Bad Farmer

A snapshot from the country.

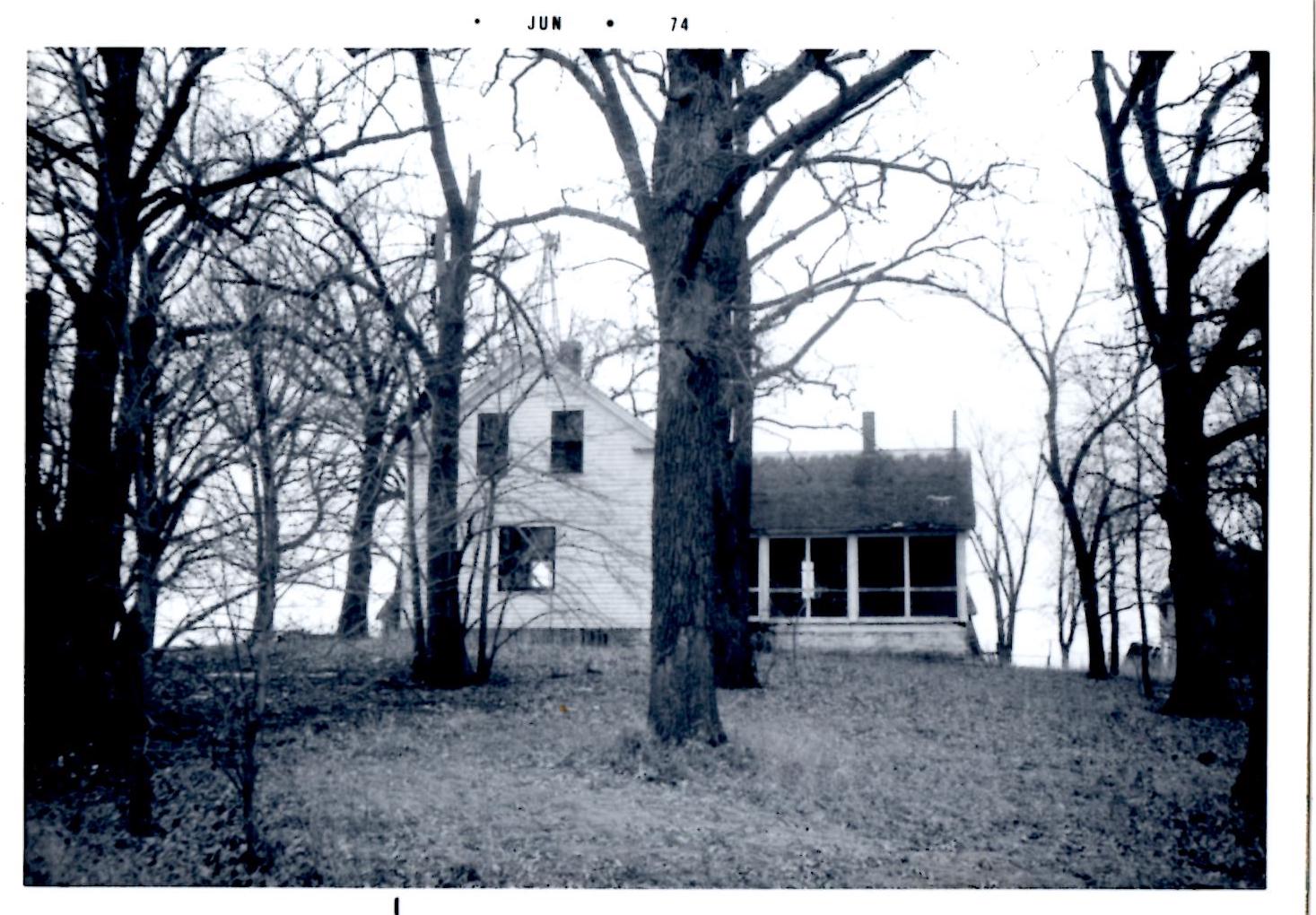

The farmhouse. All photos courtesy of the author.

Here is my earliest memory: my family is in the kitchen of the farmhouse where we lived before I was five. It’s late afternoon, but dark, because there’s a terrible storm outside. It could be a tornado, I’m not opening the door to look. The door is one of those flimsy aluminum jobs, and I brace myself against it as ferocious winds tear at our house. It won’t close properly, and I am holding it shut with the supernatural power of my tiny three year old body. We’re talking Wizard of Oz type weather, and I’m doing my part to protect the family. I’m not sure what the rest of them are doing, probably holding something down, but I’ve got the door thing handled. Just me. I’m on the door.

