Govinda's Vegetarian

The most spiritually conscious meal in Downtown Brooklyn.

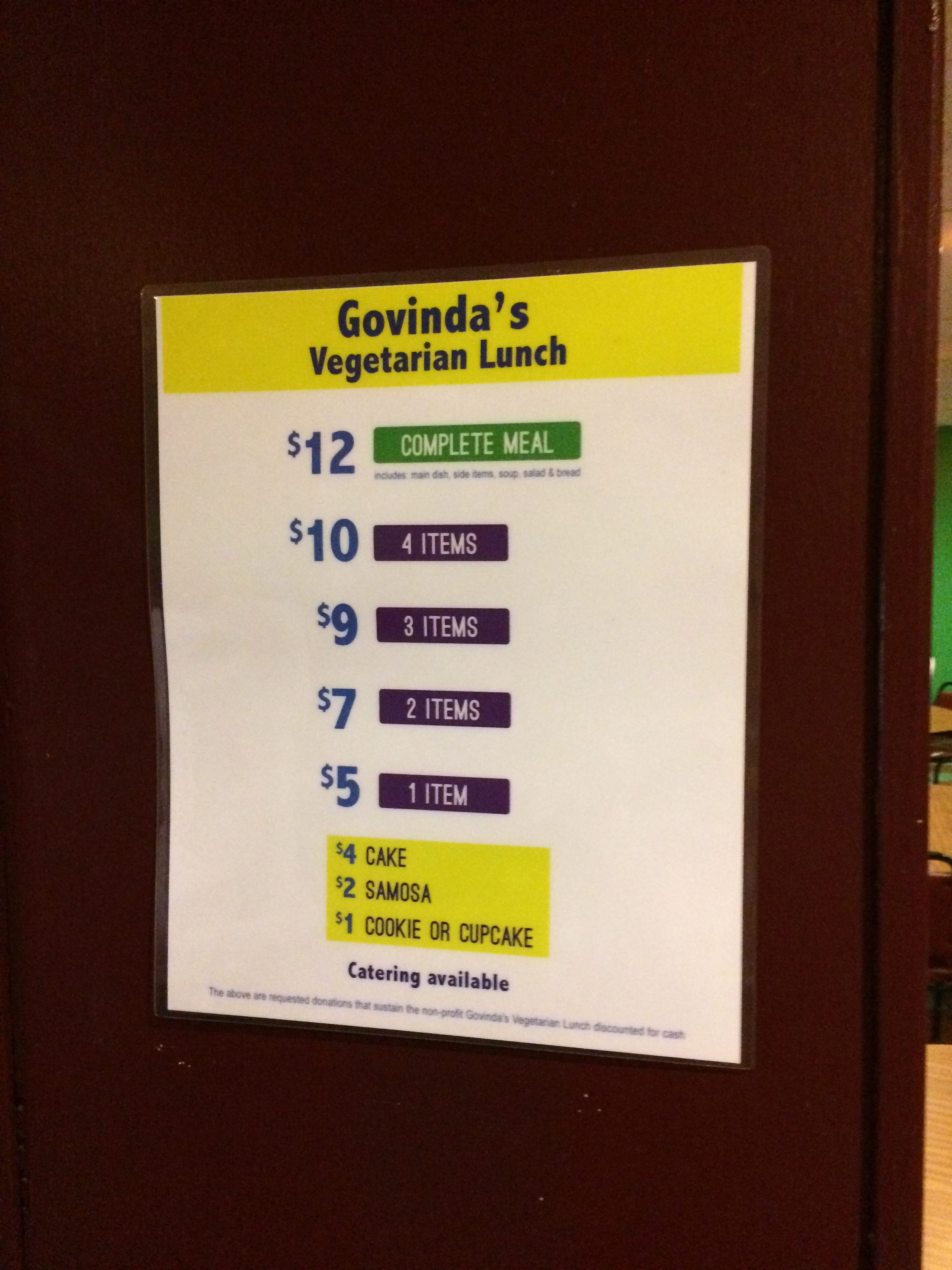

In Downtown Brooklyn, in an unappealing wedge of commercial real estate—banks and pharmacies and offices, ceaseless construction, the snarl of traffic along Flatbush Avenue, the gleaming curves of the Barclays Center in the distance—there is a Hare Krishna temple that serves a vegetarian lunch buffet, Monday through Friday, noon to 3:30. The food is good, but more importantly it’s pretty cheap: two items for $7, three for $9, four for $10, a “complete meal”—the entrée of the day, plus all the sides—for $12. My favorite is the eggplant parmesan, served every Thursday; I’m also partial to the breaded tofu with green sauce (Tuesday). The nut loaf (Wednesday) is a little strange, but there’s always something else to choose: channa masala, black-eyed peas, cauliflower, spinach, potatoes, rice, kale, quinoa, beet salad, samosas. The cheesecake is $4, and exquisite. The bread is free.

The buffet, called Govinda’s Vegetarian Lunch, takes place in a dining hall in the basement of the temple, located at 305 Schermerhorn Street. The hall is windowless, but the room is painted brightly, in green and pink and orange; on one wall is a mural of blue-skinned Krishna playing the flute for a trio of lusty milkmaids. Sitars and chants drone from speakers in the corner. Every lunchtime, the hall fills with a cross-section of Downtown Brooklyn—bankers, bureaucrats, construction workers—as well as a smattering of Hare Krishnas, with their saffron robes and shaved skulls. Sometimes there is a long line. The cuisine can be a little incongruous—Indian meets Italian—but nobody seems to mind.

Hare Krishna—or, more accurately, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness—came to the United States in 1965, when a man named Bahktivedanta Prabhubada secured free passage on a freighter from India to New York. He was sixty-nine years old and in poor health, and he brought with him little more than a suitcase and a crate of sacred texts. But his guru had tasked him with bringing