This Is An Ad By Dr. Seuss, It Will Cost More Than A Caboose (If You Say His Name Wrong)

After receiving twenty-seven rejection letters, Theodor Seuss Geisel published his first children’s book in 1937. But And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street wasn’t going to pay the bills during the Great Depression.

Still, Geisel’s wife, Helen, encouraged the thirty-three-year-old, who’d left Oxford without taking a degree, to pursue an artistic career — which he did, just as practically as he could. Geisel spent his days at the New York City-based humor magazine Judge, and worked on his children’s books during off hours.

But really he was, by then, an ad man. In 1928, the wife of a Standard Oil executive was thumbing through Judge at the hair salon when she spotted Flit bug spray, one of the company’s products, in a cartoon. She encouraged her husband to hire the illustrator, and just like that, Geisel was in business. He drew the first of many Flit ads that very year, followed by a steady stream of commissions from big companies like General Electric, NBC and Ford.

The Geisels embraced their newfound comfort, shunning regular hours and traditional offices in favor of extensive European travel, but World War II brought them home with purpose. Geisel became a political cartoonist at the leftist publication PM, vilifying Hitler and Mussolini, noninterventionists and the Japanese — and also lambasting racism directed against Jews and African-Americans at home. His cartoons favorably depicted President Roosevelt’s war efforts, and criticized Congress, especially the Republican Party.

The government took notice, and solicited Geisel’s illustrations for the Treasury Department’s propaganda posters. Geisel took to the work in earnest, even seeking out a more formal role. In 1943, he became the commander of the Animation Department in the First Motion Picture Unit of the United States Army. He wrote a variety of training and propaganda films, including Our Job in Japan, part of the post-war effort to get American troops to see the occupation of Japan as the real end of the war.

After the war, the Geisels moved to La Jolla, a moneyed shoreline community known as the “jewel of San Diego.” The seven miles of jagged California coastline attracted some of the country’s most affluent families, who built upscale homes against the steep slope of Mt. Soledad, perched above sandy beaches crowded with wild seals. The microclimate ensured clement weather year-round, with temperatures rarely dropping to fifty degrees in even the coolest winter months. An offshore breeze could be felt along the cliffs, from the posh, municipal Torrey Pines Golf Course to the narrow, winding roads that ran through town.

The Geisels enjoyed their life in La Jolla, and became increasingly involved with local charities and politics. They socialized with neighbors like novelist Raymond Chandler. Much to Helen’s horror, Chandler drunkenly insisted their town was “inhabited by arthritic billionaires and barren old women!” The childless Geisels were no billionaires, but they did share most La Jolla residents’ desire to curb development in their idyllic, beachside town.

In 1956, Geisel wrote “Signs of Civilization,” a pamphlet opposing billboards for the La Jolla Town Council. It starred everyman Guss, who advertises his product, Gussma-Tuss, outside his cave, only to be bested by Zaxx, who dwarfs Guss’ sign with his own for Zaxx-ma-Taxx. As Geisel wrote, things quickly escalated:

And, thus between them, with impunity

They loused up the entire community.

Sign after sign, after sign, until

Their property values slumped to nil….

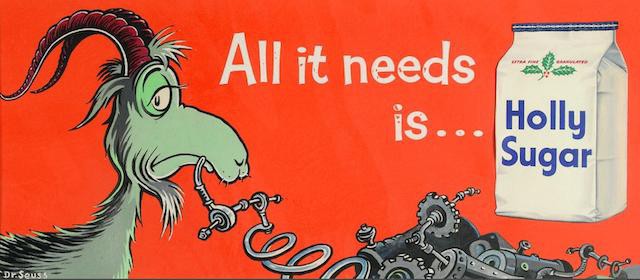

Geisel’s lobbying came as a surprise to companies like Holly Sugar, who had paid him to illustrate such billboards. Geisel spent most his post-war years focusing, with increasing success, on children’s books. If I Ran the Zoo (1950) was a runner-up for the Caldecott Medal, and Horton Hears a Who! (1955) and If I Ran the Circus (1956) found great popularity among young readers and their parents. That same year, Geisel’s alma mater, Dartmouth College, awarded him an honorary doctorate, giving him the title he had been using for years. His livelihood was no longer dependent on advertisements, and he didn’t want to them in his town any more than he wanted them on his drafting table.

Holly Sugar, situated about ninety miles north in Huntington Beach, took particular issue with their ad man’s newfound stance. Their plant, built in 1911, was dependent on the fertile geography of Orange County, ideal for growing sugar beets. They, too, were facing similar arguments from their own beachside, neighborhood communities, and quickly distanced themselves from Geisel, replacing him with Los Angeles-based illustrator Bill Tara.

It was no big loss to Geisel, who was just a year away from publishing The Cat in The Hat, which would become one of the best-selling children’s books of all time.

Tomorrow — Thursday, January 23 — Swann will auction off an advertisement Geisel drew for Holly Sugar sometime in the 1950s. They estimate the mounted gouache and collage drawing, featuring a skeptical-looking goat against a orange backdrop, to be worth $30,000 to $40,000. This drawing, at about half the size, sold for $21,600 a year ago; this small drawing sold for $33,460, three times the estimate, back in 2002.

The Geisel Library at the University of California, San Diego, is located in La Jolla, and its Mandeville Special Collections houses 8,500 Geisel items dating from 1919 to 1991, including many of Geisel’s advertisements, such as others for Holly Sugar.

Alexis Coe is a columnist at The Awl, The Toast, and SF Weekly. Her work has appeared in the Paris Review Daily, the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, and other publications. Her first book, on an 1892 murder in Memphis, will be published next year.