The Bizarre Brand Hagiography of Stew Leonard's

How did a local chain of grocery stores leave such a mark?

Image: Mike Mozart via Flickr

Stew Leonard’s is at the center of one of my earliest memories: it’s the early ’90s and I’m in the back of my parents’ station wagon, which is overflowing with beach-vacation detritus. We are hurtling into an incorrigible August haze, about two-thirds of the way through the long drive from Cape Cod to our home in suburban New York. We are feeling the itch of having been confined to a car for too long—the leg-cramps, the window-glare, the constricted arm-stretches. We are approaching the point at which tempers will inevitably flare.

Out of this fraught summer landscape arises the Danbury, Connecticut exit of I-84, and not far from its exit ramp materializes a broad brown-roofed structure surrounded by a sea of parking lot. At the outskirts of this parking lot is a small barn, alongside it the genteel wooden fences of a petting zoo. And beyond this incongruously located petting zoo, at the foot of the brown-roofed structure, is a red-and-white striped awning covering an open-air restaurant and seating-area, like a family-reunion BBQ that has been mercifully opened to the public. Past this awning, at the entrance to the structure itself, is the structure’s namesake, in taught cursive and bright, unapologetic orange: “Stew Leonard’s.” Below that, in a more austere white block-font: “WORLD’S LARGEST DAIRY STORE.”

We leave the station wagon, shake our limbs, and welcome the feel of real, unconditioned air. We bound for the grill and tables under the awning (called the “Hoedown”) and slink off to the nearby bathrooms. We dine on burgers and hotdogs, and, since we are still, technically, on vacation, I am granted a small cone of rich vanilla soft-serve. We finish our meal and enter the store itself, anticipating the wonders inside.

It is the happiest any of us have been to visit a grocery store—at least since this time last year, and at least until this time next year. I am too young, at this time, to understand the strangeness of this fact—that I am treating a grocery store with the same excitement as a birthday party or a sleepover. All I know is that those bold orange letters signal a rare treat, and I walk into the building eagerly, gleefully, ready to devour the sensory experience of shopping at a Stew Leonard’s.![]() “A ‘Disneyland’ Dairy Store” proclaims the headline of a 1983 New York Times article about Stew Leonard’s, and though this honorific has become a generic descriptor for the brand’s ethos (and encouraged by Stew Leonard himself), it’s slightly off the mark. Disney conjures a corporatized, streamlined, and sterile form of amusement: focus-group branding, merchandized IP, adherence to narrative cohesion at all costs. Stew Leonard’s, on the other hand, is weird and haphazard. Out of a simple, sepia-toned concept—an old-fashioned family dairy farm—has grown something far more peculiar.

“A ‘Disneyland’ Dairy Store” proclaims the headline of a 1983 New York Times article about Stew Leonard’s, and though this honorific has become a generic descriptor for the brand’s ethos (and encouraged by Stew Leonard himself), it’s slightly off the mark. Disney conjures a corporatized, streamlined, and sterile form of amusement: focus-group branding, merchandized IP, adherence to narrative cohesion at all costs. Stew Leonard’s, on the other hand, is weird and haphazard. Out of a simple, sepia-toned concept—an old-fashioned family dairy farm—has grown something far more peculiar.

