How To Kill A Possum

Raising chickens in Oakland.

The morning after, as I filled a 10-gallon bucket with water, trying to keep my favorite work dress and fancy Swedish clogs from getting splashed with the hose, I finally got it. Killing a wild animal is very hard. And I don’t mean emotionally wrenching or internally conflicting. My ethical dilemmas about the work in front of me had been totally erased by months of insomnia, back-breaking labor and near-insane, illegal behavior. What I realized is this: it’s very difficult to whack, burn, stab, or shoot the life out of a wild creature.

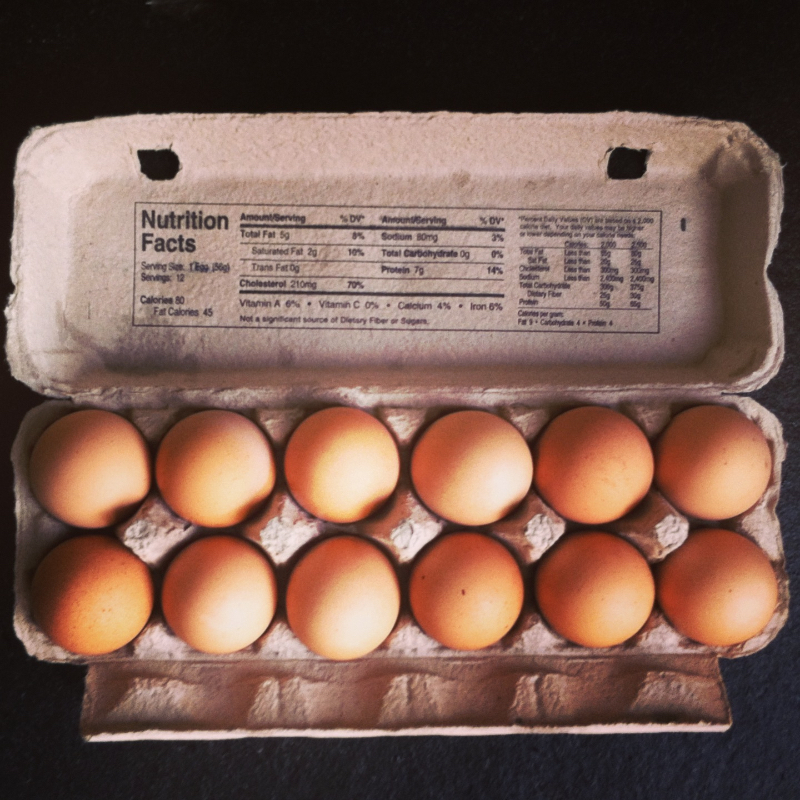

Like many people in Oakland, California I raise chickens. People here don’t raise chickens because they don’t earn enough money at their real jobs to buy eggs. Or because the eggs for sale aren’t the most bougie, sought after eggs anywhere in the United States. Every grocery store in the Bay Area is stocked with about 25 different brands of free-range, locally sourced, fertile eggs. The yolks are deep mustard orange—evidence of the greens and bugs that the chickens laying these magic orbs are eating. On any, and I mean any of the 7 days in a goddamn week, there’s a farmer’s market within a 5–20 minute bike ride where foodies like me can purchase eggs straight from a local farm, still warm from being nestled in the deep, downy folds of poultry pussy.

Heirloom hens, raised on organic greens and oyster shells from the Pacific, give birth to the most beautifully hued eggs—blue, brown, pale green, saffron, speckled. I know other chicken hobbyists who raise hens because they love the satisfaction of working for their food, of plucking the eggs straight from the coop with their own bare hands. Something in them yearns for a back-to-the-land experience they never had as a child. But not me. No, I’ve come to realize that I raise chickens because I am crazy. Because I must love to work my ass off, to lose sleep, friends, and hundreds of dollars every year.

But back to the bucket. My work, which had started the night before at 2 am, was almost finished. I was about to drown eight baby possums in a 10-gallon bucket of water.

During the day, I work at a contemporary art gallery in San Francisco as an under-paid, over-educated writer. Working at a gallery in the city means that though you have been hired to be the writer, you are also the receptionist, website expert, cleaner, bartender, property manager, dishwasher, street sweeper, art installer, sales clerk, personal assistant and psychotherapist for the gallery owner. It’s hard work, in the way that going to church or talking with one’s aging mother is hard work. There’s a lot of subtle pressure to look your best and dress up. All you can think about is how hungry you are and how much you have to pee. Your job is just to listen, nod, and humor what’s being said when you really just want to run away screaming and laughing at how maddening it is to be a grown adult, with a brain, still listening to the same ridiculous shit.

