The Teacher Dichotomy

Why can they only be Good or Bad?

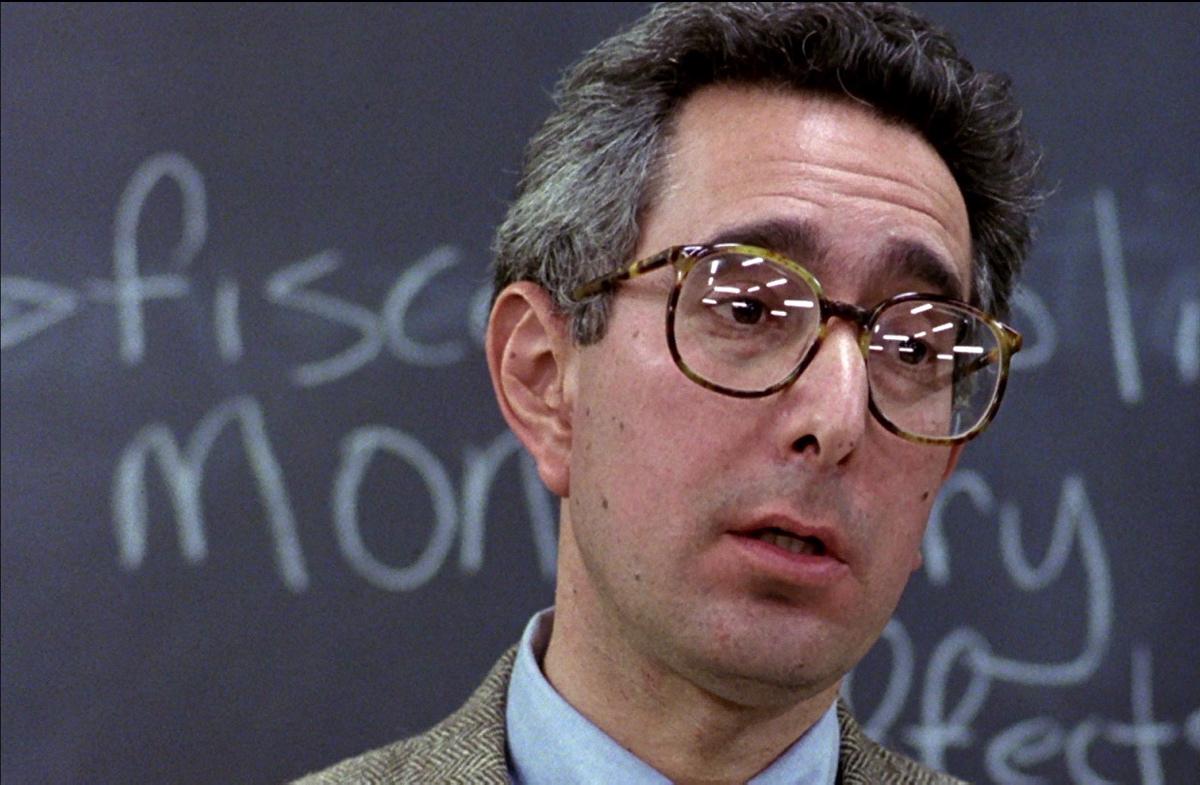

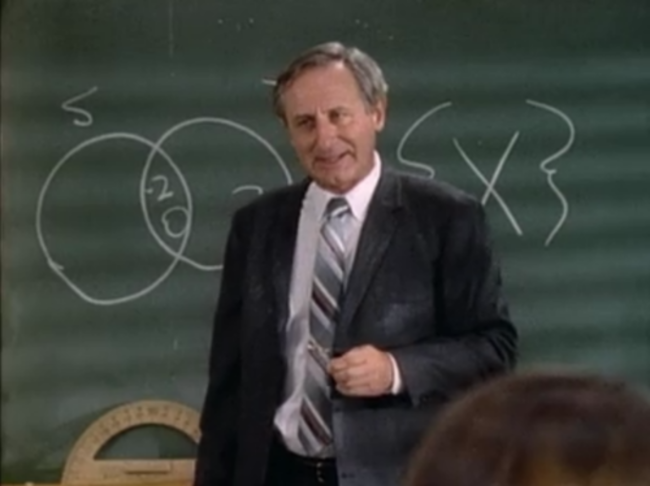

Ben Stein as The Economics Teacher in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