Image: mikkime via Flickr

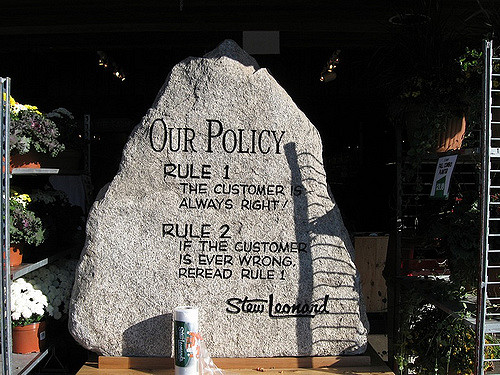

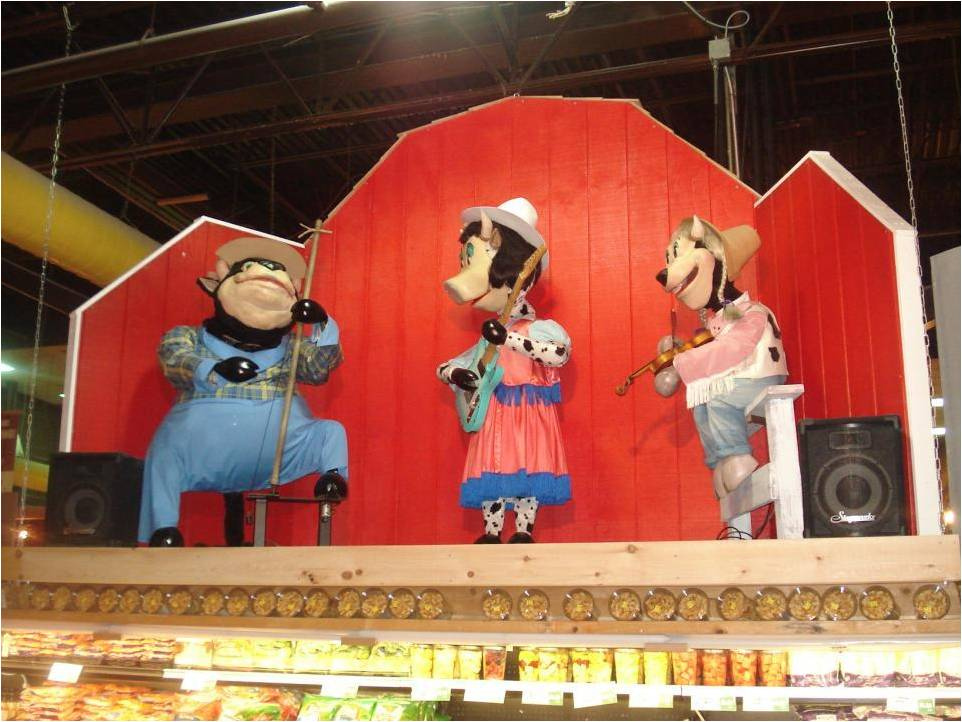

Anyone even remotely familiar with Stew Leonard’s can enumerate the things that make it what it is: the granite rock that adorns the front of each store, on which the brand’s two rules are inscribed under the header “Our Policy” (“Rule 1: The customer is always right! Rule 2: If the customer is ever wrong, reread Rule 1!”); the ice cream and other dairy specialities that can be purchased at stands outside the store, to be consumed after shopping, with a free cone due to anyone who spends more than $100—some sort of perverse meta-reward, food you deserve for having purchased food; the fact that most of the food for sale, and especially the dairy, is Stew Leonard’s-branded and ostensibly produced in-house; the fact that there are a limited number of food items stocked, compared to traditional grocery stores, a testament to the care with which Stew Leonard’s has selected these items, and the items’ superior freshness; the cow-and-chicken-suited mascots who prowl each store’s interior, like Times Square Elmos, looking for kids to accost; the animatronic displays of anthropomorphic Stew Leonard’s products arranged in bucolic settings, which dot the stores, and which, at seemingly random intervals, will come to life and regale shoppers with fiddle-infused songs about the righteousness of Stew Leonard’s and the wholesomeness of its food, usually stopping the flow of shopping carts in their tracks, so the children seated in said shopping carts can watch, slack-jawed, as the milk-carton-shaped robots wiggle and blink.

Image: k.steudel via Flickr

But the most important thing about Stew Leonard’s, the one factor in its design with a subliminal rather than audio-visual effect is the layout of each store—not as lines of parallel aisles, but rather as one long, zig-zagging aisle, from which there are no apparent escapes or shortcuts. To describe this is to make it sound so obvious, so revelatory (customers are forced to walk by everything in the store! fucking duh!) as to actually flatten the sensation of experiencing it person.

