Banker Street, Brooklyn

They took you to church.

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

Maybe every metropolis can do this, maybe, as with dog owners who believe their dog to be the most-beloved and special among all dogs, this is just the New Yorker’s delusion of exceptionalism: but, does any other city do human irruptions like this? An aromatherapist once told me it’s tectonic. She said this matter of factly and I liked the idea of using the word as a catch-all explanation for your phenomenon of choice. A term up there, in this sense, with “hormonal.” Applied to New York though, “tectonic” was especially appealing. I liked the idea that the crackle on the streets on a sunny but crisp Saturday in late October had some chthonic source, one very vaguely scientific, but mostly mystical. I liked the idea that psychogeography could have a fount, invisible but earthy. I liked the idea that it wasn’t all just caffeine and collective myth-making.

It was golden hour, and the cafe that was also a radio station in an empty shipping container in a formerly empty lot—because yes, this was indeed north Brooklyn—had become a bit of a scene. Everyone was wearing sunglasses, which was justifiable—the light was low and bright and horizontal—but that funny thing was happening when you can tell that people are looking at each other even as you can’t actually see their eyes, that covert scoping that should be undetectable and yet is somehow obvious. Maybe it’s revealed by the way a person holds their head, some minute physical adjustment there. Or perhaps it’s inexplicable, a sixth sense. By which I mean maybe it’s just tectonic. Human tectonics.

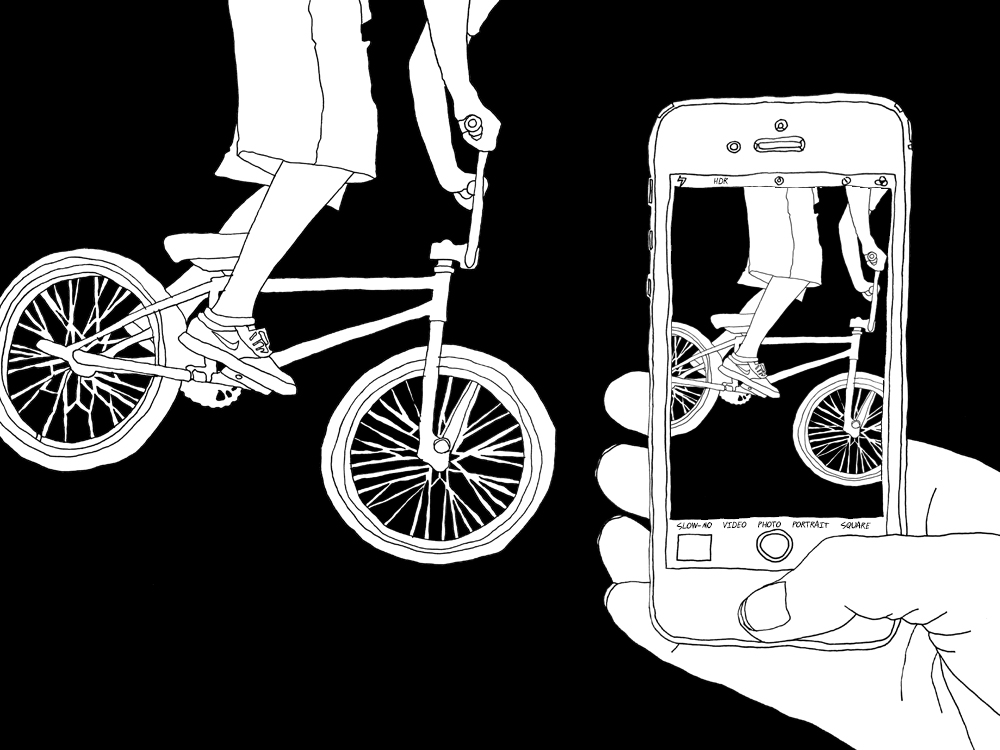

It was a scene, but then here came the irruption to eclipse the scene. Teenagers on bikes, maybe fifty or sixty, all African-American, all boys. A kind of rowdy battalion, dizzying and vitalizing. Where had they come from? And why here? Was it a shoot? I looked for cameras but the only recording devices were iPhones held down low to catch friends’ wheelies and other stunts whose names I don’t know. Cars honked huffily, trying to push their way through, and this sent a fresh wave of unruly, boyish noise through them, a sound ecstatic and derisive. We were all looking now, so we all saw you—a tall white man with villainously black hair stalking through this spectacle. Like meerkats, we, denizens of the cafe were instantly poised: amused, yet slightly tensed for confrontation, alert to a moral imperative to intervene as you said something peevish-sounding to the kids.

“He’s pissed that they exist,” I suggested, to no-one in particular. “On his street. That he owns.” “Just a mean old man,” said an African-American guy in sky blue overalls. “Oh is he going to church?” laughed a young white woman, following your stroppy progress into the San Damiano Mission, from where the monks, in their gray cassocks, often emerged to stroll and drink coffee and mingle with the young people in sunglasses. There’d been something mocking in her question, the implication of hypocritical self-righteousness on your behalf. Love thy neighbor and so on. Except when they’re in your way and being loud on bikes. I thought of the phrase “take him to church,” a phrase I love, and how much more I loved it as I watched it enacted: these kids, taking you to church by frustrating your progress to the literal church.

Your sour moment—mean-spiritedness at best, outright racism at worst—had sent a small solidarity into bloom. What was the ethical utility of this, a common enemy. Was it good, if we were all just bonded by you, an old white man being bad to some black boys? Did it absolve you, or implicate us? It’s not the same, but I thought of some lines in Zadie Smith’s Swing Time. The narrator’s mother, striving towards middle class righteousness, is in “a competition of caring” with the other, less bothered mothers of little girls. From the vantage of adulthood the narrator looks back on this and wonders, “is it some kind of a trade-off? Do others have to lose so we can win?” Did my delight in this crowd—our delight, because we were a we now, thanks to you—need boosting by antipathy for the mean old baddie that was you?