The Most Homoerotic Little Archive in Texas

Just how gay is The University of Texas’s Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sport?

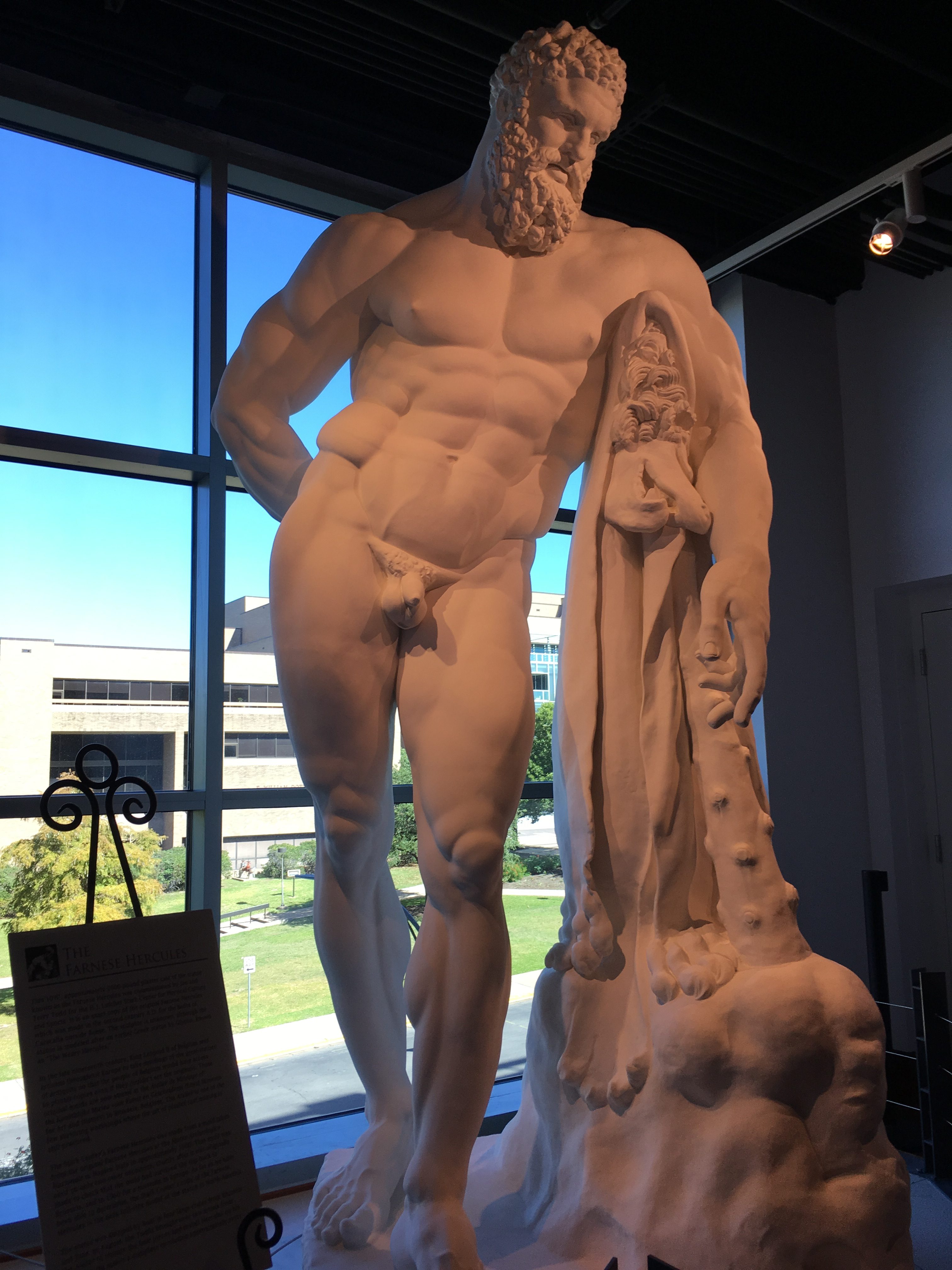

The Stark Center’s copy of the Farnese Hercules, not implying anything at all. All photos by Susan Schorn.