Walking through it is akin to binging a television program on a streaming service—at the start you feel no different than you would under normal circumstances, but as each episode, and as each section of the store, goes by, you enter deeper and deeper into the world being created before you, becoming inoculated to the world itself, until you are so fully immersed that you have forgotten where you began when you started. Exiting a Stew Leonard’s after shopping is like closing your laptop after crushing seven or eight or ten episodes in a row—you find yourself a little dazed, your eyes readjusting to the light, and feel a little ashamed as you hoist your bags into the trunk of your car and catalogue all the things you bought that you definitely didn’t need.![]() Those family visits stopped in the late ’90s, not because the vacations stopped, but because Stew Leonard’s came closer to home, opening its third location, and first in the state of New York, in Yonkers. The Yonkers location is directly off the New York State Thruway at a toll-interchange, perched atop a hill of other, lesser retail brands (Costco, The Home Depot.) The structure features the same brown roofing, and a large, presumably ornamental silo, on which the words “FARM FRESH FOODS” is emblazoned in green, visible from the highway. The other markers of Stew Leonard’s peculiar approach to grocery sales are of course present—an ice cream kiosk, a butcher-station with a transparent dry-age meat hanger, and a family-band of animatronic farm-cows (the “Holstein Family Singers”) looming above one of the store’s maze-like crannies.

Those family visits stopped in the late ’90s, not because the vacations stopped, but because Stew Leonard’s came closer to home, opening its third location, and first in the state of New York, in Yonkers. The Yonkers location is directly off the New York State Thruway at a toll-interchange, perched atop a hill of other, lesser retail brands (Costco, The Home Depot.) The structure features the same brown roofing, and a large, presumably ornamental silo, on which the words “FARM FRESH FOODS” is emblazoned in green, visible from the highway. The other markers of Stew Leonard’s peculiar approach to grocery sales are of course present—an ice cream kiosk, a butcher-station with a transparent dry-age meat hanger, and a family-band of animatronic farm-cows (the “Holstein Family Singers”) looming above one of the store’s maze-like crannies.

Image: Portal Abras via Flickr

The Yonkers Stew Leonard’s was located at the exact midpoint of a trip I took almost weekly, from my family’s home in the suburbs not far from the Thruway to my grandparents’ apartment, not far from the The Major Deegan (same Thruway, different name) in the Bronx. I would join my Dad on the trip down to the city each Saturday morning, helping my grandparents with their errands, and then stopping at Stew Leonard’s on the return trip back up the Thruway.

These Stew Leonard’s trips, now weekly instead of yearly, were more perfunctory affairs—ordinary grocery shopping excursions without any sheen of vacation afterglow. But there was no luster lost—the regularity of the trips yielded not a diminishing of the Stew Leonard’s aura, but an increasing appreciation of the brand’s idiosyncrasies. I became familiar with every inch of the store’s labyrinth, a connoisseur of its produce and bakery and prepared meals. Our fridge was now perpetually stocked with my favorites—the buffalo chicken salad, piquant and speckled with pungent gobs of Stew’s blue-cheese; the chocolate-chip cookies, thin and expansive, packed tightly into plastic containers, flavored expertly with just a hint of salt; the decadent eggnog, dessert in liquid form, creamy and rich and cinnamon-spiced.

Over time, those trips dwindled, until they stopped altogether. My grandparents grew infirm and passed away. I left home for college. My dad sought other, more convenient, shopping options—Trader Joe’s for specialty snacks, the local C-Town for staples, the Fairway that opened up a short drive away for protein and produce. It’s been at least seven years, maybe closer to ten, since I’ve set foot in that Yonkers Stew Leonard’s, or any Stew Leonard’s. But I can still envision the store’s layout, the contours of every kink in its one single aisle, the smells of its in-store bakery and comically large coffee-roaster. These memories are powerful and unabating, but they tend to obscure the realities that underlie them.![]() Stew Leonard’s own history, as recounted on its corporate website, is just as family-oriented and Americana-tinged as the inside of its stores. The brand began in the 1920s as Clover Farms Dairy founded by Charles Leonard, who delivered its wares by truck during the heyday of local milk-men. In the 1960s, Charles’s son, Stew Leonard himself, got into the delivery business when a new state highway was planned to cross right through Clover Farms. Over the years, Stew Leonard’s became not just a dairy but a legitimate, if bizarre, grocery store.

