The Many Acts of Keith Gordon

How does a young, successful actor become a relatively unknown director of most of the television you watch? And what’s next?

This story was co-published with Longreads.

Keith Gordon circa 2008. Photo by Rachel Griffin.

“When I first met him the only thing I really remember is that he looked familiar to me,” cinematographer Tom Richmond told me about Keith Gordon, the director and former actor. “We would walk down the street…and people would recognize him all the time,” said Bob Weide, an executive producer, writer, director and one of Gordon’s oldest friends. “He has one of those faces where it would be, ‘Excuse me, I don’t mean to bother you, but don’t I know you?’ …Keith would always give them the benefit of the doubt and say, ‘Um, I don’t know. Do we know each other?’ They’d say, “Did you go to Brandeis?’ And Keith would say, ‘No, no, no, I didn’t.’ …They’d say, ‘Wait a minute, did you grow up in Sacramento?’”

“You know what it’s like, when you see him from that time,” recalled Gordon’s wife, Rachel Griffin, a film producer and former actress. “He looked like somebody you knew.” And it was often true, sort of: many people know what he looked like in the mid 1980s, because Gordon had been a very visible, successful actor in teen comedies and thrillers.

“They would rarely say, ‘Oh my god, you’re the guy in Christine, or you’re the guy in Dressed to Kill or whatever,” Weide said. “Sometimes I would actually just jump in and say, ‘He’s an actor, you’ve probably just seen him in one of his films.’ …It was just really painful for him. People thought they knew him, but he was always way too embarrassed or humble to say ‘I’m an actor, maybe you’ve seen one of my movies’.

Maybe you have seen one of his movies, and not just one he’s starred in. Gordon has directed five feature films, as well as some of the most prestigious of prestige television, including but not even remotely limited to “Fargo,” “The Leftovers,” and “Homeland.”

![]()

In 1999, I was at the University of Illinois in Champaign, flipping around the channels when Gary Sinise’s face filled the screen. He was screaming. Not a brave war cry, but screams of terror and madness. He was wearing a helmet and bundled up in fatigues. Then there was a cut, and the camera tracked in on him from the side in a strange repeated shot. He was standing in a foxhole in the middle of a snowy field. After another cut, the camera was back in front of him. He stopped screaming and the guy in the foxhole reached up to comfort him. Gary Sinise pushed him down and pointed the rifle at him, and his friend held his hands up. The other guy was Ethan Hawke.

Gary Sinise’s scream turned to a whimper and then he pulled the rifle away from Ethan Hawke’s face and climbed out of the foxhole and started running. In a shaky handheld shot, the camera-as-Ethan Hawke followed Gary Sinise as he ran through the snow, stripping off his clothes. Gary ran into the forest and, stark naked, crouched into what must have been a freezing cold stream, and started bathing himself. This was the opening sequence to A Midnight Clear, a gorgeous, meditative, horrifying film from 1992 about an exhausted group of soldiers during World War II, adapted from a novel of the same name by William Wharton.

The film completely fascinated me. It possessed me. In many ways, it still does, as I watch it at least ten times a year, sometimes seeking inspiration, sometimes seeking guidance on good storytelling, sometimes just wanting to be in awe of something. For me, other World War II films just don’t compare. Saving Private Ryan is phenomenal in its all-too-raw battle scenes, but the film is so plot-driven, so focused on the narrative, that it leaves no room for existentialism. Even the smallest scenes are in service of the arc, or setups for dramatic character conflicts. On the other side of the spectrum, there’s Thin Red Line, a film is so sprawling it hardly leaves room for anything but the existentialism.

A Midnight Clear manages to land squarely in the center. Drenched in mood and beauty, the film is far more concerned with the human experience than armed invasions. And yet, it never meanders from its gripping plot: an exhausted and terrified unit of American soldiers teams up with a unit of even more exhausted and terrified German soldiers in an effort to execute a plan that is both brilliant and insane.

Keith Gordon on the set of ‘A Midnight Clear.’ Photo by Arye Gross.

I won’t say A Midnight Clear is the best film ever made in some universal, objective way. It’s pointless to try to convince you, because art is subjective. But it’s certainly my favorite. That night in Champaign, I watched the credits closely to see who directed it. Keith Gordon—the name sounded familiar enough, but what I didn’t realize right away was that he was someone I’d seen again and again on the television screen as a kid.

When I was nine years old, the 1986 movie Back To School seemed to be broadcast on an infinite loop. Gordon played Rodney Dangerfield’s son, a straight-as-an-arrow diver whose time at college gets pretty wacky when his outrageous father lands on campus as the latest enrollee of the school. Even back then, I recognized there was something especially dark and brooding and—though I wouldn’t have had the vocabulary at the time to say it—vulnerable about Gordon. They could have hired pretty much any actor to deliver a kind of put-upon “awww jeez dad” performance against Rodney Dangerfield’s bawdy, Borscht Belt antics. Instead, here was this kid in this ridiculous movie who looked haunted at times.

Still, nine-year-old me was far more drawn to Dangerfield (not to mention Sam Kinison as a college professor). But he stuck with me. Later, when I saw John Carpenter’s Christine, (which had come out in 1983), I recognized that same kid from Back To School. He was now playing both villain and victim: Arnie Cunningham, an underappreciated nerd who falls in love with a demonic 1958 Plymouth. This character was strange: nerdy, then cool, sweet, insecure, vulnerable, disturbed, dark, harmless, dangerous. I thought, man, now that is perfect casting.