I don’t know. It doesn’t sound right, does it? I mean, I was three. You’d think the job of holding a faulty door closed against a tornado would have gone to maybe for example an adult. At the very least one of them could have been my spotter in case something went awry. I have some doubts that this memory is completely legit. Maybe it was just a dream I had when I was three. Or maybe I was playing some sort of game after having watched, perhaps the Wizard of Oz and was braced against a door on a sunny afternoon, yelling heroic things across the room to my family, who sat calmly eating cereal at the kitchen table. This whole moment in time can’t be trusted.

So maybe this is my earliest memory: My brother and I are leaning out an open window on the farm where we lived before I was five. We are attempting to break the sound barrier by screaming for our parents. There is blood dripping aggressively onto the windowsill, and I’m pretty sure it isn’t mine. That’s the memory; the view of tall grass and distant fields, the sound of two children screaming, the anxious feeling that spilled blood provokes. This memory has corroboration. My mother tells me that one day while she and my father were out in the field, I took a three foot statue of St. Anthony and cracked my brother over the head with it. They never heard us. They just returned to the house to find spatters and little bloody footprints trailed about the house. He was rushed to the hospital. Sounds like something I’d do.

We didn’t live on the farm for long, just a couple of years. We were brief experimental farmers in my father’s life long quest to abandon whatever he was doing. This wasn’t his first escape project. Before I was born he hauled my mother and infant brother deep into the north woods to live in a cabin. I hear there was a hole in the ground with a log over it they used as a bathroom. There are stories of mosquito infestations that rivaled biblical locust swarms. I dodged a bullet on that one by not yet being born. They moved back to the city when my mother got pregnant with me. She wanted to be closer to amenities like babysitting grandparents and plumbing. But dad was soon bored again, so he dragged us all to the country to become salt of the earth.

My brother and I brushing our teeth, possibly in the window that later filled with blood.

He was a brilliant, creative man who was raised by a chain-smoking cocktail waitress and an abusive stepfather who kicked him out of the house at the age of fourteen. His family tree was riddled with alcoholism and violent men. He was driven by grand aspirations but haunted by doubt and failure. And he was a terrible farmer. Raised in the city himself, I can’t imagine he’d done much research on the subject, just bought a parcel of land and winged it.

And much like the condemned house we later bought and renovated that dropped little chunks of molding as if it had leprosy, the details showed the flaws in his plan. There were no food crops, aside from a little vegetable garden my mother kept, but you don’t need a whole damned farm to grow a few vegetables. He did however cultivate a great deal of pot he stored in big black garbage bags in the attic that made my mother terribly nervous when the sheriff came around. This was a regular occurrence, the visiting sheriff. But he had no idea what was in the attic. He was actually there to talk about the cows.

The neighbor farms grew a lot of corn. When they harvested, there would be cobs left on the edges and corners of the fields. Our family would go gather all the strays to feed the cows.

This wasn’t a very professional setup. We had livestock, but they were tended to in a lackadaisical and haphazard way. Billy the sheep was tethered to a stake, enabling something to effortlessly eat his leg one night. We woke the next day to find a wooly tripod standing in the yard. The chickens were stuffed in a little shack with no shelving or beds. During a thunderstorm they ran together in a terrified clump and smothered themselves. After disposing of the bodies, dad didn’t renovate their coop. He just gave up on raising chickens. The barn was infested with bunnies. They had few cages, just hopped around free multiplying until a visit to their habitat became a Hitchcock scene.

The cows demonstrated the most problematic of my father’s innovative agricultural techniques. He didn’t have the patience to build fences, so they roamed free. He just slowed them down by tethering them to heavy things. Then the sheriff would have to come by from time to time to tell us our cattle were wandering the neighboring fields. They were unmistakably ours, as they were dragging the cinderblocks and tree stumps my father had tied to their necks.