Stew Leonard’s own history, as recounted on its corporate website, is just as family-oriented and Americana-tinged as the inside of its stores. The brand began in the 1920s as Clover Farms Dairy founded by Charles Leonard, who delivered its wares by truck during the heyday of local milk-men. In the 1960s, Charles’s son, Stew Leonard himself, got into the delivery business when a new state highway was planned to cross right through Clover Farms. Over the years, Stew Leonard’s became not just a dairy but a legitimate, if bizarre, grocery store.

Stew Leonard, Jr. took over in 1987, and his brother, Tom Leonard, opened the second location in Danbury in 1991 (though he later left the family business to start his own offshoot, Tom Leonard’s Farmer’s Market, in Virginia.) Their sisters Beth and Jill also joined, and the company has grown slowly over the years. There is now a fourth location in Farmingdale, and fifth, which opened in East Meadow in August.

Image: Shinya Suzuki via Flickr

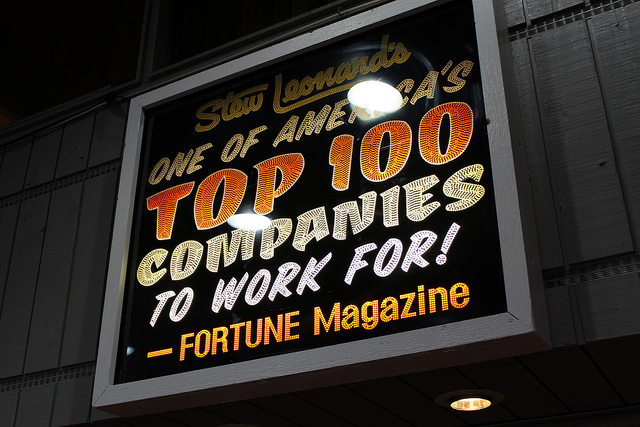

Despite its relatively small scope and regional focus, Stew Leonard’s has received various accolades and a plethora of business-world attention. It’s been named to Fortune Magazine’s list of Best Companies to Work For, and it has a Guinness Book of World Records entry for “the greatest sales per unit area of any single food store in the United States.” Stories abound of corporate titans from national brands visiting to learn Stew’s ways, and the company even offers “Stew’s Seminars,” which teach the lessons of a “World Class Customer Service Organization,” monetizing this renown.

It’s a great American Capitalist Success Story in every sense, a hero’s journey of family, persistence, and maniacal focus on the customer. And this self-mythologizing, this perpetuation of its own hagiography, is just as fundamental to the Stew Leonard’s brand as the store layout or the dairy or the abundant free-sample stations. To enter a Stew Leonard’s is to enter the Leonard family world. The proprietors’ image is plastered across the store, its message of customer-centricity and devotion to quality printed in its questionable font on the walls that face the long lines of the cash registers. I didn’t even need to visit the site’s corporate history to refresh my memory of the above outline—I’ve been imbibing it since the day I first entered a Stew Leonard’s, twenty-some-odd years ago.![]() Here’s the thing about those memories—both the ones I made at Stew Leonard’s and the ones Stew Leonard’s has fashioned about itself—they’re incomplete.

Here’s the thing about those memories—both the ones I made at Stew Leonard’s and the ones Stew Leonard’s has fashioned about itself—they’re incomplete.

The joy of visiting the Danbury location as a kid has as much to do with the Stew Leonard’s store as it does with what that long car ride represented: the slow march back from summer and into the school year. Getting lost in the circus-like brouhaha of Stew Leonard’s is a way of forgetting the feelings that surrounded it—dread, anxiety, the death of childhood freedom. It’s easier to focus on the happiness of Stew Leonard’s than it is to focus on another school year.

