Was Bernstein's 'Age Of Anxiety' Written for 2017?

The only constants are change and Leonard Bernstein.

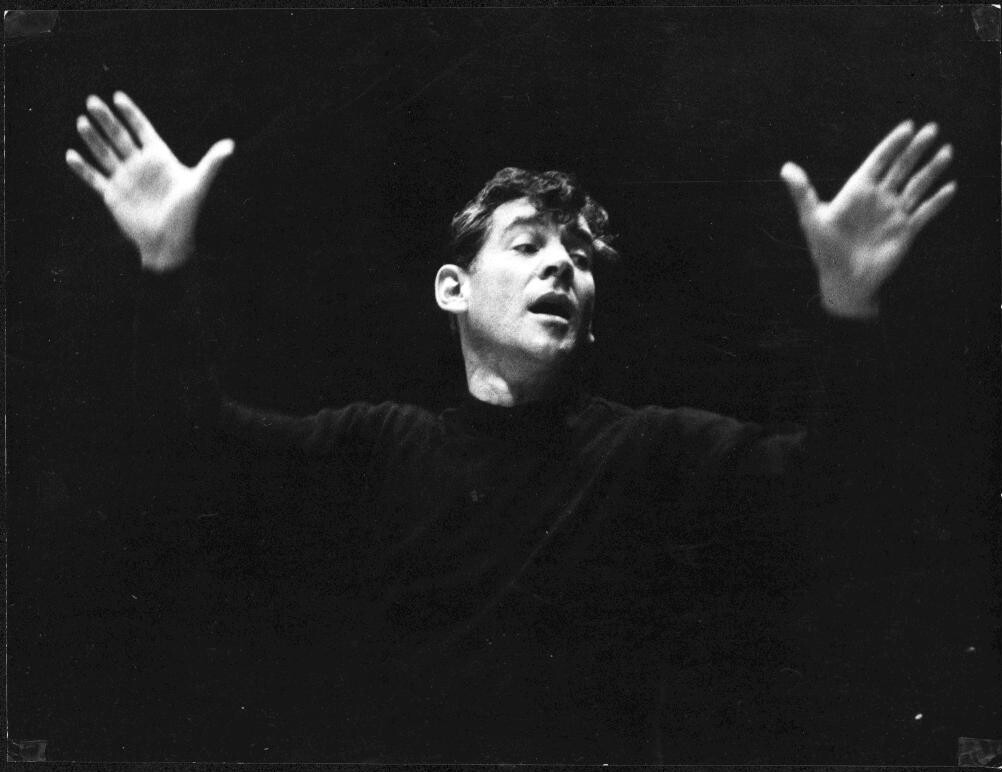

Image: Leonard Bernstein Collection via Library of Congress

How are you feeling? How are you doing? It has been an interminable few weeks, months, year, etc. A regular stand-up joke I like to tell is saying this year is better than last, but I am barely certain that’s true anymore (it’s not, probably). I spent a few weeks (see also: 10 days) “off the grid,” and while I will never preach the idea of deleting one’s account as a catch-all salve, it is a good thing to do every now and then. Like when you remember you’re supposed to drink water or have a glass of milk before bed. Consider it, is what I’m saying.

It can feel useless writing about classical music at times. On one hand, I worry about sounding elitist, straining to recall anecdotes from my obscure musical background. It’s a niche and privileged interest, one that bears little weight on modern conversations. On the other hand, I think of my brother, a teacher in the middle of the country, whose coworker plays arabesques for her students while they read books of their choice. It’s all relative, is what I’m saying.

70 years ago, poet W. H. Auden published a long-form poem called The Age Of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue about four strangers meeting in a bar in New York City, discussing the way society has changed during the war (“baroque eclogue,” by the way, means this is a pastoral poem written entirely out of dialogue). I confess that I haven’t read the poem, but the phrase “age of anxiety” has certainly seeped into the way we, broadly, as a people, talk about the times, be it the 1940s or the 1960s or the nows. One of posthumous friend of the column Leonard Bernstein’s friends mailed him a copy of the poem, and wrote the following note in the margins:

Why don’t you try a tone poem of ‘Anxiety’? The four themes—their inter-relationship, pairing-off drama—etc. Might make a good thing. And you could do it!

His friend wrote him again, four days later, with a more long-winded urging for Bernstein to adapt Anxiety into a piece of music—a symphony, or maybe a ballet. For what it’s worth, if you are my friend, never contact me twice in four days. The idea, however, stuck. No doubt Bernstein was moved by the poem––which went on to win a Pulitzer the following year—though Auden somewhat disowned the composer’s piece, saying: “It really has nothing to do with me. Any connections with my book are rather distant.” Hahahaha, damn, though I think all of us could learn from the phrase, “it really has nothing to do with me.”