![]()

I was hardly alone falling in love with A Midnight Clear. Vincent Canby of The New York Times noted in his review of the film that even though Gordon had only one prior film under his belt (an excellent adaptation of Robert Cormier’s private school psychodrama, The Chocolate War), “A Midnight Clear would seem to indicate that he has had far more experience.” He wraps his review up by stating, simply: “In A Midnight Clear, just about everything works.”

In the Washington Post, Hal Hinson said A Midnight Clear is “uniquely enthralling,” and “a war film completely unlike any other, a compelling accomplishment that’s more soul than blood and bullets.” After a quick plot summary, he sets his sights on the director, praising his ability to find “the emotional heart of a scene”:

Aside from his confidence with the camera and his impeccable sense of pace, his real strength is his work with the actors… And, as their leader, Gordon shows the kind of filmmaking talent that creates genuine excitement.

“People love talking about Keith,” Bob Weide assured me. “Me included,” said Weide, who worked with Gordon on Mother Night and who found much success as an executive producer and frequent director on “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” Alexandra Paul, who played opposite Gordon in Christine, ran into him two decades later in Los Angeles where she was registering voters. Paul was immediately struck by how “curious and inquisitive” he was about her life. “It was like…we had been hanging out over the last 20 years…And I really thought after that, he is the nicest person I have ever met,” she said. Tom Richmond, who is credited as either director of photography or cinematographer on every single Keith Gordon-directed film, said, “Gordon is a guy who probably cares much more about how my nephew is doing than his next movie.”

Scott Javine, Keith Gordon, and Rachel Griffin on the set of ‘A Midnight Clear’. Photo by Arye Gross.

Keith has a way of forging bonds with his actors and other collaborators that last well beyond the shooting schedule. The actor Christopher Eccleston, whom Gordon directed in The Leftovers says Keith “as much as anybody, is responsible for (among other things for the show) the establishing of Matt Jamison.” But he also told me he was already starstruck by the time he’d met him because of Keith’s own acting performance in Christine. When the two first met on the set of the first season of The Leftovers, Eccleston recalled that Keith “walked over and shook my hand and I thought ‘Wow, it’s HIM’.”

Eccleston described Keith as “gentle, honest, modest and wide open.” He said “spiritually, I felt and trusted him instantly.” Keith’s personality shone through in his direction, Eccleston explained. He remembered times when Keith “noted a tendency in me to ‘act’ and gently led me away from it and toward ‘being’.” Here, Christopher highlighted a particular scene where Keith “noted me for acting ‘jumping out of the car and running into the bank’ instead of just doing it.” Giving notes like these, especially to such an established and experienced actor, can take a delicate hand. But Eccleston said it “was done with humor and gentleness, thus preserving my confidence and saving my embarrassment!”

Arye Gross, who was in both A Midnight Clear and Mother Night spoke similarly of Keith, calling him “a wonderfully insightful and curious and compassionate guy.” He later added, “I should get together with him more often.”

“Keith is like a gem you find and you just don’t want to let go of,” said Linda Reisman, who worked with him as the executive producer on Mother Night (1996) and a producer on Waking the Dead (2000). “He’s so giving and so compassionate and optimistic,” she said, noting that these were characterizations “he would probably laugh at.”

![]()

In the years after I graduated college, I watched A Midnight Clear again and again. I moved to New York to start a band, and in 2009, we found a place in the underground New York post-metal scene. I sprung an idea on some of the other bands who we’d played shows or toured with: a compilation, using A Midnight Clear as a reference point. Everyone would watch the movie and use it as the inspiration for a song. With ten or so bands, there would be a full-length compilation’s worth of music. I envisioned that the music would organically have a similar atmosphere, tonal shifts and overall emotional impact.

It occurred to me at the time that I should try to contact Gordon, not so much for his permission, but maybe for his blessing or support. I scoured the internet and turned up his agent’s email address, and sent a note with zero expectation of ever hearing back. Two hours later, my phone rang. I answered it and was greeted by one of the most friendly voices I’d ever heard. “Hi,” it said, “this is Keith!” The warmth in his voice felt genuine.

I told him about my idea about a compilation of metal bands doing songs inspired by A Midnight Clear—which, now that I type it all out like that, sounds kind of stupid—and he loved it. Though the compilation never got off the ground, Gordon and I continued to correspond, almost exclusively over email. He was always asking about what creative stuff I was up to, congratulating me on whatever project it was I had going. He was thrilled to learn that my wife and I had our first child in 2011, and a second in 2014. In 2016, my wife and I decided to take a quick trip to LA—a romantic weekend without the kids. I sent Gordon a note to ask if he’d want to have a cup of coffee or a beer. He cautioned me about how busy he is, but said he’d try. The evening before we left, he started emailing me restaurant menus, asking which one we’d prefer.

When we arrived, I stuck out my hand to shake his. Instead, he wrapped both arms around me and gave me a big, long hug. Then he turned to his wife and said, with genuine wonder, “We’ve been good friends for almost ten years now, and this the first time we’re ever meeting in-person!” An artist who has inspired me maybe more than anyone else, an actor whose performances I’ve watched countless times since I was nine years old just called me a “good friend.” There was a part of me that just wanted to say thanks, and leave right then and there, because how could it get better? But it did. Our lunch turned into an entire afternoon, at first catching up, and then sharing stories from our childhoods, about our families.

![]() Barbara and Mark Gordon (who died in 2007 and 2010, respectively) worked extensively on the stage in New York, as well as film and TV. They were both part of the Compass Players, an improv group based in Chicago that included Mike Nichols, Elaine May, and Barbara Harris. The Gordons would travel back and forth from New York to be a part of the company.