The nation’s kids scrutinize all the nation’s teachers every school day. All those kids are growing, and their minds are developing, and they’re prone to note the oddities of their teachers’ personalities, sartorial choices, and pretty much everything else. So you’d think that when those kids grow up, become writers, and depict teachers on TV and in movies, the detail they absorbed back then would get incorporated. But it rarely does. Why? I’d say, simple as it sounds, it’s because kids are emotionally vulnerable and the strongest resonances of their teachers—really good or really bad—stick with them. Kids are kept in the thrall of teachers every school day. All that rigorous character analysis of their teachers they mentally conduct while staring straight ahead, off to the side, or at that hard gum stuck to the side of the desk, is bound to fade in favor of a few emotionally resonant moments.

Because of this emotional imprinting, we see a lot of caricatures—strict binaries even—of very good and very bad teachers. The bad ones are legion in TV and movies. Take Ben Stein as an Economics teacher in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, droning on about supply-side economics and repeatedly asking in that immortal monotone: “Anyone, anyone?” The boredom gripping the room is well beyond existential, seeming to provoke even paralysis. The students, clearly in anguish, are staring straight ahead, while one student is even sleeping soundly, a small puddle of drool gathering next to his head on the desk. What makes the Economics teacher a bad teacher is obvious. He combines many of the worst bad teacher traits—bland, cold, uncaring—with an affectless affect. The aridity of his instruction is palpable, almost sublime in its ineffectiveness. Oscar Wilde thought it was absurd to consider people good or bad because, in reality, they were really either charming or tedious. Most kids, I think, feel the same way about teachers.

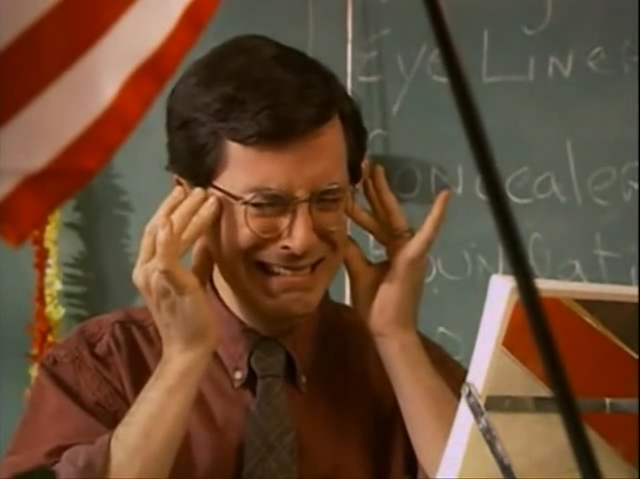

Stephen Colbert as Chuck Noblet on “Strangers With Candy.”

Another classic bad teacher is Stephen Colbert’s character Chuck Noblet, from the Comedy Central series, “Strangers with Candy.” But Chuck Noblet is not just a bad teacher in the bland manner of the Economics teacher from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. No, he’s in another perennial category of bad teacher: the unbelievably bad teacher. He’s comically absurd in his improvised instruction and deranged in his comments to students and others. The character is a really funny, over-the-top display, which of course doesn’t admit much verisimilitude, except that it does. Probably a good number of us never had a teacher quite as bad as Chuck Noblet, but the emotional resonance we feel from being embarrassed or wildly confused by an obviously incompetent teacher remains. While watching, we can let loose in laughter long after the fact of our experience, knowing the Noblets of our lives are deep in the past and it’s safe to laugh at them now without getting yelled at, as it should have always been.

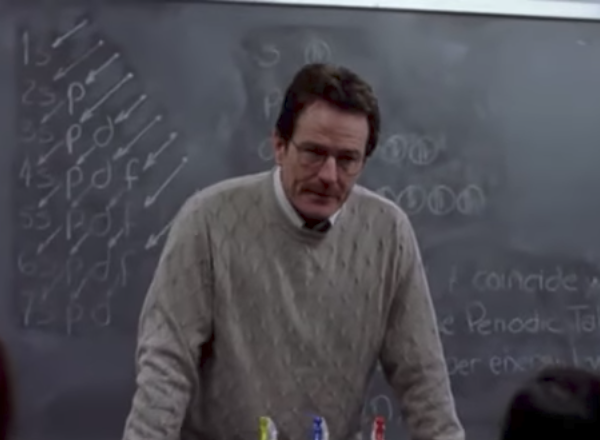

Bryan Cranston as Walter White from “Breaking Bad.”

