The Origin Of The Most Famous Piece of Classical Music

You know this one, I promise.

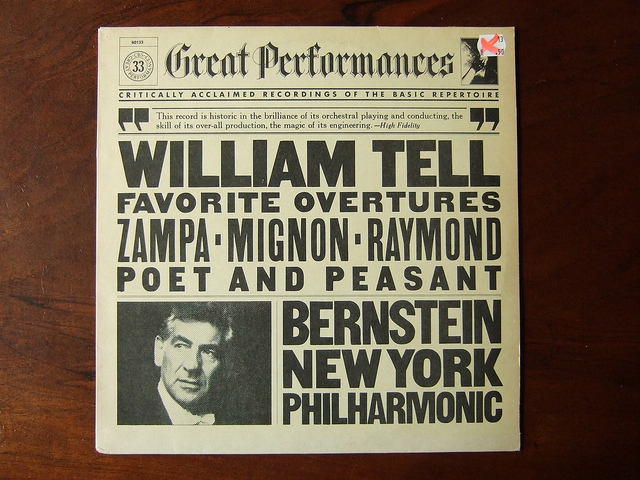

Image: Piano Piano! via Flickr

As I am sure everyone remembers and is aware of, this week marks the beginning of my 10-concert symphony subscription for this upcoming season. When I wrote about Bruckner a few weeks back, I knew that his Fourth Symphony was going to be the hallmark of this week’s concert. What I did not realize until this past week when I looked further into the program is that it also features what is probably the most famous piece of music of all time: the William Tell Overture (BERNSTEIN). Now I do not believe you if you tell me you don’t know this piece. I don’t care if you’re a philistine or an idiot or you’ve been living alone in the woods of Wisconsin for the past twenty years. You know the William Tell Overture. Have you seen a cartoon? The Lone Ranger? (The ORIGINAL, not the ARMIE HAMMER version.) Listened to music even one time? You know it.

William Tell Overture was composed by Gioachino Rossini, one of—if not the—most famous Italian composers of all time. He’s most widely known as a composer of operas; maybe you’re also familiar with The Barber of Seville? Rossini was born in 1792 and died in 1868, and William Tell (the opera for which the now-famous overture was composed) was his final opera, written in 1829 when he was only 37 years old. William Tell, his protagonist, is a famous Swiss folk character (and an answer in the New York Times crossword the other week) who defied Habsburg rule and in turn was forced to shoot an arrow into an apple placed on his son’s head. (This should all sound very familiar to you now.) He succeeded, and eventually went on to lead the Swiss against all those who would oppress them. As far as folk characters go, he’s a nice change of pace from the usual tricky idiots that a lot of classical music is written for.

William Tell Overture, like most overtures, is a compilation of themes from the larger piece; in turn, it’s divided into four sections to a point where it almost feels like a very succinct little symphony. The prelude is called Dawn. It features five solo cellos backed by the double basses. It’s, needless to say, perfect. Other versions of dawn in music verge on saccharine or sentimental. Perhaps it’s because it’s so reliant on the sound of lower strings that makes it feel deeper and slightly more troubled (it’s also in a minor key, which helps). I love how hesitant it felts, reluctant, even, to accept that it’s dawn. By the time the pizzicato kicks in to keep the pace at the 1:04 mark, Rossini has accept it’s time to stop hitting snooze and pull oneself forward into the bright morning.

The following section is aptly called Storm. Here the remaining strings and woodwinds and horns chime in for a general feeling of chaos. Time for me to admit that this is the section I’m least wild about. Something about simulated natural chaos never strikes me as more than invented conflict. Emotionally manipulative, maybe. That’s not to say it’s bad; to me it summons the least amount of natural associations and feelings. I’m like, “yup, that’s a storm all right,” and it never quite reaches the level of chaos I’d want to hear. If this is meant to symbolize the adagio in a symphony, it never reaches the same amount of depth those movements do. I zone out, to be frank! It’s fine!

The next section, Ranz des Vaches (Call To The Cows), has a rich pastoral texture to it. You may associate this one with cartoons as well, which wouldn’t be incorrect. It scores Disney’s The Old Mill cartoon in its final few minutes. Interesting and curious to have two morning-related sections in this overture but who am I to judge? The woodwinds here are very playful and sweet; this section lacks some of the aforementioned depth of the earlier morning section. That’s okay: it’s for the cows. It’s like waking up your dog because you want to play with it. It builds in both speed and texture, the flute layered just beautifully under the oboe around the 7:00 mark.

The final section, of course, of COURSE, is the world’s most famous melody. It’s almost hard to believe someone composed this very seriously and not as a prank on Western culture at large. Forever associated with horses and racing and galloping, March of the Swiss Soldiers in actuality has nothing to do with horses or charging so much as it does Swiss liberation. But that’s okay! Art means both everything and nothing, you know? In the grand scheme of this piece, it’s a fitting and wild finale. It’s frantic but never fully loses control of itself, which is in part why I think it’s remained one of the most memorable melodies. This organized chaos works much more effectively here than in the storm, probably because of its unending forward momentum, as if it is really and truly snowballing. Admittedly, after this bombastic a finale, it’s hard to remember what came before it, but that’s legacy for you.

There is a corresponding playlist for all pieces discussed in this column here.