Barbara and Mark Gordon (who died in 2007 and 2010, respectively) worked extensively on the stage in New York, as well as film and TV. They were both part of the Compass Players, an improv group based in Chicago that included Mike Nichols, Elaine May, and Barbara Harris. The Gordons would travel back and forth from New York to be a part of the company.

The Compass Players struggled with genre. Most of the members favored sketch-based comedy, but Mark Gordon strongly believed they should focus on dramatic improv. He was an argumentative and confrontational individual whose temper and communication skills, Gordon says, put him at odds with many of his colleagues and likely cost him many opportunities. The Compass Players resoundingly chose to focus on sketch comedy, so Mark and Barbara exited the group. With the sketch-comedy direction firmly established, members of the Compass Players decided to disband and start anew. In 1959, those members formed a new group, and had their debut as a sketch-comedy group at 1842 North Wells Street in Chicago. Their name was Second City.

Two years later, in February of 1961, Keith Gordon was born during a blizzard in New York City. After four years in the Bronx, his family moved to a pre-war apartment on 83rd Street between West End and Riverside Drive in Manhattan. He was an only child, and with his birth came his mother’s retirement from acting; he recalls no early desire to follow in his parents’ footsteps. Mark, continued to work, not only as an actor, but also as a theater director and an acting teacher. Among his many now-famous students was a young Morgan Freeman.

Mark Gordon’s film roles included parts in Woody Allen’s Sleeper (1973) and Take The Money And Run (1969), as well as appearances on television shows throughout the 70s and 80s (Gordon said he still gets tiny residual checks for reruns of Hawaii Five-0.) He directed both drama and comedy plays, off-Broadway and off-off-Broadway. Mostly, he did television commercials to pay the rent. “But he hated that,” Gordon recalled. “My dad was like this communist, idealist guy who just felt like he was being forced to sell his soul to sell products…And yet, he wanted to be famous and loved and didn’t know why other people he worked with were getting more attention and becoming more famous. ‘Why is Mike Nichols going and winning Oscars?’ He was never really able to resolve [that]. He made different choices [and couldn’t] accept or be comfortable with the fact that he, at the end of the day, was drawn to doing things that were blatantly uncommercial. Which is really cool, if you accept what you’re doing. But it would be like me making my little movies and going, ‘Why didn’t this gross as much as Jaws? I’m really pissed.

Gordon’s father shuttled his anger freely between his work, his home, and back to his work. “He was constantly frustrated, angry, and bitter outward and inward…It was very difficult to grow up with because was angry all of the time,” Gordon said. “My dad was constantly getting fired. I’m sure some of it was their fault, which he always made it. But if you’re getting fired a lot, you sort of sometimes need to stop and look in the mirror and ask, ‘Is it something I’m doing?’ And he just never did. For him, it just became one more argument that the world sucked and people didn’t respect him and people didn’t understand art, instead of ‘maybe I’m just being an asshole’.”

Gordon’s father also earned a reputation as a notoriously difficult director. He directed Keith once, and only once, in a 1976 production of Tony McKay’s three-character one-act, A Traveling Companion. “The play itself was terrific,” Keith remembered, “as were the two other actors.” But for Keith, it was an object lesson for how not to be as a director. “I remember even thinking at the time, ‘If I ever direct, I don’t want to act like him’ because he made me feel small all the time, and I watched him make the other actors feel small and feel stupid for not seeing things his way,” Keith recalls. “And I remember just thinking, ‘this is horrible’.”

Mark never lost an opportunity to criticize his son’s performances. In 1975, Gordon said had his very first television appearance “at 13.” And he clarifies, “I wasn’t even an actor.” Nonetheless, through his parents’ friends, he got word that the CBS medical drama, Medical Center, needed someone to play the role of a boy dying of leukemia. “I auditioned, I got the part, and it was great, it was fun, it was wonderful, but I wasn’t trying to be a professional actor; I just got to have this experience,” Keith told me.

When it aired, Gordon’s father was out of town working. “He just called and immediately started in with the criticism. He didn’t even say ‘that was great’ or ‘that was cool’ or ‘it was so exciting to see you on TV.’ It was just like ‘Well, you know I really feel like you didn’t take researching the disease seriously enough. I felt like I could tell you really didn’t know what the symptoms you were dealing with were.’ Somehow that just crystallized something about the whole relationship. That, at 13, that’s what his reaction to it was. And I remember just feeling really crushed and really feeling like, ‘Okay, I’m sorry I failed.’”

Gordon had been an excellent student, and 1971, as a fifth grader, he left the New York City Public School system and went to the prestigious prep school, Dalton, thanks to an academic scholarship. By the time he was 16, Keith had been working so frequently (the production of Jaws 2 lasted nearly a full year) and earning his credits remotely, that the school told him he either needed to come back and finish in the classroom, or leave the school altogether. So, at age 16, with his professional acting career well underway, Gordon dropped out of Dalton and moved into a studio apartment on West 72nd Street, the rent $350 per month. “I’d been able to save a lot while doing Jaws 2. I had no rent or other major expenses while I was doing that for 40 some odd weeks, so even at SAG scale (I think about $600 a week then), I was able to have a pretty good sized bank account for a kid of 16 when I came home,” he said.

“I felt so cool, I felt so ‘fuck the world’,” Gordon recalled. “At 56, I look back at my 16-year-old self and think A) where did you get the balls? And B) You really had no idea that was such a risky choice, did you?” While he couldn’t escape the critical views of his father, he was able to get a break from them, and from the anger, and from the generally dysfunctional relationship he had with his mother.

