2003 when I twice marched against the Iraq War. Fruitless that was but I still think it was important to be counted — and to be counted swathed head-to-toe in Brooks Brothers so it could be seen that it wasn’t just weirdos who opposed pointless and illegal war. Generally I still avoid crowds. I don’t even like it when people at concerts cheer or people at comedy shows laugh. Live-action, mass activity always channels a little Nuremberg for me.

So I showed up a bit cynical but willing to be converted. I was in Scotland in May, 1997, when the Tories were finally driven from power. There weren’t any demos (why would there be? “We” had won) but the feeling on the street the next day was electric. Scotsmen smiled and waved at strangers. Everyone walked with the springy step of the acquitted. They thought they’d finally gotten their country back. This was a chance to maybe feel that joy, that human unity, again.

Someone later that night asked me why I thought it was so important to go. I didn’t say anything about the workers’ struggle being universal. Nothing about borders being fences put up by the rich to keep their cattle in (a subtle but hopefully cutting dig at our friends in Plaid Cymru and the SNP). Nothing about Thatcher acting as midwife to the current decrepit world order. No, none of the things I’d practiced to myself at the demo to say if any old soldier of the time, offended by my clothes, challenged me. I said I went because I wanted it to be big. That if I was able to break through my laziness and the rain, hopefully that meant, statistically, that other people would as well. And the importance of it being as big as possible was to get the most press as possible. So that it would be an undeniable challenge to the prevailing media narrative (as we say) that “whatever you think of her policies you have to respect her [something-bland].” Because, well, no, I don’t. Content is important, still. No one says “You may disagree with Ed Gein’s killing-and-skinning women policy, but you have to respect his pluck and determination” because killing and skinning women is a terrible thing to do. Yes, I am comparing her to a notorious serial killer and I know it is an unfair comparison; Gein may have treated individuals far worse but he did far less damage to his country and the world. This blind even-handedness that culminates in the BBC censoring a 70-year-old song had to be faced down.

But it wasn’t. We didn’t have the numbers. It was a depressing and at times desperate affair. I thought back to the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902 in Pennsylvania. Here we were over a century on and it looks like the operators had won the long game.

The real victory lap of capital in the class war won’t be Thatcher’s semi-state funeral (partially funded by taxes) on Wednesday; it was this anti-Thatcher demo on Saturday night in Trafalgar Square. We had gone to celebrate her death but we ended up mourning the Britain — the Britain of Hope and Glory — that she had so wilfully murdered. According to the Guardian, about 3000 bodies turned up. Capital needed it small and we bloody well gave them small.

We left after about an hour-and-a-half into the rain and slinking dark and the throngs pouring out from bars for a smoke on a wet Saturday out. So maybe I left a little bit more cynical but still with at least a toenail willing to hope. We may not have been enough but we were there. All these people who did not know each other had come together for the benefit of even more people they did not know. As rally turned to pub and evening turned to night, society still existed and Margaret Thatcher did not.

TG Gibbon is on Twitter but doesn’t have a phone that can do that sort of thing. Photos by Jeremy K. White.