We'll Have The Fried Rice

The craving that dares not speak its name.

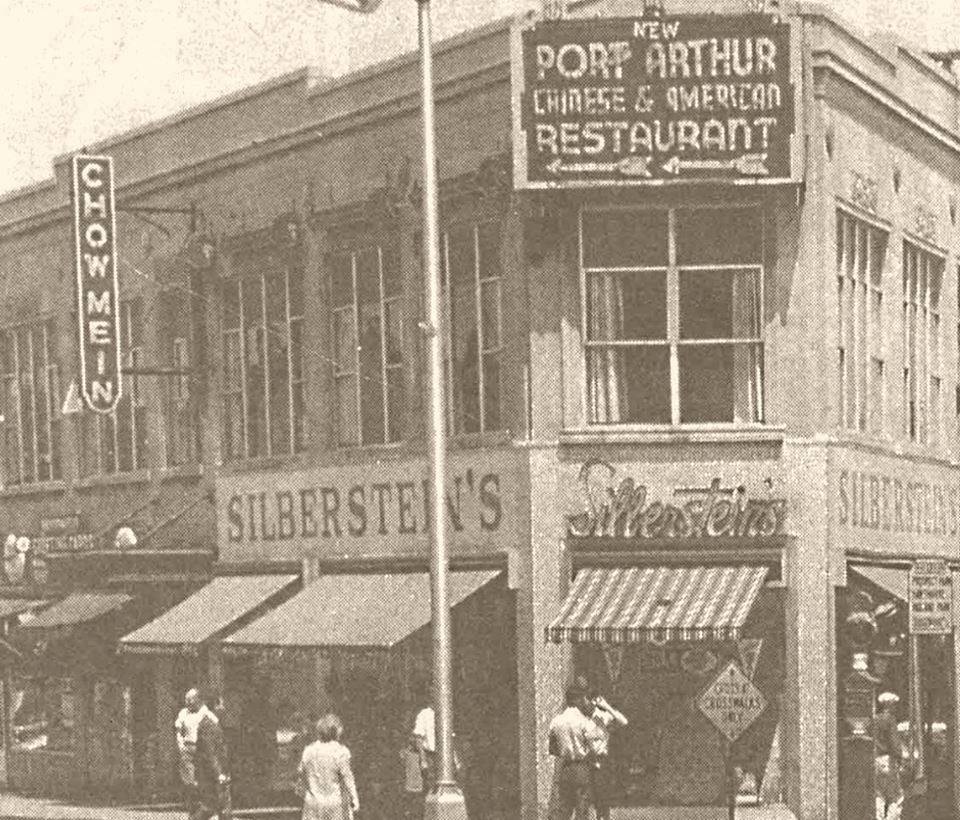

Image: I grew up in Paterson, NJ via Facebook

I grew up kosher till my father died. Religious I wouldn’t call him. Faithful, I would say. Faithful as in filled with faith, as sailing ships are sped forth by the swell of force those on the shore can’t see. Faithful in the sense of true, as an arrow that dips and pitches in its course is true, or true enough, within the wind-channel that slams it to its target.

Lumpen immigrants—Carpathian farmers, rough-edged, more or less unlettered—my father’s people liked God, liked God a lot, if in a casual way. To Him (God was a him then) they attributed all good things. Lapses, they looked the other way. They got tired, and so why not God? Who hasn’t felt her head nod on the job and, hoping no one noticed, jolted back to duty?

Buckwheat blight, goose-pen fence-rot: bad. Worse: stillbirth, typhus, dropsy. Worse still: Cossack raids. Beyond thought: that which was beyond thought. Cousins showed up in Red Cross transports at the docks, sink-eyed, with numbered arms. In terms of God—that, well, nobody could explain.

Still, otherwise they cut Him slack. And felt it their due to receive kickback in kind.

Kashrut—no pig products or shellfish, no dairy with the meat, that five-millennia-plus diet trend—they took as of deific device, wise and right.

But God had never tried the spareribs at Port Arthur Chinese Restaurant. Did God have a mouth? On this point my father was unclear. “God spoke to Abraham, to Moses. But maybe not quite like we’re talking here.”