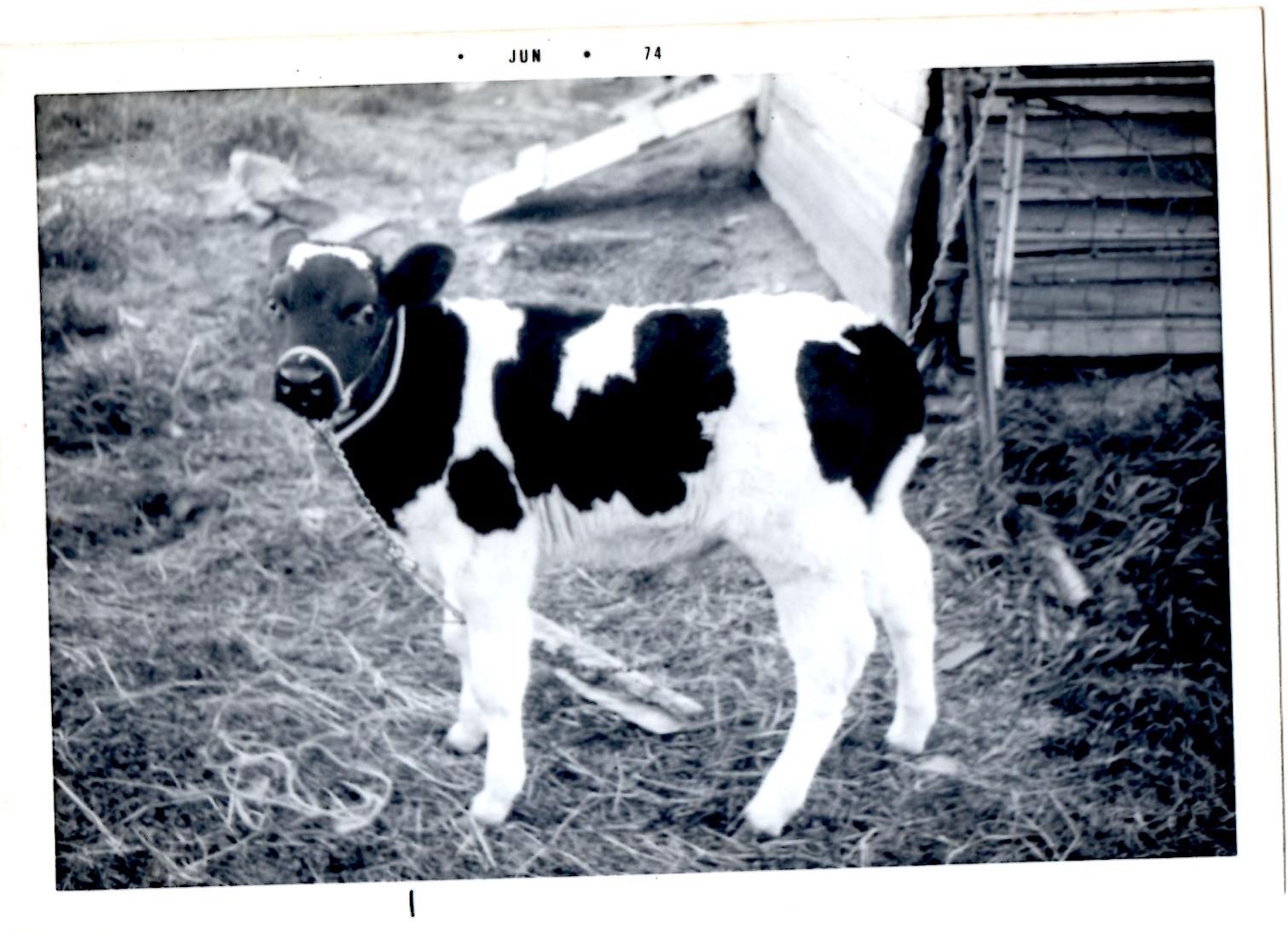

Me with a cow behind one of our rare fences.

I have to wonder what the neighbors thought. Did they shake their heads and mutter, “those damned Sheridans” every time they found a cow dragging a tractor battery through their soybeans? Did they think we were insane? This was the mid seventies. Hippies were all over the place with their communes and long hair and pot smoking. Maybe all our neighbors were hippies too. I know we hung out with at least one neighbor family. There are pictures of us kids dramatically eating popsicles. Perhaps they all thought we were innovative and came over to smoke dad’s awesome weed. Then again, this was the rural midwest. I imagine there were quite a few straight out farmers around who did not, as we did, treat the agricultural life as an act of assisted chicken suicide, but rather owned farms in order to cultivate food. Did they judge us? I can’t imagine they didn’t. Judging one’s neighbors is part of the American way. So when we tied the sheep to a stake in the yard to be dismembered by wildlife in the night, did brows furrow?

I can only speculate. I was very small, and those neighbors are most likely gone by now. Or maybe they’re still there, but it’s not worth the research. What I can confirm is that my brother and I thought everything was magical and dad was a genius. There were animals to harass, all sorts of room to wander, and we could scream as loud as we wanted, because no one would hear us, even our parents when one of us was bleeding to death. We had a barn with a hayloft. Really a barn seems a luxury for us, considering how little it was used aside from fostering the great rabbit army. But it came with the deal, so we had one. I used the hayloft window one day to scare the hell out of my mother as I stood up there claiming I could fly. I was never able to prove it, because my father snuck up behind me, grabbed me by the waist, and forced me to descend in the conventional way.