On the day I was filling the bucket, I had just written a press release about an exhibition consisting of lost cat posters the artist had torn from telephone poles. This artist’s project required me to attribute the work in the exhibit to a fictitious person, whose name was exactly the same as the artist himself. The job is inane, but it’s nothing compared to the work I’d been doing at night for several months, which had reached a new point of lunacy.

![]()

“It’s happening.”

This is the text that woke me from a deep sleep at 2 a.m. the night before the bucket incident. I knew exactly what it meant, and in a panic, I jumped out of bed. My feet found my boots. In my fight-or-flight mode, I decided there was no time for pants. I ran out the back door, into the pitch dark, using my iPhone as a flashlight. I found my roommate and life-long friend, Stacey, who lives in a little cabin in the backyard, standing in front of the chicken coop. She was using her iPhone to light and briefly stun the culprit: an enormous possum, inside the coop, playing dead.

This was not the first time this had happened. Or the second. It was around the fifth time in about as many weeks that a possum had gotten into the coop. The problem was not that the possum was going to kill the chickens. It’s that the damn thing would try to kill the chickens for hours, and might not actually succeed.

That sounds cold. But at this point, I had been raising chickens for five years, and had seen it all. I briefly considered walking back inside, putting in earplugs, and turning on a white noise machine to drown out the hours and hours of cacophonous squawking which accompanies the work of a possum trying to bring down a flock of poultry.

But then I thought of my kids. Each time they found the eviscerated body of one of their pets they had lovingly raised from little yellow fluff-balls into gorgeous, lushly feathered laying hens, their horror was fresh. The last time one died—ripped apart by a raccoon—I found my 6-year old son pointing and screaming at a purplish pile of liver, kidneys, and entrails lying outside his chicken’s flayed open belly. He had named that one Pooper. She was a Plymouth Rock, whose black-and-white speckled patterning made it look like she was strutting around the yard in a tiny tweed coat, dressed to the nines for her workday—which consisted of eating and defecating the hours away. It looked like the raccoon had unzipped this chicken like a jacket, from beak to belly, and poured its entire insides out onto the ground.

But I wasn’t standing there in my underwear in the pouring rain because I was afraid of my children’s hearts being broken once again. I had been sentimental the first few times we lost chickens. But not anymore. The worst outcome would be a damaged but not completely dead chicken, and the resulting peer pressure to pay a vet to stitch it up. Or euthanize it. I was not spending that $700 no matter what. Doing some quick math, I calculated that the vet fee represented 31 hours of writing about lost cat posters. So there we were, two women armed with nothing but master’s degrees and suburban upbringings, pointing our iPhones at a wild animal, trying to figure out what the fuck to do next.

![]()

It should be noted that this possum was just trying to do its job. Since being introduced from the East Coast to California in 1910, Didelphis virginiana (The Virginia Opossum) has been nailing the task of ensuring its survival as the only native North American marsupial in the state. Because of their short gestation period (13 days), their double mating season (Spring and Fall), and large litter size (13 on average), possums can proliferate at a fierce rate. They can adapt to a variety of environments and eat everything: fresh meat from voles, rats and snakes; carrion of any kind; fruits, nuts, vegetables, snails, insects, earthworms and trash.

But it’s not easy being a possum. At any given time, a possum has A LOT of mouths to feed. And unlike the mouths I have to feed, which I can drop off at school while I earn $22.50 an hour, possums have to bring their young to work with them. Possums carry their offspring in their pouch for 11 weeks, where the passel (the term for a possum litter) nurses almost continuously. After that, the babies cling to their mother’s back, four or seven at a time, while she brings home the bacon. Or chicken, as it was on this particular night.

About half of the passel dies in the first several weeks after birth, and if a possum does make it to adulthood, it rarely lives beyond three years. A possum’s job is made harder by the fact that its top running speed is only seven miles per hour, with a very small brain-to-body ratio. The tools of its trade include a mouthful of 50 teeth (more than any other North American mammal), a repulsive, smelly, greenish, musk-like fluid it can emit from its anal glands when it feels threatened, and an uncanny ability to play dead for so long, in such a completely catatonic state, even a smart predator with a big brain can be fooled. Possums are plagued by leptospirosis, tuberculosis, relapsing fever, tularemia, spotted fever, toxoplasmosis, coccidiosis, trichomoniasis, typhus and Chagas disease. They host a variety of lice, ticks and other parasites. Possums face more threats than you might imagine, even in Oakland: owls, hawks, foxes, coyotes, cats, dogs, and, since roadkill is a favorite food, cars.