UT-Austin’s Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, the 9th-largest stadium in the world, seats over 100,000 fans. The massive structure, which also houses the university’s athletics offices, a state-of-the-art sports medicine facility, and an extensive strength-training complex, embodies UT’s commitment to football, and to spectacle. But tucked away in a corner of the stadium’s North End Zone is an overlooked little gem: The H. J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sport. It’s an academic archive and museum dedicated to weightlifting and bodybuilding. And it oozes, not at all coincidentally, with latent homoeroticism.

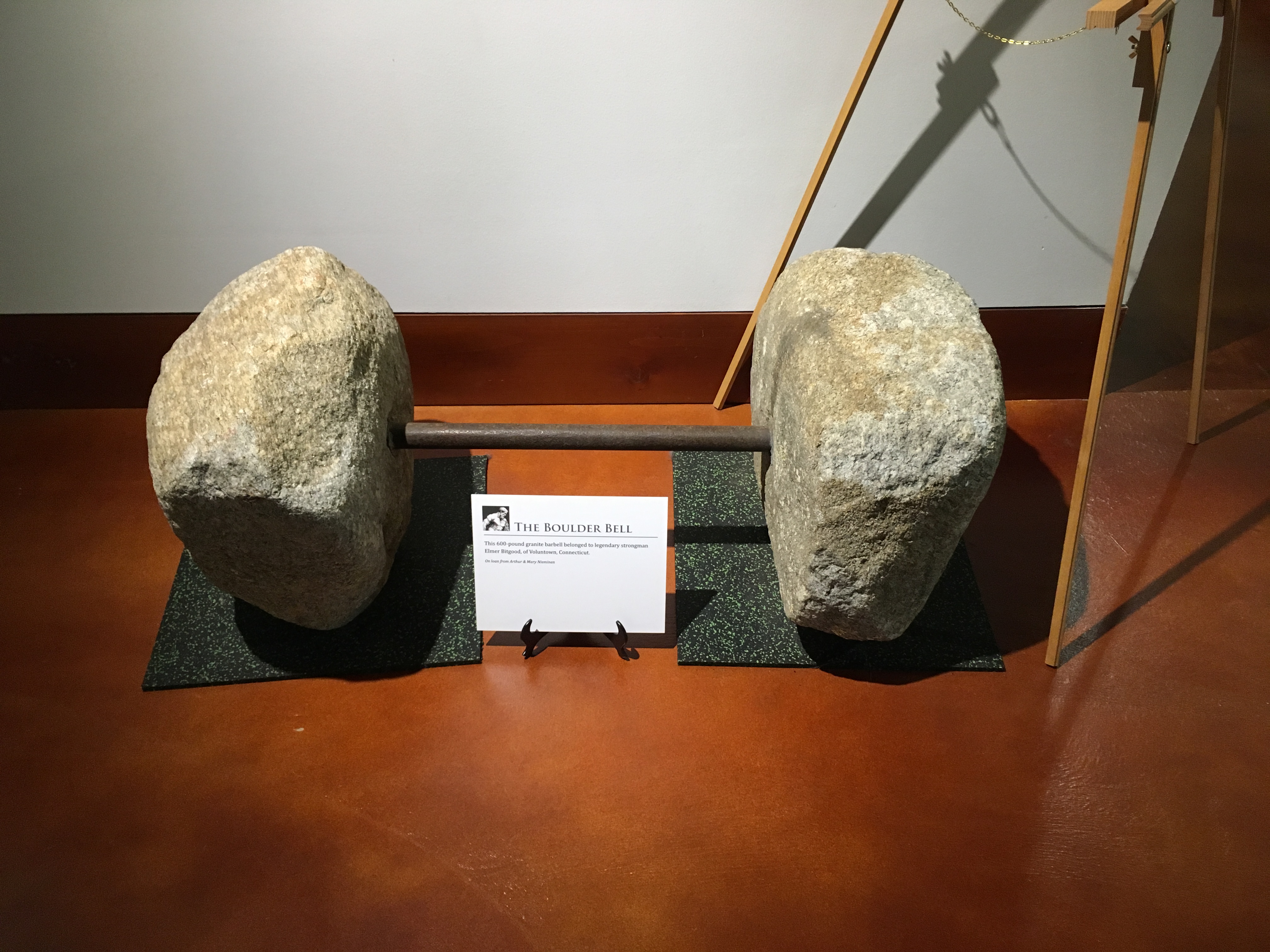

The Boulder Bell, a 600-pound granite barbell once belonging to Elmer Bitgood (on loan from Arthur & Mary Nieminen).

