How To Cry At Bruckner's Fourth

First, you have to go see it live.

It would be vaguely interesting if I could use this column to convince you to see classical music live just once this year. Would you consider it, honestly? Even for a few minutes before you decide to buy a new sweater or a decorative candle or something like that? Which is not to say that seeing classical music live is more important than those other things; it’s just a different experience altogether.

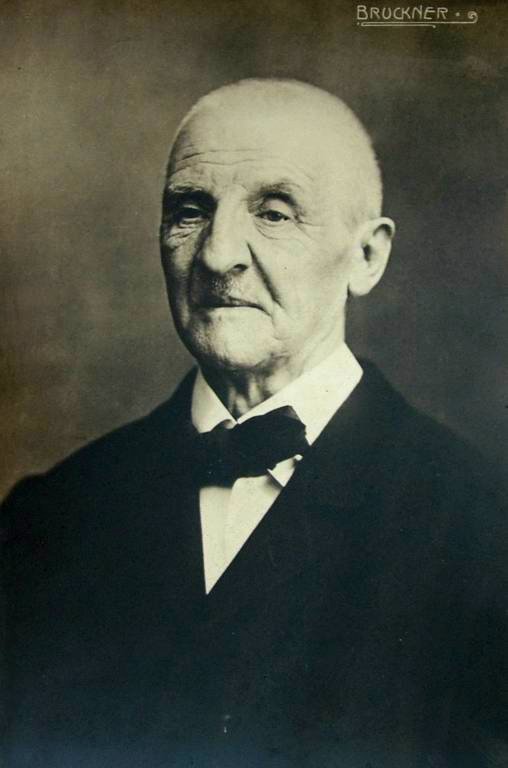

I am feeling very sentimental about seeing live music if especially because I, personally, me, yes, did just see the first concert in my subscription this year, and yes, in fact, I did tear up during Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony aka Romantic (the Chicago Symphony Orchestra this time! A 1997 recording) which is both embarrassing and a brag. It’s not that I get Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony more than you would. I didn’t anticipate crying. It is just such a full piece of music, and there are few experiences on par with listening to a piece of classical music when you have nothing else you’re supposed to be doing. I encourage people to work or write or read or run to classical music—that’s fine! It’s nice! But when you are working to listen, your mind will wander on its own, conjure images and associations, as mine did for the first time in a long time listening to this particular symphony.

If you recall correctly, the last time I wrote about Bruckner I compared him to Brahms, which many have written to tell me is simply not correct. First of all, I think that’s probably true. Second of all, please calm down. Without comparisons to other 19th century composers, allow me to say this: Bruckner’s tendency towards spacious, elongated symphonies is something I used to balk at that I now feel very warmly towards. Listening to Bruckner is a little bit like hearing a long story from your friend who has a tendency to ramble. My brother, for instance, does this: he speeds up the telling of every story in a breathless and excited way, and then the next thing I know, it’s been twelve minutes. Same thing here. In fact, the version of the Fourth Symphony I saw last week ran at [extremely long and deep breath] 69 minutes. (Nice.) It’s a journey, but one that is well worth taking.

It’s possible—though a lot less so than last week—you recognize the main theme from the Fourth Symphony. It’s okay if you don’t. This one is a lot less famous, certainly, than William Tell Overture, but no less memorable once it’s stuck in your head. The Fourth Symphony was composed and revised between 1871 and 1888, the height of the Romantic period, hence its subtitle. It’s not strictly speaking a piece of romantic work—lowercase ‘r’—because unlike Brahms, it has nothing to do with a woman. It’s really just named for the times (a sign of the times?). It is also a programmatic piece of music, meant to depict a medieval city complete with a surrounding forest full of life and knights and hunts and townspeople. You can feel the immensity in the first movement, the Bewegt, nicht zu schnell (with motion but not too fast). He’s not building an emotion so much as he’s building a world. It’s easy to project yourself into Bruckner because he’s inviting you to. “Here’s my town, here’s how it feels, how it sounds, come on in and explore it.”

And if we’re talking spacious, then of course we should talk about the second movement, Andante, quasi allegretto, which is the most woodlands-esque movement within the piece. This is basically the most high art version of the Game Of Thrones opening credits. Listen for the cellos at the 3:13 mark. Isn’t it all a trek through shady brush and wet grass? It’s wandering but not wistful, contemplative without being entrenched in nostalgia. It’s meant to invoke birds which, yes, when you use a bunch of little melodies on the flute, it’s pretty easy to think, “hey, are these birds?” Even though birds are the all-time worst animal, I have to admit that Bruckner can make them seem artful and rightly in their place. That said, when I saw the Fourth Symphony live, I never once thought of birds.

The Scherzo is the quickest movement by far, at a brusque nine-and-a-half minutes. Bruckner meant for it to symbolize a hunt (RIP BIRDS). Remember hunts? Very weird as a social activity but I guess men will do literally anything together other than empathize. As triumphant and rollicking as this movement often is, I love how textured and fully formed it is. It’s more than a dance, as scherzos often have the reputation for being. Every time the fanfare returns––as brassy and showy as it is and dare I say, of course, masculine—I can’t help but want to cheer. It’s all-inclusive in its joy, wanting you to participate rather than sit on the sidelines.

Last but not least is the breathtaking finale, Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (same as the first movement). Its opening three minutes carry over the drama and the sheer volume from the Scherzo, and Bruckner really draws you forward out of your chair with the force of the brass. But what this movement does that was so wondrous to me when I saw it live was play with volume and intensity in conversation. Once the movement settles down, it ebbs and flows between darker, slower melodies and the violent fanfare from before. But it doesn’t come off as disjointed or scattershot. It’s emotionally complex without being sonically so. Wouldn’t you be tempted to cry, even a little, if you felt the range of setting and feeling that Bruckner tries to establish in these 69 (hell yes) minutes? I left the symphony center with chills, recalling not necessarily the melodies I had just heard, but what I had felt listening to them. It was like coming up for air, jacket pulled snug over my sweater, making my way back home.

There is a corresponding playlist for all pieces discussed in this column here.