Brooklyn Academy of Music

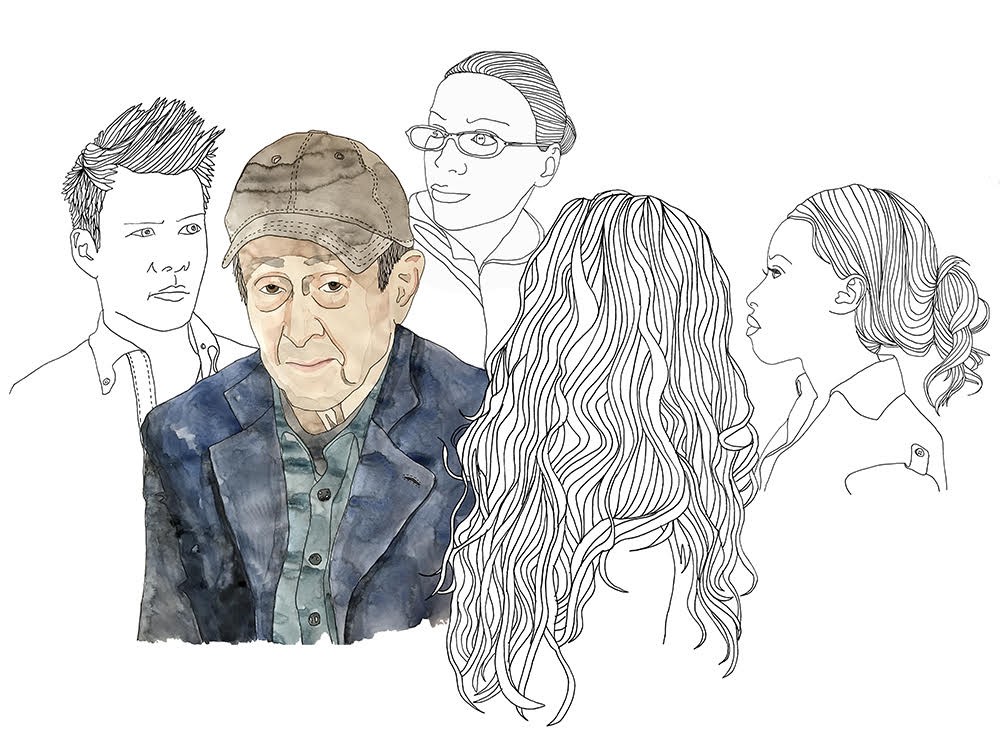

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

OK, you were not quite a stranger, in that you were a known person. To me, more-than-known — an idol, almost, which seems a preposterous word to use about a person who is neither Rihanna nor Beyonce nor the Virgin Mary, but a late-middle-aged white guy called Steve. A guy called Steve in a baseball cap. I speculated on this trademark headgear as if it were a relic-in-the-making. “How many hats do you think he has?” I whispered to my husband, carried away by my own inanity. Easier to be inane than awestruck. “Or is it just the same one, always, and it smells really bad but no one says anything?”

My God, I would have been so mortified if you’d overheard this. As with Beyoncé, your name is a sort of impossibility — something separate, in my mind, from a human being who yawns or makes coffee or files taxes or is bewildered to overhear his wholly unostentatious hat discussed by strangers. Instead, your name registers as the designation of a kind of god. I know this: that the work is the godly thing, not you, but still, it has your name on it.

You wrote a piece of music I listen to as regularly as I shower. Like showering, hearing it is a kind of hygiene. I sit up, plug in headphones at my laptop, and the sound is Pavlovian; I feel like a pianist, fingers raised with readiness above the keys. I am instantly alert, vivified, braced into sentence-making, brisk-thoughted mode. Most miraculously, its magic doesn’t seem to wear out. Maybe because it’s not really ‘music’—that’s too diaphanous a term for a thing that’s more an exercise, a communal, moving construction — architectural and yet effulgent. I privately declared a relationship doomed when I saw this piece of music at the Park Avenue Armory and my companion idly checked his phone as soon as the applause began. He might as well have taken a dump in the Sistine Chapel. A pair of techno DJ friends wed to this piece of music, notes sounding radiant and staccato from a Marshall amp on the DUMBO waterfront as we witnessed from hot stone steps and one of us cried.

No way I could say any of this to you. Instead, I did something quite creepy. This is what I hope you didn’t notice: me, shifting a fraction to my right as you passed me in a crowded room just so that, yes, I could say I brushed shoulders with you.

Forgive me. There’s such satisfaction to enacting an idiom. Years back, when my husband-then-boyfriend were looking to move in together, we went hand in hand like poor fools to a broker, a sardonic Polish lady in her sixties. We announced our budget to her whereupon she actually laughed in our face. Rather than dismay or indignation I felt delight at a turn of phrase made literal. It was like watching someone slip on a banana skin, or run off a cliff and pedal, manic and suspended, before the plummet. (Once she’d laughed, lo if she didn’t find us the cheapest damn rent-controlled railroad in north Brooklyn.) In French, to stand someone up is to ‘poser un lapin’, or, to place a rabbit. I have always loved this phrase, have loved, in particular, the image of some moustachioed cad scuttling to a Montmarte street corner with a bunny in his arms and depositing it there before scarpering at his date’s approach. To brush shoulders with you felt just as silly, but also as joyful.

So here I am, having just consciously literalized a phrase, and I glance behind me, to my husband, to whom I am pledged partly because I believe he would never check his phone during a performance of Music for 18 Musicians. I look to him all flushed with my triumph, to check and see if he just witnessed this event, but he’s not looking at me. He is instead, doing the exact same thing: I see his eyes lowered with concentration as he shifts slightly to the right, a minuscule movement, but sufficient to ensure his right shoulder makes contact with your right shoulder as the two of you pass. And the moment it’s happened he looks up, meets my eye with a grin, and that grin says, “look who I just brushed shoulders with!”