Not to mention humans. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife considers possums non-game animals, which means that if you are the owner or tenant of a property, you may “control” the possum by any legal means.

The last time I had killed a possum, about two months earlier, it was gross, but definitely legal. I was in my garage, reaching inside a cardboard box to pick up one of the three chicks we were raising under a heat lamp. I was checking for vent gleet, otherwise known as “pasty-butt.” The job involves picking shit out of the anus of each chick to make sure this critical vent to their system isn’t clogged. This task of keeping a chick alive is usually done by a mother hen,unless you’ve taken those chicks away from her to raise them in your garage. Apparently, chicks can’t clean their own butts, and if someone doesn’t do it, they can’t poop or pee, which causes death within hours. The chick’s only job is to look so cute and helpless that it can motivate a busy human, with a non-farm full-time job, to wipe three little poultry buttholes, five times a day.

When I went to pick up the third chick, I screamed. It was not a chick sitting there all nestled in the hay, but a possum, so full from eating the third chick it could barely move. I considered my options. Option 1) Try to shoo it out the hole it had gnawed in the box and let it go, or Option 2) Kill it. Option 1 would result in a high likelihood of the possum coming back for another round of snacking. Though chicken loss was old hat to me at this point, I was pretty invested in this batch, having spent so many days with my finger up their assholes. Not to mention the money I’d dropped on organic chicken feed, hay, thermal warming lights and a specialized waterer to keep the chicks from drowning themselves while trying to drink.

So I grabbed a long-handled shovel, the only weapon at hand, and prepared myself for Option 2. I gathered myself for the work any chicken farmer worth her salt must have to do all the time. I took a deep breath and brought the sharp head of the shovel down on the possum’s neck as hard as I could. Slam. This did almost nothing. The possum hissed, showed me its mouthful of dripping teeth, and emitted one of the rottenest scents I have ever smelled. I hit it again. Wham. The possum was wounded, but still very much alive. I had to ram the blade of the shovel into the head of that animal about 30 times before it actually died. My pulse was racing. I was hot, sweating, shaking and exhausted from the effort.

![]()

I was raised in suburban upstate New York by parents who reveled in the convenience of grocery stores, microwaves, and Chinese take-out. The only mental preparation I’d had for this task was watching Game of Thrones with my boyfriend in bed night after night, falling asleep to the sounds of battle axes and Valerian steel being sunk into skulls and torsos, warmed not by my own adrenaline-fueled exertion but by the laptop burning a hole in the duvet cover.

But two months later, on this night, standing in the pouring rain, addressing the problem at hand with an Apple product like any other inept and over-privileged American, I realized the situation was more complicated. This possum was caught in a trap of my own making. The chicks from the garage that I had so lovingly and gruesomely saved pasty butt and possum had survived to become pullets—young hens, ready to join a regular coop full of their peers, but not yet mature enough to lay eggs. One morning, I walked into the backyard to find that one pullet had disappeared. Gone. A disturbing number of feathers were scattered around the yard, but that was it. It seemed more like the work of a fox or a raccoon than a possum. Angry and frustrated about spending so much time and money to feed some predator instead of my kids French-toast addiction, I went to the hardware store, to spend more money and time. I bought 60 feet of chicken wire and a staple gun, crawled under my poop-encrusted chicken coop, and lay on my back for an entire afternoon. I reinforced weak spots and closed gaps. I double layered the wire all around the perimeter of the coop for added protection. I emerged with 10 spider bites, a pinched nerve, and angry, red scratches all over my arms, face, back and neck.

“She’s stuck as fuck, huh?”

This was my brilliant assessment of the problem in front of me. Stacey wearily nodded, the water pouring in streams off her hair. The rain was coming down, harder now, in sheets. My obsessive-compulsive staple-gunning had created a situation where the possum, which was enormous, was trapped by layers of chicken wire. It had squeezed its body inside the coop, but couldn’t get out. There was no room, much less any leverage space for my shovel-wielding Grim-Reaper move. My target was almost completely inaccessible by any means I could think to use with lethal force.