Gaudiya Vaishnavism, a four-hundred-year-old Hindu tradition, to the West, and so he did. When he arrived, Prabhubada floated around the Lower East Side in his robes, attracting a coterie of aimless young people. (Remember, it was the sixties.) Eventually, they rented a storefront at 26 Second Avenue; it had previously housed a shop called Matchless Gifts, and the new tenants decided the name remained apropos. It was also the perfect location to attract hippies and dropouts, who, in the hypnotic ecstasies of Hare Krishna, found a different kind of altered state.

The main thing everyone knows about Hare Krishnas is that they chant. The nickname itself, in fact, comes from their sixteen-word mantra, reciting the names of God: Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. For believers, this is no mere incantation. There is something about this mantra, about the sonic vibrations it creates, that puts one’s soul in direct communication with God. Devotees are meant to say it a lot, everywhere, which is how Hare Krishnas came to be associated with chanting in airports and Tompkins Square Park—and how they came to be a reliable pop-culture punchline.

On a recent nut-loaf Wednesday, Satya Britton, one of the temple’s two head chefs, toiled away in the Govinda’s kitchen, chopping apples for a tart. She co-founded the restaurant ten years ago. Food is a central part of Krishna Consciousness, and there are dozens of Hare Krishna restaurants around the world: Toronto, London, New Delhi, Buenos Aires, Nairobi. Most of them are also called Govinda’s—Govinda, one of Krishna’s many names, means both “protector of cows” and “one who gives pleasure to the senses”—and they help fund their home temples. Like many devout Hindus, Hare Krishnas are strict vegetarians. “Krishna likes animals,” Britton told me. “He created everyone. He wanted everyone to be kind and compassionate. If you’re eating meat, you’re eating all the chemicals processed by the animal—the fear that’s in them.” Hare Krishnas also avoid eating garlic and onions, among other foods, since they are known to inflame the passions.