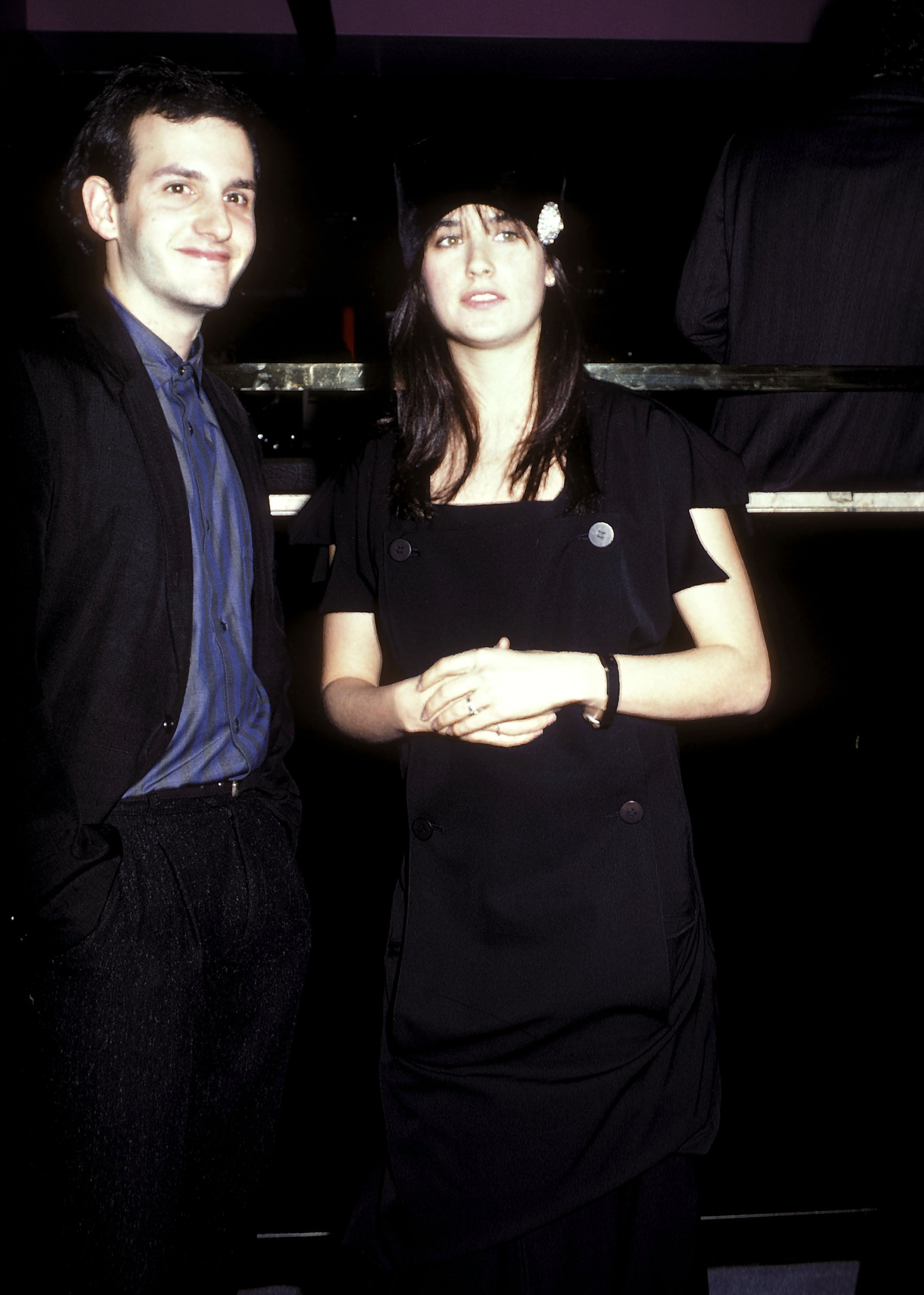

NEW YORK CITY – OCTOBER 30: Actor Keith Gordon and actress Demi Moore attend “The Early Girl” Opening Night Party on October 30, 1986 at Club Monaco, 41 East 58th Street in New York City. (Photo by Ron Galella/WireImage)

When Gordon moved on to directing, his father’s criticism became only slightly less brutal, in large part because Gordon simply stopped engaging with him. “I…didn’t let the conversation go there. I mean, he would start lecturing me about things I had done wrong, and I would just sort of change the subject. I think at age 35, 40, 45, 50, I kind of learned, ok, my dad is my dad; he’s not going to call up and go, ‘God, A Midnight Clear was so wonderful, I love you so much, I’m so proud of you’.”

“He could never come see me in a play or whatever and say, ‘that was great!’ He had to like talk to me, until I finally walked away, about everything I did wrong…I mean, he would come to plays and just give me hours of notes, and I’d have directors go, ‘you can’t talk to your father because when you do, you come back here and start changing your performance.’ It was really inappropriate and weird.”

Even as he tried to disengage from his parents about his work, Gordon’s parents were eager to talk to about the reviews his films were getting. “That was the other thing about my parents that drove me insane,” Gordon said. “They were so outer-directed. Like good reviews, that really meant something. That meant you were good… They were obsessed with reviews. They would save reviews, they would get reviews from all over the country.”

On the other hand, he said, “of course they would always make sure I knew about every bad review. They would call up and say, ‘Did you read this thing in the Des Moines Register?’ ‘What thing in the Des Moines Register?’ ‘Well it said you’re really terrible and you have no talent and you should never make another movie.’ ‘No, I didn’t read that.’ ‘Yeah, no, let me read it to you!’ ‘No, I don’t really need to—’ ‘Well, I’ll send it to you.’ ‘No, you don’t need to send it to me.’ And then it would be there in the mail three days later.”