Or perhaps latent’ is the wrong word; the first treasure that awaits visitors entering the Stark Center is a 10-and-a-half-foot-tall, floodlit, rotating nude Hercules. This copy of the Farnese Hercules depicts the demigod reclining languidly against what appears to be a giant stalk of asparagus, but is actually his mythical club, covered by the skin of the Nemean lion. His right hand, held coyly behind his back, cradles two Apples of the Hesperides. The gallery card accompanying this astonishing beefcake whirligig helpfully explains that it is a 2,000-pound plaster cast, made in Naples from a hundred-year-old mold of the original, that it was shipped to Texas by boat in four large crates, and that Hercules “makes a complete revolution approximately every three minutes.” The card is mute on the potential significance of the large, knobby, skin-covered club, the apples, and the fact that the original Farnese Hercules was displayed in a Roman bathhouse.

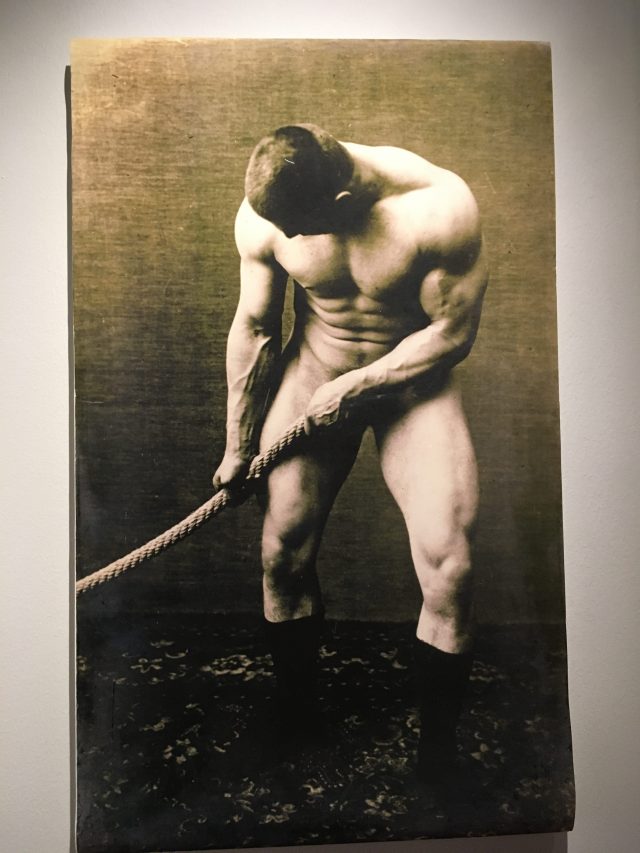

This photo of a man clad only in socks, pulling on a rope, is displayed with no context whatsoever, and I really don’t think it needs any.

A one-ton, unacknowledged phallic symbol makes a perfect introduction to the existential conflict at the heart of the Stark Center, where full-throated celebration of the body meets helpless inarticulateness about sexuality. And it feels like no accident that this tension hums within a gargantuan college football stadium. Consider that 73,660 athletes played NCAA football last season, yet this year we are celebrating a “record-breaking six openly gay college football players.” Six, by golly! Fewer than one one-hundredth of one percent of college football players, it seems, are openly gay. Compare that to the 7.3% of millennials who identified as LGBT in a 2016 poll by the Gallup organization, and it’s clear that college football has its own conflict between love of the game and another kind of love, one that dare not speak its name.