My mother went to school at night. We ate most dinners by ourselves. He could cook just one dish: spaghetti with Ragu sauce from a jar and substantial scoop of sour cream: then and now, a holy Eucharist to me. Tuesdays and Thursdays we went out. The Port Arthur was up a flight of stairs with chipped maroon and yellow paint.The teacups had a pleasing heft. They played the Top 40 station he tolerated only there.

At any rate, God had ears. Or, evidently. Hence, I guess, the system—not stated aloud, per se, but well-modeled to me—by which it was kosher to order “the Fried Rice” as long as you refrained from pronouncing in full its menu name.

If the waiter supplied the missing term—“One order, Pork Fried Rice”—you had to take it back.

“Oh no no no. Oh no no. My mistake.”

Not for the waiter’s sake but God’s, obviously.

Same with “the Toast”: Shrimp Toast. Or: “This appetizer here, the Number 17.” Above all, the Port Arthur’s mockup, stateside, of “The Cantonese”: burlesque peeks of scarlet crustacean bobbing in a moody garlic-egg white-scallion sea—even for my father, raised so poor each dollar made him shake, a justifiably bank-breaking spree.

You could try “The Coldcuts” at an Italian wedding if you kept chatting about other things—gaze hazy, vague—while you forked soppressata, coppacola, mortadella, head-cheese into heaping piles on your plate.

As a guest in gentile homes you ate what had been served you. “The Applesauce and Chops” sizzled to succulence. It was common decency. “The Spinach Salad,” trawling the bottom for the smoky “Bits.” It was just polite. Anything billed as “Hawaiian.” Underneath the pineapple—well, let some things be mysteries. My dad could remember when it wasn’t yet a state.

Did you know that baloney, fried, curls on its perimeter, then puffs in the middle, forming the shape of what was then called a “Mexican hat”? Rainy afternoons at Joanne’s down the street, we tore through Oscar Meyer, packs and packs. My father, told later? Hummed the first lines of “La Cucaracha” and went back to grading papers or calling his best friend Sam up on the phone to joke.

We had two sets of dishes, to separate foodstuffs forbidden to meet. Different cupboards. A double sink. If a milchig knife touched fleisch you had to run outside and plunge it hard into the yard to be cleansed by the earth, then leave it for a week. You’d never let something traif pass your doorposts. Thus: awkward dawdling on the step—eyeing the outdoor trash cans—till the kindly neighbor, waving, turned the corner, leaving the “Casserole” of God-knows-what in your hand. God did, too—know, that is—if only in your kitchen and those of your fellow Jews.

At the latter, offered a YooHoo and hotdog in the selfsame meal, you were required to make an ostentatious deal of it: “Um, Mrs. Migdahl? I can’t—my parents—.” Or: “Ralph, medium-rare—but you can leave that cheese off of mine.” Not to be hypocritical—everyone knew that at the Old Barn Milk Bar we got Chicken in a Basket with big Rootbeer Floats. Rather, it was simply to have said so before God, tactfully removed from the Port Arthur, St. Mary’s basement event hall, and tract-houses near-identical to ours apart from sweet framed First Communion snapshots and crosses above the beds—yet omnipresent at the Migdahls’ barbecues, hearkening for hints of sin between radio-squawked Mets scores.

My father’s people were hardly Talmudic scholars. They spoke what they called “Jewish,” which is all “Yiddish” means: the idiom of kitchen, shop, the tragicomic ethno-secular divine. You died in Hebrew, but you lived in Yiddish. If my father knew much more of the sublime archaic tongue than the rote shapes of prayers—there’s no one left alive to ask—I’d be surprised.

Still, there was something classically Judaic in this loophole logic. And it’s been argued that the Yahweh of Judaic law is not, as thought, a God of Vengeance but of mercy. My father wasn’t unaware of the bases of kashrut—respect for animals, health, restraint in a wilderness otherwise without bounds—and, if asked, would have agreed. But his God was okay with a little bending of the rules as long as He was not explicitly involved. He’d let it slide.

The sacramental “Soup”: wonton. The low-rent rapture of plunging the Pu-Pu stick into Burning-Bush sterno fire. My father died at not-quite-38, a family disease. But his life, brief as it was, abounded with such blessings. Thank goodness.

Thank God?

Depends on whose.