But Gordon also credits his father for much of his own talents. “I got a lot of my strengths as an artist from him. He was amazing in terms of breaking down a script and analyzing characters and why they’re doing what they’re doing and what the writer’s real meaning was…he was so obsessed with it. That was his religion—theatre and art.”

![]()

I was feeling good when my wife and I returned from our trip to LA and our afternoon with Keith. I had been working on a big feature for “This American Life,” and was all set to finish it up. Instead, I got word the story was being killed. The following day, I got congratulatory calls from friends and family around the country who heard a teaser for the story on “This American Life” promos. I had to explain to everyone it wasn’t going to happen. I was gutted.

I poured my heart out to my wife. But there was someone else’s shoulder I wanted to cry on: Keith’s. He knew how important this was to me; we’d talked the story over lunch. And he was excited for it, as it touched on something we’d talked about: father-son relationships. Keith of all people knew how cruel the creative world could be. He would understand better than most, I reasoned.

I sent him an email explaining what happened, and eagerly awaited his sympathetic reply. That same day, he emailed me back. It started out positively enough. “Hi!” he wrote:

So sorry this has been a nightmare in dealing with “the system.” Sadly that’s been more the rule than the exception in my experience… But the one thing you can’t do (much easier said than done) is to turn “development hell” into an internal referendum on the value and quality of your own writing.

It will kill you, and undermine you…

What you are describing is certainly typical of, say, what most scripts go through when being developed at a studio.

It’s maddening, hurtful, destructive, stupid. But it’s not a reflection on the quality – or lack thereof – of a script.

Turning this absurd process inward – other than when you cool down seeing if there are any points that feel actually useful to you – is generally not the way to survive it.

It wasn’t the warm embrace I was expecting or hoping for. His message seemed immediately clear: I needed to stop whining and get used to setbacks like these if I wanted to be doing this for the long haul. Just days earlier, he had spent an entire afternoon telling me about all the conflicts and confrontations that he had to go through with his parents throughout his entire life. And yet there was one very obvious attribute of Keith’s that I had completely failed to recognize: the guy is tough. Keith Gordon is remarkably resilient.

In addition to how brilliant Linda Reisman thinks Gordon is as a director, she’s particularly impressed by how practical Keith is, how well he understands how the business works, and how he seems to not let it get him down. “This could be a gross exaggeration,” Reisman said, “but maybe 90% of what we do is dealing with rejection of some form or another.” She remembered a time in the mid ’90s when she was trying to get Affliction off the ground, but struggling to secure financing, and grappling with other issues like casting. “When we finally got that movie made, I remember saying, ‘I will never do anything that’s this hard again.’ And everything I do is like that.” Linda says that “it is harder and harder to get movies financed,” and that “the film that I just made took ten years. A film that I was involved with before The Danish Girl took twelve years. Some of these things just take forever.”

Speaking of which, why hadn’t there been a new Keith Gordon film in fifteen years? What’s he been up to all this time?

![]()

Keith Gordon is now deep into the third wave of his career: television directing. In 2017 alone, Gordon directed episodes of “Better Call Saul,” “Fargo,” “The Leftovers,” and “Homeland.” His other credits include “Dexter,” “The Killing,” “Nurse Jackie,” “The Returned,” “Rubicon,” “Masters of Sex,” and “The Strain.” As with his father, there was a financial reason he turned to television. But unlike his father, Gordon has not had to sacrifice his own sense of art or identity as an artist to do it. But television is different from film. On a television show, the director works within existing frameworks—the look, the characters. In most cases, they don’t even have a say of which episode they get to direct. In fact, because producers have to be protective about plot developments and characters’ fates, directors are often not even told about what has transpired or will transpire in the preceding or subsequent episodes. It’s like directing with blinders on.

And yet, Gordon finds the work creatively fulfilling, and he has a real sense of glee when he lands a gig on a show he loves. Part of his success is his easy, natural resilience, his way of navigating a business that where there are far more red lights to be found than green ones. Gordon recalled that when he was getting started, “getting feature directors to do TV was still a big deal.” Back then, “TV overall still hadn’t really blossomed, but feature directors were starting to do the rare special, more cinematic shows.” He added, “it wasn’t just that feature directors turned their noses up at TV—though most did—but the networks were also petrified that feature directors wouldn’t be able to deal with the tight schedules and low budgets of TV.” This made Keith Gordon an attractive prospect for the job. “The fact I came out of low-budget indie filmmaking certainly helped them see me as less of a risk,” he said.

Early in his television directing career, the offers came his way without him seeking them out, and he soon found himself directing episodes of “House MD,” “Gideon’s Crossing,” and “Night Visions.” He had read about “Dexter” and thought, “the concept was amazing and so out there, so I got my agents to get me a copy of the pilot, which I thought was incredible on a filmmaking level as well as a story one. I told them I wanted to try to get on it.” His agents managed to get him a meeting. But word came back to him that the directors were already booked. Undeterred by the news, Gordon asked for a meeting anyway. “In case there was a season 2, I’d be on their radar.”

“The meeting was great, and I think they got how passionate I felt,” Gordon said. One of the show’s executive producer (and the director of the pilot episode) Michael Cuesta, was a fan of Gordon’s films. When a director dropped in season one, they called him last minute. With little time to prep, Gordon took the opportunity. “It went well, and so I did nine more [episodes] over the rest of the run.” As recurring and frequent director of such a critically acclaimed and successful show, Gordon’s stock as a television director rose sharply. “Once I was a running director on a critically lauded hit show, I started getting a lot of offers for other things,” he says. But Gordon was not content to just take any job—he wanted to work on the ones he could feel truly satisfied by and proud of.