In many ways, though, Bernstein was the perfect person to adapt the poem: he, too, traveled extensively, composed across genres, explored his own sexuality. He, too, was in transit, as the poem suggests all of us are. The piece is written for an orchestra and a solo pianist; at its 1949 premiere with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Bernstein himself played the piano. This week I’m using a Bernstein-conducted recording from the New York Philharmonic, featuring Philippe Entremont on piano. (Speaking of said New York Philharmonic, if you’re lucky enough to live in the Biggest Of Apples, you might want to check out their Bernstein festival, ongoing for the next two weeks.)

Unlike the four movement symphonies of the previous century, The Age Of Anxiety—which was, for the record, Bernstein’s second symphony—has six movements. It begins with The Prologue, a mere two and a half minute piece that is almost exclusively woodwinds. This is setting the stage, so to speak, of both the poem and the symphony to follow. Not unlike the poem, which depicts the four strangers settling into a bar, this is a purely conversational piece of music, as if the orchestra itself is settling into the bar. It’s uncertain, tipsy, melancholic. It’s a call for a last round, long after you should have been cut off.

Immediately following with a solo piano is the next movement, The Seven Ages, which breaks down the “life of man.” What about the life of Woman? My two cents. This section is built into seven variations, each one subsequently building on the one that came before it. It’s tumultuous and magical and overwhelming, in the way life often is. Though I’ve not seen the ballet and can’t visualize fully what each section may denote, there’s a part at the 1:41 mark that feels so inherently childish and ethereal that it feels right out of a fairy tale. I’m also quite partial to the variation at 2:40—languid and erotic. If this is not adolescence, I don’t know what is. I mean, obviously not my adolescence, because I was waist-deep in this world, but hopefully it rings true to someone way hotter. This is the longest piece in the symphony, and rightfully so, I think, because life is long and complicated and strange and upbeat and confusing. It’s utterly thrilling though, and if The Prologue didn’t immediately hook you, this certainly ought to.

If you didn’t have enough of seven variation-long movements, then you’re in luck, because what follows immediately is The Seven Stages, the part of the poem and symphony in which the four protagonists all, um, go on a vision quest and become one organism? Look, I don’t know, the 1940s were insane. Let’s just look at this one musically, for sake of not delving into fictional characters’ highs once again. It starts like a death march, almost frightening and methodical. Anyone else watching “Mindhunter”? Never mind. By the halfway point in the piece, the combination of the swirling parts—the triumphant brass, the dizzying piano and xylophone—it’s almost like a cityscape gone awry. This is like La La Land on crack.

The Dirge, which follows, marks the second half of the symphony, which takes on a darker tone overall. It’s manic and confusing—kind… of… like… women? 🙂 In this movement, the characters take a cab ride back to the woman’s apartment for a nightcap. Just kidding, they’re only in the cab during this section. What function does the solo piano serve in this piece? I’ve written about piano concertos before, but that’s not what this is: this is orchestra and piano. They have equal measure and equal power. The piano is the protagonist, not the character actor. In its final minute and a half, The Dirge gets percussive and frightening. Something has been lost; it’s a dirge, after all.

You might mistake the opening of The Masque as a seemingly normal jazz piece you’d hear at a nightclub. The hi-hat, the piano, the triangle! What fun this one is, at least on its onset. There’s even woodblock, thankfully. This movement feels almost too traditional, too good to be true. It’s as if the night, now unhinged from the bar, grows wild and free to become something bigger and brighter than itself. In my times away from the symphony, I find myself humming the little melody at the 1:40 mark. This is an absolutely iconic piece for any xylophonist, and one I would have killed to play during my musician days. It’s just so jubilant! Things, however, are starting to wind down after time and when the orchestra falls away, the piano, our protagonist, soldiers on through the edge of night.

And at long last, through the drunkest and coldest of nights, we reach The Epilogue all together. This is the great leaving, the grand departure, the elves taking the boat to the Grey Gardens for reasons I don’t fully understand. Our four strangers have had their magical and strange night together, and now they go their separate ways. The piano lingers throughout the finale, like a quiet set of footsteps approaching the sunrise. The Age Of Anxiety feels prescient and strange and unnerving now as it did back then, perhaps because the anxiety hasn’t ended, only mutated beyond something we know. There’s a comfort, however, especially in the final two minutes—right at the 6:16 mark of The Epilogue. A togetherness, maybe, in a piece we can share, if only for the night.