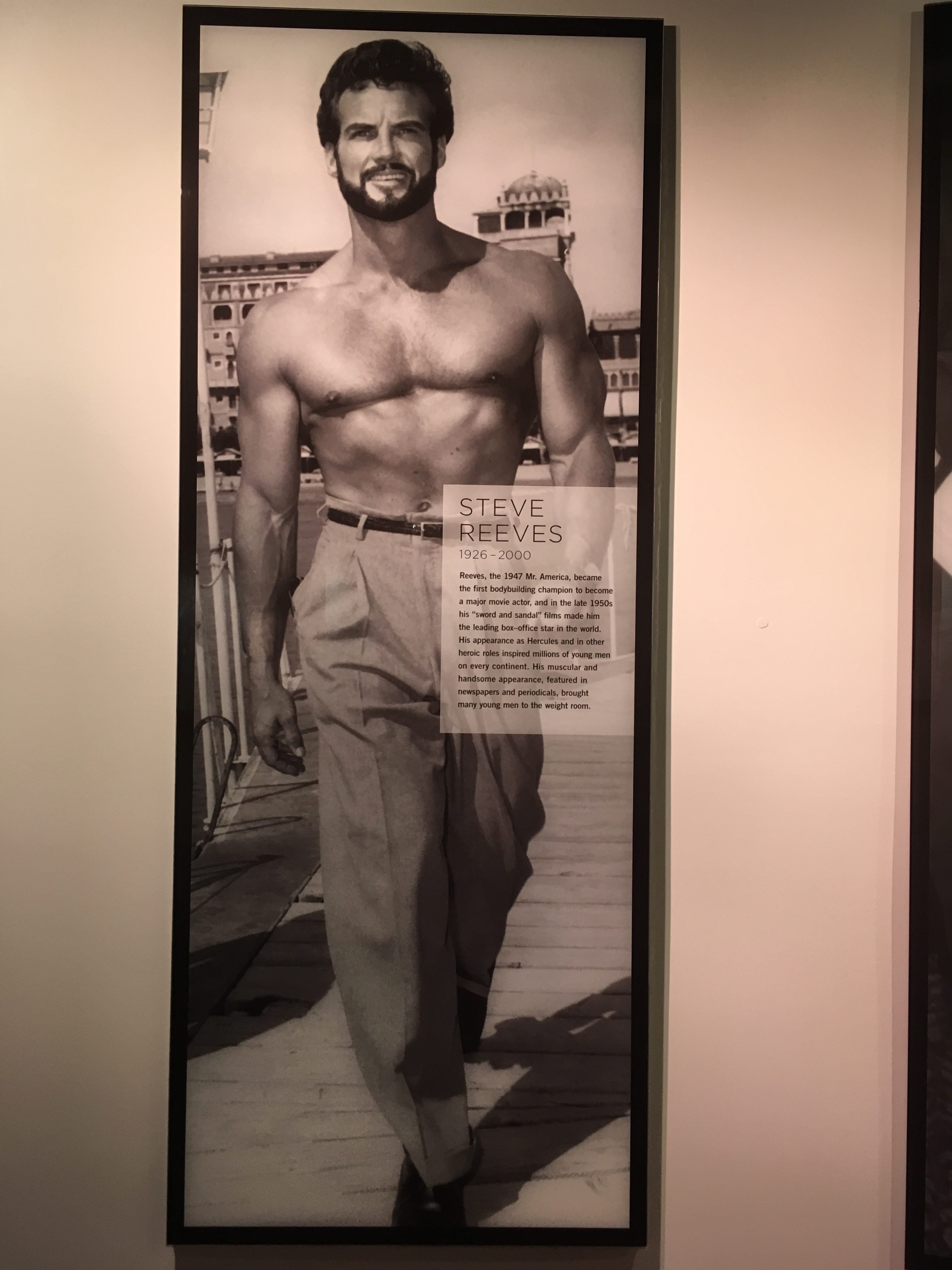

Life-size photo portrait of Steve Reeves. “His muscular and handsome appearance, featured in newspapers and periodicals, brought many young men to the weight room.”

Among the Stark Center’s collected objects of physical culture (“a term used to describe the various activities people have employed over the centuries to strengthen their bodies, enhance their physiques, increase their endurance, enhance their health, fight against aging, and become better athletes”) are the following:

- Sorin’s Monster, “a 500-pound barbell used in the first Mighty Mitts Contest.”

- Bodybuilder George F. Jowett’s lifting shoes, and his 172-pound anvil, “one of the most famous iron game implements in the world.”