Except a gun. All I could think of was how badly I wished I owned one. As a politically liberal single mom, raising three boys in a gun-plagued neighborhood in Oakland, this was the most ridiculous thought I’d ever had. If I could, I would literally erase the second amendment from the Constitution. I wished the NRA and the gun lobby would go fuck themselves. Gunfire is the background noise of our life. It’s the cause of hundreds of injuries and deaths in Oakland every year, and even when the bullet doesn’t hit its mark, the random gun fire which manages to leave the living alive and physically unharmed is still a constant source of psychological stress and worry for me. The police and the City of Oakland, trying to do their job, have made it illegal for “anyone, at any time, to fire or discharge, or cause to be fired or discharged, any firearm or any projectile weapon within the limits of the city.” Thank God. Except here I was, wishing to do just that.

The only person around I knew who owned any kind of a gun was my boyfriend. I had seen a BB gun in his art studio. BB guns fall under the projectile weapon category of the above city ordinance. Despite everything I knew and supported about the dangers of toy guns, I threw on my oldest son’s swim parka, got in the car, and drove over to my boyfriend’s house to retrieve the weapon. When he opened the door, my boyfriend took one look at the most unsexy trench-coat/lingerie ensemble imaginable and gave me a look that said, “No. I’m not coming over to help you. I’m so glad I decided not to sleep at your house tonight. P.S. I think we’re breaking up soon.” He did the work of a guy whose knows, deep down, he shouldn’t be dating a single mom with three young boys: he handed me the loaded BB gun and shut the door.![]() I returned to the backyard triumphant. Stacey looked a little worried. She was doing the job of an accomplice who wants the target dead but lacks the cold-blooded killer instinct to actually pull the trigger. She spotlighted my hit. I cocked the gun, and fired. The possum reacted as if I’d flicked some water in its face while doing the dishes. For all the horror stories I’d read and heard about BB guns, I was incredulous at how ineffective they were at inflicting mortal injury or death. I shot again. And again. And again. I emptied an entire barrel full of shot into the possum, aiming for its head. After 50 pulls, I ran out of BBs. The possum did wake from the dead enough to hiss and snarl, but other than totally pissing it off, the BB gun had no effect whatsoever.

I returned to the backyard triumphant. Stacey looked a little worried. She was doing the job of an accomplice who wants the target dead but lacks the cold-blooded killer instinct to actually pull the trigger. She spotlighted my hit. I cocked the gun, and fired. The possum reacted as if I’d flicked some water in its face while doing the dishes. For all the horror stories I’d read and heard about BB guns, I was incredulous at how ineffective they were at inflicting mortal injury or death. I shot again. And again. And again. I emptied an entire barrel full of shot into the possum, aiming for its head. After 50 pulls, I ran out of BBs. The possum did wake from the dead enough to hiss and snarl, but other than totally pissing it off, the BB gun had no effect whatsoever.

I thought about asking my neighbors for a real gun. Though I didn’t know for sure, I suspected they owned one or knew someone who did. I was reluctant to wake them up for this favor for obvious reasons—the least of which being the burning looks they directed my way ever since “The Rooster Incident.” That particular crisis, which had just been resolved last week, had resulted in about 10 nights of neighborhood sleeplessness caused by, you guessed it, my chickens.

You see, the last chick from the garage turned out to be a rooster. Because I’m only just a wanna-be farmer, I had never seen a teenage rooster before. I thought I just had an unusually large, extremely aggressive hen, who was a late bloomer getting her period—hence the lack of eggs coming out of her cloaca. What I had instead was a boy. The rooster, named Sizzles, turned out to be a mixed blessing. Once he reached maturity, he kept everyone within a 2-block radius up all night long with incessant crowing and squawking. I thought this was some sort of temporary rooster-puberty behavior. Weren’t roosters just supposed to crow at the crack of dawn? Wasn’t this all just a raging-hormones phase?

To appease my neighbors and my youngest son whose pet it was, I desperately tried to find Sizzles a new home before someone called animal control to have it taken away and destroyed. Unlike hens, it’s illegal to keep a rooster in Oakland. All day at work, I discreetly searched my browser for “bay-area-chicken-sanctuaries-near-me” in between trying to write something deep and meaningful about the gallery’s upcoming show: Sic Transit Gloria Mundi (a.k.a. Extremely Uncollectible Mural-Sized Oil Paintings of Sad Clowns).

I never considered the possibility that Sizzles was crowing all night for a good reason. On the day I went into the coop to coax him out (I had found a home for it on a real farm where they actually wanted one) I realized Sizzles was crowing because he had just been doing his job, all night, every night. His feet and legs were bloody and scabbed, covered with tiny bite marks. The rooster had been protecting the flock from possum attacks, squawking and pecking and jabbing until the possum gave up and came back again the next night. When I told this story to the farmer friend who was taking the rooster, she said, “Huh. No shit. Duh! That’s why I want it.” She offered me a hen in return for the rooster. I declined.