In spite of his cachet, Gordon said, “I still would chase things I thought were special, and pass on things I didn’t. ‘The Killing’ only happened because I chased it.” He ended up directing three episodes of the show. He was also the one who pursued shows like “Homeland,” and “The Leftovers.” “But once I was established, chasing was much easier. If my agents knew I loved a show they could usually at least get me in the door for a meeting without much trouble.

“Without much trouble” is a rare expression for an industry like the one Gordon works in.

![]()

Gordon’s last feature film, The Singing Detective was an adaptation of a 1986 BBC miniseries of the same name. It got mixed reviews when it came out in 2003, and hardly made any money at the box office. Of course, it’s hard to imagine that a somewhat surreal, film noir, musical crime comedy would. But his previous four films (all of which are adaptations of novels), Waking The Dead, Mother Night, A Midnight Clear, and The Chocolate War, were all met with critical accolades, even if their box office numbers weren’t spectacular.

In fact, his first movie, The Chocolate War, didn’t make much money ($300,000) at the box office in part because it was never intended to. Gordon said that a significant part of the film’s distribution was him researching and looking up theatres in cities, then just calling them up and asking if they wanted to screen the film. More to the point, the film was financed because the backers knew that the money they’d make on it would be from the rental market, which, in the late eighties, was a huge part of the business.

THE CHOCOLATE WAR, Ilan Mitchell-Smith (c), 1988. (c) MCEG Productions

Because the film was an adaptation of a novel taught in a large number of high school English classes across the country, it was likely to get even more business in the rental market from both students and schools. The $500,000 budget was minuscule as feature films went, even then. In a special-feature interview on The Chocolate War DVD, Gordon says he told the investors, “there’s really not a lot of risk there because if I give you something that’s in focus, that’s basically vaguely professional, you’ll make your money back.” They believed him. And, he was right.

Box office performance is largely out of the hands of directors anyway. “I think in terms of the indie film business, it’s the luck of the draw when something comes out and how much [of an effort] the distributor puts an effort behind it,” Rachel Griffin said. “A Midnight Clear opened in LA the weekend before the Rodney King riots. There was a curfew in LA. When has there ever been a curfew in LA?”

I had been assuming that other people were the reason Gordon hadn’t made another film. That it was a matter of financiers and investors unwilling to back a director who hadn’t put up big numbers at the box office. “This is thing with Keith,” Reisman said. “He’d rather make that original vision that may be too literary that may be too dark or that’s harder to put in a box for a lower budget than that big budget studio movie. Keith has had many opportunities to cross over that I’m aware of. He made choices. He said, ‘I don’t want to be a movie director for hire.’ At least from what I know. I haven’t discussed this with him recently. You’d have to ask him. But from what I know, Keith basically said, ‘I don’t want to do that. I want to keep my integrity, I want to keep working on my independent projects, I want to have choices’.”

Gordon does want to direct another film, and is actively trying to make it happen. But he only wants to make the films he wants to make. “I have tried to work with Keith many, many times since [Waking The Dead],” Linda tells me. “I’ve sent him things. He’s very picky. He’s very particular about what he wants to do.”

![]()

Gordon has always been particular—even as an actor, he had strong preferences. Perhaps the best example of this is the 1986 film called Static. Gordon portrays Ernie Blick, a charming, optimistic, potentially delusional young man who has dealt with the death of his parents by inventing a machine that he claims will allow people to see heaven. This is Gordon at the top of his acting game: he’s all charm and smiles on the surface, while always, in the most subtle but effective ways, telegraphing his grief, his naive optimism, and his tenuous grip on reality. In one pivotal scene, the mask slips, and he explodes in pain and rage that feels so authentic, I have to wonder what kind of personal slights he was drawing from in that moment.

This utterly bizarre, beautiful, very funny film is important for another reason: it represents Gordon’s debut as a screenwriter and producer. It was directed by Gordon’s best friend at the time, Mark Romanek, the highly successful music video director, and also director of One Hour Photo (2002) and Never Let Me Go (2010). Frustratingly, Static has been (officially) unavailable for a very long time. If you go Googling, you’ll likely read that Mark has “disowned” the film because he dislikes it so much. In high school, I’d seen some clips of the film on a VHS tape one of my movie-buff friends had, but I’d never seen the full film. In speaking with Gordon and others, it became clear that not only is Gordon still proud of the movie, but that everyone really likes it.

I went online and bought a bootleg DVD of the film. Despite the poor picture quality of the transfer (which looks like it was put on DVD via third-generation VHS copy), it’s immediately apparent that the film is visually stunning—the colors are ultra vivid, the shots are framed and composed in a way that makes the viewer immediately experience detachment, isolation, terror, freedom. In one scene the camera pans across a wall adorned with deformed crucifixes. (Ernie works at a crucifix factory and steals the faulty ones.) It’s gorgeous, frightening, heartbreaking, mysterious.

Beyond the visuals, the story, the acting, the atmosphere, everything about it seems at least ten years ahead of its time. Aside from some festival showings and a few screenings in the UK/Europe, the film got hardly any play in US. In fact, it was only shown one screen in New York: at the Film Forum’s previous location on Watts Street. And it’s not available to rent or stream or buy because Romanek himself owns the rights and does not want it to be available to the public.