- A 600-pound granite barbell that belonged to “legendary strongman Elmer Bitgood.”

- A dozen life-size photo portraits of famous bodybuilders, including Steve Reeves and Jack LaLanne (pictured with his dog Happy).

- Reproduced covers of magazines like Muscle & Fitness, Your Physique and Mr. America.

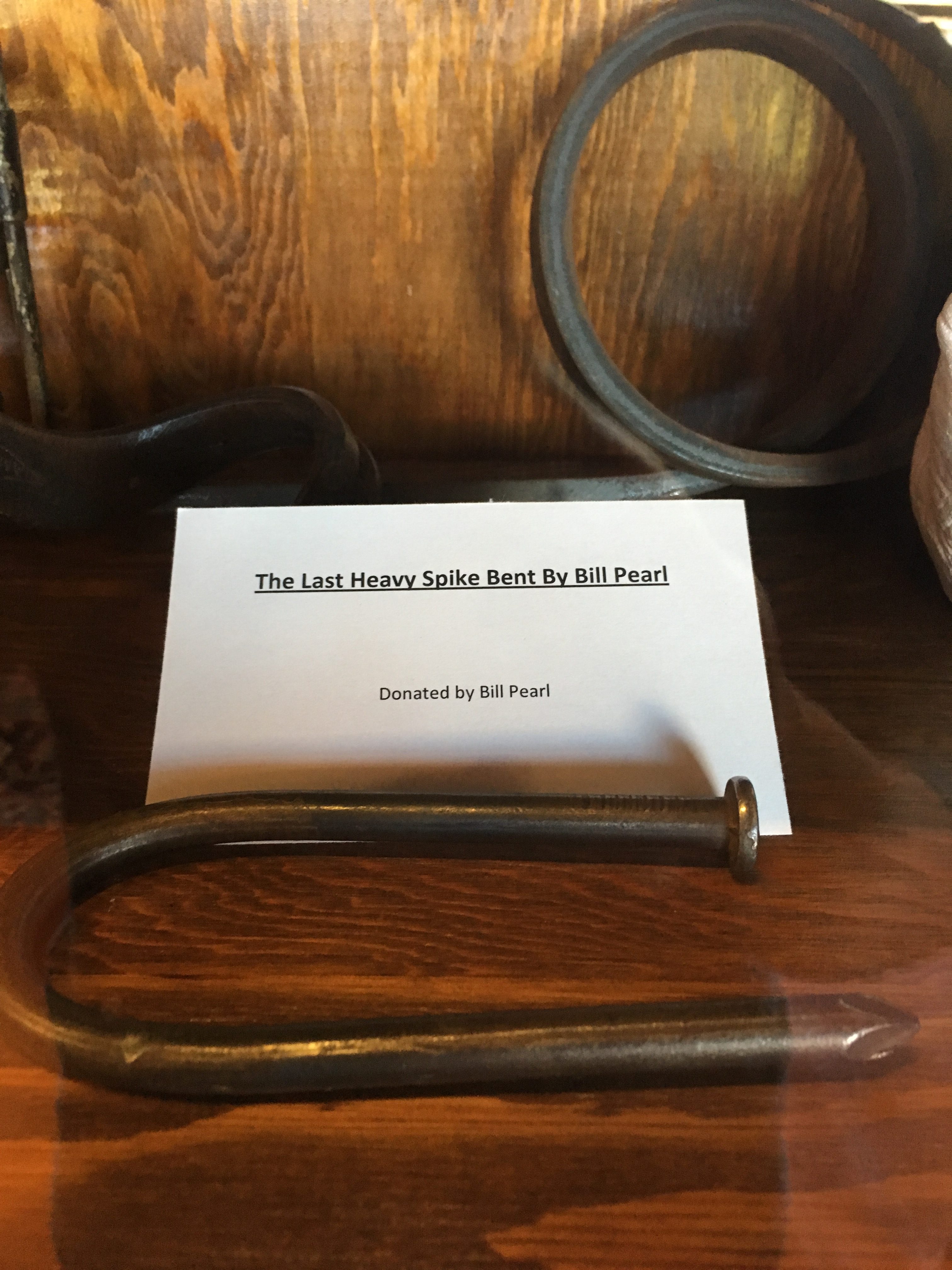

- A bookcase full of objects (iron bars, phone books, license plates) that strongmen have bent and/or ripped in half.