What now?!? Stacey and I were both freezing cold and exhausted. The possum, though now playing dead again, was still a threat. I wanted so badly to walk away.

I had a brainwave. “I’m getting the blowtorch!” Brilliant! I could burn the possum. Fire could reach through wires; it knew no boundaries. Stacey has seen me through three kids, a divorce, and twenty years of life’s messy situations, most of which I had created myself. She knew when I was in over my head. She nixed the blowtorch, citing the threat of being convicted of arson, which could result in homelessness for us all if things got out of control.

I pathetically consulted my iPhone for ideas, but realized it had done its job: illuminated the problem, and Googled the crap out of it. But as of yet, there isn’t an app that can kill things. Now it was time for me to do my job. Nobody was going to take care of this problem but me, and so far, I had been failing miserably. I had one idea left, and as much as I hate to admit it, it had come from my boyfriend. Lying in bed one night, soon after the “Rooster Incident,” listening to me go on and on obsessively about the possums and how to protect the flock, he told me he had read online about someone who had duct taped a butcher knife to the end of a broom handle and stabbed a possum to death.

This was my last, worst/best idea. I found a broom and duct tape. I went into my oldest son’s top drawer and took his fixed blade knife—the one he used at summer camp to carve a beautiful wooden spoon out of driftwood, with which to eat a soup he had made out of foraged herbs. I had found my murder weapon.

After taping the knife securely, I managed to find a good angle and brought the broom-spear down with all the force I could muster, as close to the possum’s heart as I could estimate. I barely pierced its skin. If I had been thinking, I would have sharpened the knife first, but now I was just committed to using the wrong tool for the job. It was terrible. I stabbed and stabbed and stabbed, grunting and screeching a little with the effort. At one point, the possum grabbed onto the knife with its teeth and had enough life left to gnaw at the tape with such ferocity I thought it would wrest the knife from the broomstick.

After about 15 minutes of jabbing, extracting, wriggling the spear and my body back into position, finding a good angle, and trying again, the possum emitted a stench so bad I almost barfed. The poor creature breathed its last, and went totally limp. I saw its blood on the knife and some of its guts in the mud. It was 4 am. I threw my spear into the grass, and collapsed onto the ground. Stacey, like the good friend she is, said, “That was so badass,” when really what she meant was, “I can never look at you in the same way again.” I went inside, took a hot shower, and fell into bed. I was too tired to deal with the carcass. It would have to wait until morning.

![]()

I woke up the next day, late. Bleary-eyed and weak from the night before. My body ached. There was no time to make three lunches and deal with the mess in the backyard before work. As we walked out to the car, I forbade the boys to go in the backyard until I had “cleaned up some stuff.” At this point, the three of them knew what this meant, and they were more than happy to pretend as if nothing was up. All day at work, all I could think about was how terrible the sopping wet, dead possum was going to smell, lying in a puddle of fetid water and baking in the hot sun for eight hours. When we got home, the odor hit me before I even reached the backyard.

But what I found was worse than the stink of fifty New York City dumpsters in the dead of summer. The dead possum was still there, but crawling around it were the live bodies of her eight offspring. They had been hiding in her pouch, probably nursing throughout the entire incident the night before. I thought the possum was big, but not pregnant big. My heart sank. The babies were tiny, helpless, and sneezing—the only sound possum joeys can make when in distress. Their bodies, totally covered with hair, were about the size of mice. Eight tiny tails. Sixteen bright pink ears. The buds of four hundred teeny-tiny, white teeth, pushing through the gum lines of a doomed group of orphans.

I had to act fast. My kids would let me clean up a dead possum without batting an eye. But if they saw eight, adorable, defenseless babies crawling and sneezing on their dead mother, it would be a horror show. I had to kill them. It felt terrible to let them dehydrate or starve to death, or succumb slowly to one of our housecats—batted around for hours before being eaten. Still wearing my work dress and ridiculously impractical, silver strapped wooden clogs, I grabbed a 10-gallon bucket and filled it with water. I found my middle son’s shark-chomper stick toy. I grabbed each tiny sneezing possum, plopped it into the bucket, and covered the top with an old piece of plywood. When it was over, I put all eight bodies, along with their mother, to rest in the municipal green bin. Thank God for Bay Area household composting. At least the work of burying the dead would be done by someone else.

Allison Stockman is writer who spends all her hard-earned money on overpriced coffee and pizza in Oakland, California.