Romanek and Gordon met in late 1977 when they both had the opportunity to work with director, Brian de Palma. “Brian de Palma invited me to come out to Sarah Lawrence to work on a student film. I worked as the second A.D. Keith was the lead actor and we became best friends,” Romanek told me, referring to Home Movies, a rather strange film from 1980 that was both a real film but also, as Romanek puts it, “a student film.” De Palma oversaw the entire production, but he had his students make the film—all aspects of it. As Romanek said, he was second AD. Gordon played the role of Denis Byrd (a character that de Palma reputedly based on himself).

Gordon and Romanek clicked creatively and wanted to work together on another project. So, over the next few years, they sent ideas for a film they could make together. In the meantime, Gordon was also landing higher profile acting roles (including working with de Palma again in Dressed to Kill). By the time, they had the script and financing squared away for Static, Gordon had honed his acting chops. But as for Romanek, he says he knew “fuck-all about directing.” He told me the extent of his direction was that Gordon “sort of did the scenes and I made a few suggestions. That was about as deep as it went at that level of my ability,” Romanek said. Even on the pretty poor-quality bootleg I have of the film, Static is a striking visual movie that manages to keep up a compelling pace while creating and maintaining a surreal atmosphere. Put simply, the direction is strong.

Romanek denies disowning the film. “I just find it an extremely embarrassing, amateurish effort. It was very sobering and difficult for me to realize that I had no idea what I was doing on the set. And the resultant film for me is detailed evidence of that fact. I got it in my head that any respectable director needs to direct a feature film before he or she was 25 years old. Maybe that worked for Stanley Kubrick and Orson Welles, but it certainly didn’t feel like it worked for me. I just wasn’t ready,” he explained.

It’s one thing to have a great idea that doesn’t get realized. But it’s an entirely different one to have it realized, but have it be hidden from the world by the very person you worked with to create it. You would think Gordon would feel bitter toward his old friend, Mark Romanek. You’d be only half-right. When Keith does express his disappointment at the film’s unavailability, he does so only by paying respect and admiration for Romanek. “I think I’m just sad because I think Mark did a great job and I think he made a really amazing movie…I think he made something really good. And I would love for him to feel good about it because he did a great job,” he says.

![]()

Gordon and Griffin live in a not-small, but not-at-all large art deco-style house in the Westside area of Los Angeles. Displayed prominently in their entryway is a very big poster for Static, and a prop from A Midnight Clear. It’s a cephalophore: the statue of a saint holding his own head, and it’s one of the most striking images in the film. We walk into the house, and they start apologizing profusely: They’ve just had some work done to their house, including having all of the interior painted. Most of the furniture is moved away from the walls. Everything is in piles on the floor, including an absolutely huge mountain of DVDs that includes big-budget films, indies, foreign films, everything. Gordon will often watch two films per day, and nearly everyone I’ve interviewed for this piece swears that Gordon may be one of the most cinematically knowledgeable people they’ve ever known.

The cephalophore in Gordon and Griffin’s home. Photo by David Obuchowski.

I sat down on a chair in the living room, and he took the couch. At first it was all small talk—good beer, and cars, that kind of thing. Then we started down the rabbithole of discussing our experiences working on creative projects, me with writing and music, him with filmmaking. This brought up a broader topic, which I’d return to a few more times throughout our conversations: success, and how he’s redefined what that means to him over time; how success in a professional sense should not be confused with success in life as a whole.

“I’ve gone through some bad patches,” Gordon admitted. “In my 30s, I went through a real crash. Interestingly, it really happened coming off Mother Night. I think I’ve had a lot of these issues my whole life, but I never defined it as depression. I knew I had anxiety issues and all sorts of other things. But I think that was the first time I had a clinical depression as opposed to being blue.”

Mother Night came out in 1996. Gordon would have been 35 years old at this time, and one would have thought he’d be riding high. A Midnight Clear came out in 1992 to universal acclaim. For Mother Night, he was working with a dream cast of actors, some of his favorite crewmembers, and his old friend, Bob Weide. Even Kurt Vonnegut was enthusiastic about the project, Bob Weide told me.

“Ironically it was because things were so good. That’s the paradox. I made this film. It was a film I wanted to make. I made it with my best friend, Bob Weide, wrote the script, we produced it together, I directed it. Linda Reisman, a great friend, was another producer on it. It went really well. It was fun. I loved Nick Nolte, I loved all the actors. Nothing was wrong,” he said.

But once it was all wrapped, and he was editing, he said, he felt suicidal. ”I felt like, okay, I’ve just had the perfect situation, I don’t know if I’ll ever have this situation this good again, and it didn’t solve everything. So why get up in the morning? I’m never going to stop feeling bad, so I give up. I quit.”

Gordon had on a congenial smile until this point in his story. But here, it fades. And in this fleeting moment, he’s Arnie Cunningham from Christine again, or Ernie Blick from Static. Vulnerable and raw. But he’s also comfortable with himself and who he is. And without any hesitation, he dove into the possible origins of such depression. “My family was very results-oriented. My family was like achievement and all that. So I always sort of clung on to this thing about if I’m not happy, if I’m not feeling okay about my life, [that] when I got to do the thing I really wanted to, then everything would be okay. So it was devastating to realize that wasn’t the way it was going to work.”

Ever resilient, Gordon, with Griffin’s help, sought to change. He saw a counselor, he started taking medication, he started meditating. He feels better. But he also acknowledges that, “it’s not like I’ve solved those issues. I just feel smarter about them now than I used to feel.” He still wrestles with feeling depressed. But he also looks at his life through more than the lens of a movie camera. He works to find joy in the smallest things, like the squirrels that he feeds in his backyard. “it’s a perspective thing, and it’s something I grapple with all the time. And, you know, I make progress but it’s still an ongoing slog. And it probably always will be.”