- A painting of Ben Crenshaw at the 1984 Masters.

- An oil portrait titled “Betty Weider in Swim Suit (artist unknown).”

Oil portrait of Betty Weider, wife of Joe Weider, who co-founded the International Federation of Bodybuilders, and donated $2 million to the Stark Center.

Promotional posters of strongwoman Katie Sandwina and also some dudes.

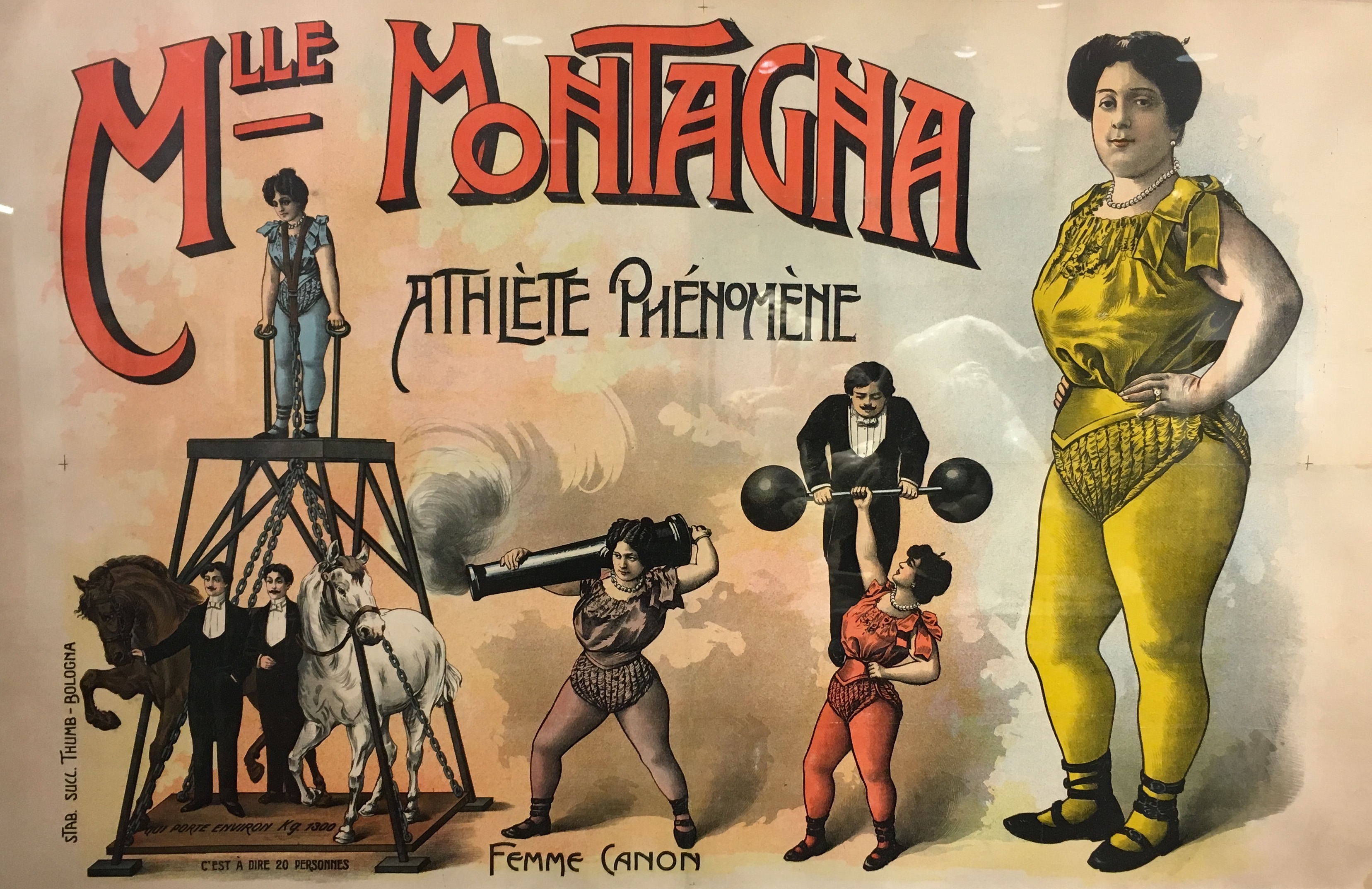

As this list indicates, the collection skews decidedly male. Turn-of-the-century strongwomen Mlle. Montagna and Katie Sandwina show up in circus advertising posters, and women are well represented in photo exhibits covering topics like Muscle Beach, professional wrestling, and golf. There is a single photo of the Center’s Director Jan Todd, the first woman inducted into the International Powerlifting Hall of Fame, executing a partial deadlight of over 1,000 pounds. But the few artifacts associated with female athletes mainly serve to call attention to the overwhelming atmosphere of masculinity. Physical culture was always primarily male culture; female lifters and bodybuilders have been regarded as aberrations from the very beginning.

Lithographic poster of strongwoman Mlle; Montagna, printed in Bologna, c. 1900.

Stark Center Director Jan Todd in 1981, completing a partial deadlift of over 1,000 pounds.

To be fair, the Center lacks the resources to display all its treasures. George Jowett’s lifting shoes, for example, require special protection from humidity and light, and so are not currently on view. There are, however, a metric shit-ton of historic barbells lying around the place (sadly, signs forbid visitors from attempting to lift them). Yet this virtually all-male world, replete with bulging muscles and iron implements, holds not even a passing reference to homosexuality. This omission is even less explicable than the Center’s gender imbalance. After all, prior to the Supreme Court’s 1962 decision in MANual Enterprises v. Day, federal obscenity laws meant that bodybuilding magazines served a vital social and economic function as proxies for gay porn. Yet the Center’s displays are relentlessly heteronormative.