Image: Mike Mozart via Flickr

The Yonkers trips, too, paper over darker memories. The purpose of those regular Bronxward drives was to help my grandparents conduct their affairs after they had become unable to do so themselves. Many times, we were not even going to the Bronx but rather to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, whether one or both grandparents were ensconced. Only in retrospect did I realize I spent those trips watching my grandparents slowly die. I’ve latched on to memories of Stew Leonard’s to avoid the memories of my grandfather sitting emaciated in his armchair, unable to rise, and my grandmother using a walker to amble down the hallway to the elevator in fits and spurts, my Dad and I steadying her shaking arms.

The corporate history on Stew Leonard’s website conveniently fails to mention the years that Stew Leonard, and three of his close associates, spent in prison in the 1990’s for tax fraud. For years, Stew Leonard’s upper management executed an ingenious scheme, using sophisticated computer software to skim money from each day’s take so it could be hidden from the IRS. More than $17 million was stolen in total, at the time the largest ever computer-enabled tax-evasion conviction in America. Bags of cash were ferried out of the country undeclared on flights to Stew Leonard’s vacation estate in St. Martin’s.

Stew Leonard, Jr. was given immunity from his own involvement in a plea deal, and he continued to run the business while his father served his sentence. It was a long, embarrassing, and public ordeal, and it shattered the image Stew Leonard had worked so hard to create. Those photographs of the family and its mantras on the walls of Stew Leonard’s stores appear to also be a form of selective memory—a way of emphasizing the family’s goodness while lessening the sting of their misdeeds.![]() Though Stew Leonard’s success continues to this day, it is still something of an outlier. Trader Joe’s is quirky, and Wegmans and Fairway make similar claims to freshness and quality, but all three have expanded well beyond Stew Leonard’s reach. Whole Foods was acquired by Amazon, and the financial stresses that brought it to that point challenged its own thesis of a national grocery chain premised on the zealous ideals of natural and organic. Grocery stores as a very concept are now under attack from multiple fronts: app-enhanced delivery, meal kits, juice cleanses, and Soylent. The ritual of buying fresh food each week and cooking for oneself and one’s family is no longer a bedrock of the American home but rather a plateau to be reached only by the affluent and the committed. Stew Leonard’s is still kicking, still family-owned, building new stores, and adding new products, at a slow but determined pace.

Though Stew Leonard’s success continues to this day, it is still something of an outlier. Trader Joe’s is quirky, and Wegmans and Fairway make similar claims to freshness and quality, but all three have expanded well beyond Stew Leonard’s reach. Whole Foods was acquired by Amazon, and the financial stresses that brought it to that point challenged its own thesis of a national grocery chain premised on the zealous ideals of natural and organic. Grocery stores as a very concept are now under attack from multiple fronts: app-enhanced delivery, meal kits, juice cleanses, and Soylent. The ritual of buying fresh food each week and cooking for oneself and one’s family is no longer a bedrock of the American home but rather a plateau to be reached only by the affluent and the committed. Stew Leonard’s is still kicking, still family-owned, building new stores, and adding new products, at a slow but determined pace.

A key part of this insistent success has to do with memories that only a place like Stew Leonard’s can create. The food is good, no doubt, and the dairy is fresh and cheap, but the most compelling thing about Stew Leonard’s is what it means to be inside one of its stores, to walk through that maze of food and drink, to be assaulted by that kitschy, if overwhelming, wave of schizophrenic branding, and to submit to the ride you’re being taken on. Those memories are strange, and hazy, and manufactured. And they are clung to as a way of sublimating other memories, ones we’d rather forget. But this isn’t such a bad thing, after all. We could all use a little Stew Leonard’s to remember, from time to time, what it was like to be a child, to be in awe, and to be happy for the most ridiculous reasons.