But perhaps the darkest expression of the bad teacher on TV is Walter White in “Breaking Bad.” He’s indifferent in the classroom and goes about his day listlessly, since he was once a brilliant chemist hurtling toward great wealth, and now he’s a failure. Almost from the outset, he’s one of the darkest, most complex characters in television history. The most salient symptom of his failure is that he’s a teacher—rarely if ever does he consider teaching to be more important than a life propelled by ego, pride, acquisitiveness, or ambition. There are many moments where he seems on the verge of an epiphany, and many more where it seems he can’t endure his inexorable trajectory anymore. Notwithstanding his cancer diagnosis and maybe his oblique concern for his family, Walter White’s humiliation stems primarily from his being a teacher, a scarlet letter “A” of mediocrity to many, and that propels him into amoral fury. What remains simple throughout is the equation: teacher = failure.

Edna Krabappel from “The Simpsons”

Sometimes failure can lead to a second career in teaching that is complicated but still meaningful. One example is Roland Pryzbylewski from the HBO series “The Wire.” In season four, the former police officer is teaching middle school in West Baltimore. After some struggle and more persistence, he finally forges connections with many of the students and yields pretty good results. He’s a quiet, complicated success, common among the actual teaching multitudes. Another rare example of the complicated good teacher is Edna Krabappel from “The Simpsons.” No one would accuse Mrs. Krabappel of being a model educator. But, to her credit, she runs a seemingly well-organized classroom, brooks no nonsense, and the students are usually occupied with an appropriate assignment for their grade level. In her own world-weary way, she lends structure and discipline to her students’ lives.

Edward James Olmos as Jaime Escalante in Stand and Deliver.

But enough of complication. Almost all positive depictions of teachers on TV and in movies go improbably far beyond the merely good. They’re most often heroic types possessed of superhuman patience, fortitude, and dedication. Unfortunately, there are too few representations of women and people of color in these heroic teacher depictions, although Ms. Norbury from Mean Girls, Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid, and Miss Bliss from “Saved by the Bell” are notable exceptions. Another great exception—and based on a true story—is Melvin B. Tolson, a professor at Wiley College, played by Denzel Washington in The Great Debaters. In the film, Tolson, facing considerable resistance, cultivates a debate team that starts out almost from scratch and eventually is in the position to face off against Harvard.

Jaime Escalante in Stand and Deliver is also classic heroic teacher depiction and, like Tolson, an exception to the white, male depiction norm. Stand and Deliver is based on the true story of a Los Angeles public school math teacher, but that doesn’t make a teacher like Escalante any less incredible. He walks in and almost immediately establishes a rapport with his tough students, challenges them to be great, confronts socioeconomic disparity, is effortlessly creative, and even suffers a heart attack in the process. Mr. Escalante is the epitome of the demanding, inspirational teacher type. And sure, what he does in the classroom is sometimes possible in real life. The difference is, it can take many years of experience to develop the skill to pedagogically dazzle in the Olympian way he does, and still every day won’t necessarily be a triumph of the teaching spirit. Raise your hand if you remember a teacher always this perfect. Anyone, anyone?