Hare Krishna is sometimes described as a cult, and the seventies and eighties brought innumerable headline-grabbing scandals: allegations of brainwashing, faux-charity scams, boarding-school sexual abuse, drug smuggling, even a couple of murders. Britton is sanguine about the whole thing. “We were a little nutty in the seventies,” she said. “The movement was young. They were fanatics. You know, ‘I found something that makes me happy, so I’m going to make you understand. You’re going to be happy!’ It’s mellowed out.” Contra their aggressive reputation, the Hare Krishnas don’t proselytize at Govinda’s. You could eat there every day and never learn a thing about Krishna Consciousness.

I ordered a “complete meal” and sat down with Britton, who has the luminous skin of a lifelong vegetarian and the harried air of a food-service employee. Now forty-seven, she has been a Hare Krishna since she was five; her mother converted after taking some cooking classes at a local temple in Baltimore. When Britton turned eight, they moved to a commune in rural Pennsylvania. “Some kids didn’t like it so much, but I loved it,” she said. “Country setting, beautiful farm. We played in the fields, we worked in the garden, we cooked fresh food. Every summer we canned tomatoes. We had orchards and made apple juice.”

In 1990, Britton and her mother left the commune for Downtown Brooklyn. The neighborhood was a very different place back then. “It took me a month to go outside,” she said. “You’d have to walk by drunk guys—they’d gone to the bathroom all over the place, on the sidewalk. People didn’t want to visit. Cars would get broken into. Everything was just parking lots.” Now, housing prices are astronomical, and condos and high-rises sprout from every corner.

It’s not clear how much longer Govinda’s will stick around, since, like everybody else in Brooklyn, the temple leadership is thinking about moving to Queens. Even as Downtown Brooklyn’s real-estate boom has priced much of the Hare Krishna congregation out of the neighborhood, it’s also made the temple property, which was built in 1930, extremely valuable: it’s reportedly on the market for $60 million. Not everyone is keen to move. “Our congregation is fighting,” said Britton, whose husband is the temple president. “Same thing that happens in every church: management wants to sell and the congregation wants to stay. Well, some of them want to sell. They understand that there’s a higher goal and purpose. We would make a facility that better suits our needs: bigger temple room, bigger restaurant, food hall. A little different.”

As Wednesday afternoon went on, I talked to a woman named Kristina Reintamm, who has been coming to the buffet for several years, ever since she started working next door, at Brooklyn Community Services. “Somebody pointed me in this direction and said, Just so you know, it’s a Hare Krishna temple, as long as you’re comfortable with that,” she said. “I did ask, Do you think people are going to try to recruit me?” Reintamm likes that Govinda’s is healthy and vegetarian, although she’s a little miffed that lassis cost four bucks. She was also eight and a half months pregnant. “That’s the other reason I’m honestly here all the time,” she said. “I can’t walk much farther than this place. I don’t even feel like eating this anymore, but it’s kind of my best bet.”

Francesco Vitelli, who works for a bank in the nearby MetroTech Center, comes to Govinda’s nearly every day. “I always threaten them with, if I get laid off, I’m gonna show up with an apron,” he said. “I don’t know how to replace my lunchtime ritual.” He mentioned DeKalb Market Hall, the artisanal-food court that recently opened around the corner, and a high-profile symbol of Downtown Brooklyn’s embourgeoisement. “I figured, Oh, that will change the game for me, and it didn’t. I see none of the comfort,” he said. “It’s a lot of typical, food-truck-guys-opened-a-store kind of thing. A Bushwick Vietnamese place and a Crown Heights Korean place, that kind of thing. Sure, it’s interesting and shiny-looking, but I walked through there, I looked, I enjoyed—and then I came back here.”

After leaving Govinda’s, I decided to check out DeKalb Market Hall for myself. I headed to the City Point building, just off Albee Square, and descended an escalator to the food court. There were stalls selling arepas, pierogis, jianbing, paella, doner kebab, gua bao. There was a Katz’s, a Wilma Jean, an Ample Hills. A craft-beer fridge waited to be stocked; red meats gleamed from butcher-shop cases. Someone painstakingly hand-painted a retro deli sign. It all looked, and smelled, amazing. But everything seemed a little pricey, and anyways I was still full.