Gordon returned to smiling, and we moved on to discussing Waking The Dead and how he was able to coax such believable, affecting performances out of his stars. He considers it the most personally meaningful film to him—it was when he and Griffin got engaged. Moments later, Griffin came in from the other room and brought Gordon a tall glass of water. “I could hear you coughing from the other room,” she said. She’s right. We’d been talking so much, it was starting to wear on his throat.

Gordon looked at her in almost disbelief. “You brought this for me?”

“Yes,” she said.

A huge smile spread across his face, and he thanked Griffin profusely, as if instead of a glass of water, she had brought him a new car or financing for his next film. “I love you so much,” he said, and he looked at me as if to say, “Can you see how lucky I am?”

![]()

Linda Reisman said “honestly, I would give anything to work with Keith again because I think he’s just enormously talented. Not only that he’s just an amazing person to be around and learn from.” And then she adds that Keith is an “extraordinary director.” Tom Richmond, Gordon’s cinematographer, not only thinks Gordon is a brilliant director from an artistic standpoint, but that for Gordon to do another movie just makes practical sense.

“One thing that’s mind-blowing to me, having now shot as many movies as I’ve now shot, is that one of the things that I think producers should be looking for is somebody that they can guarantee that the product will be done on-time and on-budget,” Tom says. “And he’s proved that on every movie he’s made.” Tom said that A Midnight Clear was such a difficult movie to make that, “I don’t think half the directors I’ve worked with could have even done the movie.” Ultimately, he tells me, “if Keith Gordon has a slightly marketable story, hire him in a second, because I guarantee you we’ll get the movie done as planned.”

It’s not like he’s been idle. Rather, he’s been directing some of the most respected television there is: “Fargo,” “The Leftovers,” “Better Call Saul.” This has increased his cachet so much that, recently, Entertainment Weekly published a column with this headline: Star Wars: Episode IX: Consider Keith Gordon for new director. The entire piece is an impassioned argument by Anthony Breznican that Gordon should be chosen to direct the next Star Wars. But it’s unlikely next movie will be some box office behemoth. It’s more probable that it’s an off-beat indie that only plays in a few theatres. But I know it will happen. That’s not the mystery.

The mystery is if Keith Gordon is successful. As an actor, he was highly recognizable. Only, people never recognized him as an actor—they thought he was somebody they knew. As a film director, his films are breathtaking, but they haven’t been the big indie breakouts, nor have they made the kind of money that big distributors and studios hope for, and it’s been 15 years and counting since his last one. As a television director, he’s directing the best television there is to direct. But while Gordon clearly loves it, he also concedes that those aren’t his projects. Someone else is writing them, and he’s working within an existing framework established by the showrunners.

I put the question to Gordon as plainly as I can: what is success, and does he think he’s successful? “Boy, that’s a good question,” he tells me. He thinks about it for a moment as if it’s something he’s never really been able to figure out, but then he assures me, “it’s not like I’m confused about it.” “Really success to me is about what makes you happy. It’s not about an objective standard. Making 100 million dollars isn’t something I care about particularly. So if i did that, it’d be fine, it’d be great, it’d be nice to have 100 million dollars. But it’s not like that would make me feel like oh now I’m a success if I wasn’t excited about what I was doing.

But there’s bigger, more macro success that Gordon is also concerned with. He calls it “life success,” and he defines it as “a mix of things. Having enough money to live okay, and to live the way I want to live, which I’m doing; working on things I find exciting, and rewarding, and have fun. The older I get, the more I care about having fun doing it. When I was younger, I think there used to be more of a joy in the misery of art. The older I get, the more I’m like, ‘Eh, life’s short. I don’t want to be miserable.’ And then part of the bigger success has nothing to do with the outside; it’s internal.”

Earlier, Gordon had told me that more than how to break down a script or a character, the biggest lesson his father had taught him was that it was never too late change, to let go of the darkness and be a happier person. He says that when he can appreciate his marriage, his simple lifestyle, and the work that he does have, “that, to me, makes me more successful. If I’m in a mood where I don’t appreciate those things, where I don’t relish what is good, then whatever the outside standards are, it doesn’t matter, because I’m not enjoying it.”

Before our hugs goodbye, I told Gordon that I feel guilty about something. He made my favorite film in the world. And then he took a chance and called me when I contacted his agent. And since then, almost ten years ago, he’s been listening to the music I send him, reading the articles I send him, and he’s been listening to me grouse about my failures as a creative, and he’s been giving me encouragement and guidance on how to cope with those things. And here I am now, in his house, recording the most intimate details of his life, exposing his demons, so that I can turn it into something with my name on it.

In short, for all he’s done for me, what have I ever really offered him as a friend? Gordon smiled broadly and answered immediately, as if he’d somehow been expecting the question. “The thing you’ve given me,” he says, “is the fact that my work meant a lot…. There’s nothing that comes closer to defining success than inspiring another artist.” It’s another moment worth marking: Gordon calling me an artist; a person who I consider to be one of the greatest living creatives considers me a peer. “There’s nothing more rewarding than having another artist say ‘your work inspired me’,” he said.

And it has. And I am sure it will again.

Keith Gordon and David Obuchowski in 2017. Photo by Ilan Mitchell-Smith.

David Obuchowski is an essayist and fiction writer whose work has been featured in Jalopnik, The Awl, Syfy, Deadspin, Gawker, the Kaaterskill Basin Literary Journal, and others.