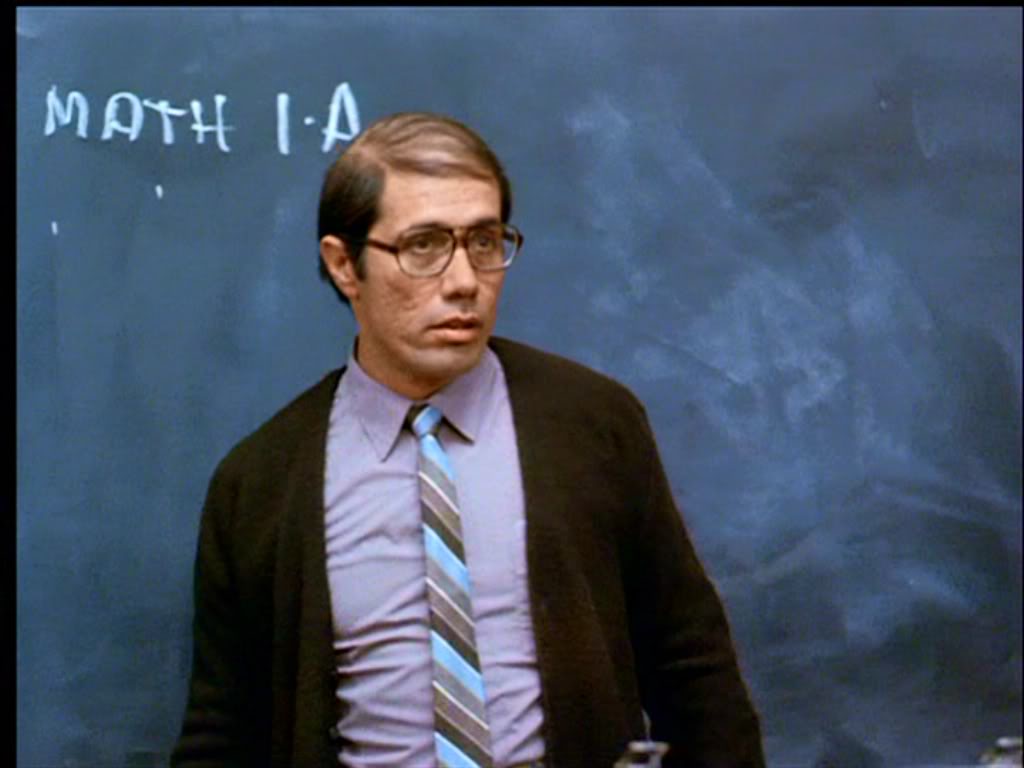

Steven Gilborn as Mr. Collins in “The Wonder Years.”

The same goes for Mr. Collins—whom we see notably through a single student’s perspective—in season three of “The Wonder Years.” He challenges Fred Savage’s character, Kevin Arnold, to succeed in math by quietly, firmly goading him on. When Kevin buckles down for review sessions with him to try for an “A” on the mid-term exam, Mr. Collins unexpectedly has to cancel a couple of sessions. Kevin resents this and fails the test on purpose. Soon after, he finds Mr. Collins has died. Yet, apparently, in his final hours, Mr. Collins had reserved another mid-term exam for Kevin to retake, knowing he’d rise to the occasion. Mr. Collins is a clear example of the inspirational teacher type who, with perfect skill, demands excellence, but the narrative of the episode is too easy to credibly depict the difficulty over which he helps Kevin to triumph.

Robin Williams as John Keating in Dead Poets Society

Alternatively, there’s John Keating, the boldly Romantic English teacher, played by Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society. A heroic type turning his students’ hearts toward a different purpose, Mr. Keating isn’t so interested in academic results as he is in teaching students to trust themselves, think independently, and pursue what they love. He’s a master teacher too, but the right brain complement to Mr. Escalante’s and Mr. Collins’s left brain. Slinging verse and wit, he urges his students to sound their Whitmanian yawps against the strictures of their staid upbringings. His is a teacher type who seems to believe that education begins and ends in undermining school, or, more broadly, that true learning exposes the fallibility of institutions and their protocols. And maybe he’s right. Many of us sympathize with that sentiment, maybe even to the point of standing up on our desks, given the right circumstances, to proclaim “O, Captain, my Captain!” in a dramatic show of gratitude to the liberating teacher. The problem is it never happened for us.

As a teacher, I’m acutely aware of how our national discourse—not just screenwriters—usually casts teachers as either heroic or craven, tireless or lazy, and of course that influences media depictions too. But the debate about teachers follows from our formative experiences with them. We’re all affected by the teacher dichotomy that starts forming in our minds when we’re young. Adults understandably don’t remember the process of how they learned in school so much as they remember the people right there with them along the way. We remember most what we feel most deeply, which in our school years is often our experiences of our best teachers at their best and our worst teachers at their worst. Later, a few recast those vulnerable times on screen and it all comes back to the rest of us. We remember those heroic and horrible teachers, for better or for worse.