The barn where I tried to fly. My mother informs me that we bought the farm from a man who was very unwell. The buildings were all crumbling, and this man had forgotten to feed the sheep, so this barn was full of their skeletons. One day, our dog Nana came running up with a skeleton in her mouth. Inside the skeleton rattled a little fetal skeleton.

When we acquired seven baby cows, my brother and I got to name them. When my parents had one butchered and served it for dinner, we found it hilarious to say, “pass the Fred.” We’d play make believe with the rabbits, stuffing their cages with sticks and leaves that we pretended were lettuce and carrots. My mother would find the poor things pinned down by branches after we’d abandoned our game and wandered away.

One afternoon I stumbled upon three dead bunnies hanging by their ears from one of our rare fences. I asked my father why he had killed them. He told me he planned to cut them up so we could eat them. I used this opportunity to test a theory I’d been working on at the time. I simply did not believe that the heart was actually shaped like the cute little pointy symbol so often seen on greeting cards. It didn’t add up. So I convinced my father to let me watch him butcher a rabbit.

This wasn’t Fred. This was Joe. He dragged heavy things when he got bigger.

I stayed up what seemed like hours past my bedtime. The “M.A.S.H.” opening theme, our cue that it was bedtime, had long since played on the black and white television in the living room. Watching him skin the poor thing was interesting enough, but after he’d cracked the ribs and started pulling out organs, I pestered him incessantly, wondering “is that it?” until he finally produced a shapeless lump he announced was indeed the creature’s heart. I was surprised it was so small. I figured a heart, the symbol of love and life should be at least the size of say, a cheeseburger or a medium sized turtle. And this thing was just sort of a shapeless mound, not anything like the well known icon. I felt vindicated, and my discovery produced a flurry of questions. Is that really it? Why is it so small? Why do they call something heart shaped if it’s not really shaped like a heart? Why did they invent that shape if it doesn’t look anything like the real thing? Are we really going to eat this bunny? This went on briefly until my father announced that he’d let me stay up to see the damned thing, and now I’d seen it, so go to bed.

Early in their marriage, my mother accepted my father’s challenges like an obedient soldier. Raised Catholic, she was committed to marriage and determined to humor his schemes. She approached farming with a tentative resolve. Having spent summers on her grandparents’ farm as a child, she had much more experience. She baked her own bread and fed us fresh vegetables from her garden, fed the livestock and planted tulips and crocuses. But her time as a farm wife was a struggle.

Me with our dog Nana and a cat.

This is how I remember her back then: she ushers us frantically inside, and we watch from the upstairs bedroom window as she fires a rifle at a fleeing rabid skunk. She is a terrible shot. Puffs of dirt spray often several feet away from the creature as it zigzags off like a shamed drunken relative. I point to the spent shells on the bedroom floor and gasp, “Mommy! You’re shooting the wrong way!” The mechanics of firearms have never been a strength of mine.

There was a round red stain on the kitchen ceiling. She’d been making a strawberry pie. They often fought after my brother and I had gone to bed, but this time we had watched as she threw the entire pie tin straight up. Filling dripped on the table as dad stalked from the room. I don’t know what the fight was about. I rarely did. The red circle never came out. It remained an ominous decoration that nobody looked at when she was in the room.

Me, my brother, and my mom at the woodpile.

Here is how my mother remembers me back then: They once installed a new aluminum door on the house, possibly the one I stabilized during the typhoon, possibly its replacement, or maybe this door was unrelated. As soon as it was in its frame, I plastered the thing with crayon. She was horrified and asked me why I had done it. I looked at her earnestly and said, “It was so plain.” Another time I peed in her coffee. She didn’t realize this until she had taken a sip. She tentatively asked, “Thadra….did you pee in my coffee?” I nodded the affirmative. When she asked me why, I just shrugged. I can’t confirm these claims. They are not in my sparse collection of farm memories. But mom’s a pretty straight shooter, so I’m inclined to believe her.

Our career as a farm family ended when my father decided for the first of many, many times to divorce her in his relentless pursuit of a life spent elsewhere. She refused to be left with two small children in the middle of nowhere on a useless pot farm, so she insisted he find us a place in town before he went on his way. My brother and I thought our new home was a palace. It was a white three bedroom house in a small town that offered thrilling new adventures. Dad didn’t leave this time. He settled in with us for the small town experiment. We didn’t stay there long, either.