Covers from just a few of the magazines Joe Weider founded. One features Weider’s protégé, seven-time Mr. Olympia Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The Center’s extensive academic archive may hold more clues to the historical relationship between physical culture and LGBTQ culture. The Todd-MacLean Library, open to researchers, comprises 36 different collections, including almost the entire run of the periodical Iron Game History, with articles such as “John Curd Edmunds: Master of the Pull-Up,” “Steroids and Monkey Glands,” and “Captain Barclay: Extraordinary Exerciser of the Nineteenth Century.” On my recent visit, the helpful staffer at the information desk assured me that the archive is indeed visited by scholars researching gender and sexuality. But their findings may be limited, according to author John Fair, whose recent book Mr. America is based in part on the Center’s archives. While researching the book, he said, he was surprised by “how much homosexuality and hustling was part of the bodybuilding culture. . . . It’s a subject that for many years was very hush-hush, and for that reason it has been very difficult to research.”

To be honest, it is a pretty big spike.

Even today, openly gay professional bodybuilders and strength sports athletes are few and far between, and bodybuilding culture is still deeply confused about the relationship between male body worship and heterosexual masculinity. Which makes all the more touching the Stark Center’s evident love and care for curating the physical form. The objects showcased here are a kind of statement of faith, that you don’t have to explicitly acknowledge sexuality, as long as you can see and celebrate the body. Perhaps, in the past, that was enough. This year, six young men are stepping up to say it’s not enough anymore. In doing so, they’re taking on a weight more formidable than any granite barbell.

Specimens from the Todd Stein Collection at the Stark Center. 19th-century fitness fads in Germany “fostered the creation of these steins in much the same way that baseball and football have inspired all kinds of collectible memorabilia.”

Alongside the giant nude Hercules at the Stark Center’s entrance are arrayed dozens of specimens from the Center’s collection of exercise-themed antique beer steins. The steins (decorated with images of brawny men, barbells, and bears, and slogans like “Kraft heil!” meaning “Hail to strength!”) commemorate the 19th-century origins of physical culture in the beer halls of Austria and Germany, where men would gather to lift weights. Then, as today, beer was in integral part of sports and competition.

Last year, during a total of six home football games, Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium collected $2.8 million in beer sales.

Hustling, it would seem, is still very much part of the culture.