Ninety-Eight Years of Fallen Women

The history of confessional magazines.

“For what am I to myself without You, but a guide to my own downfall?” —St. Augustine, Confessions

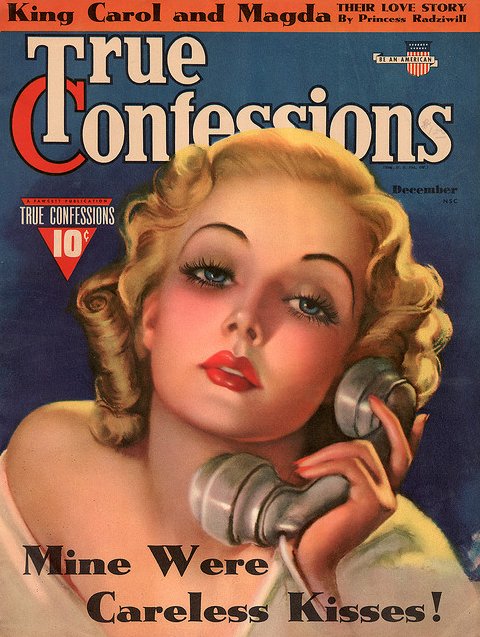

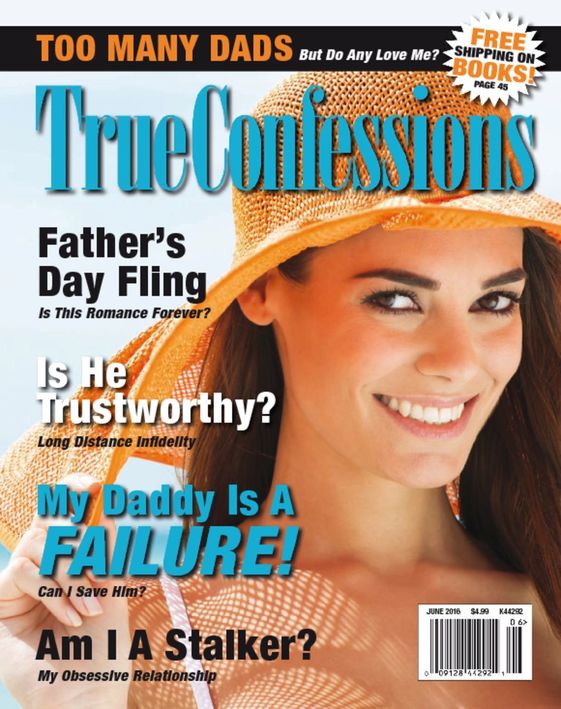

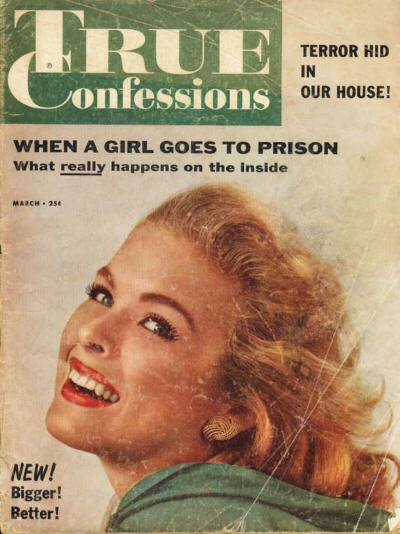

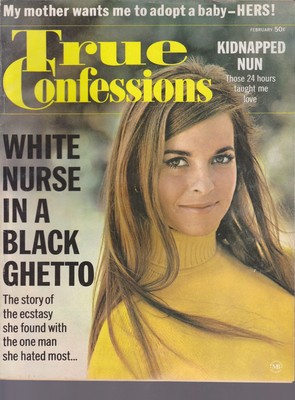

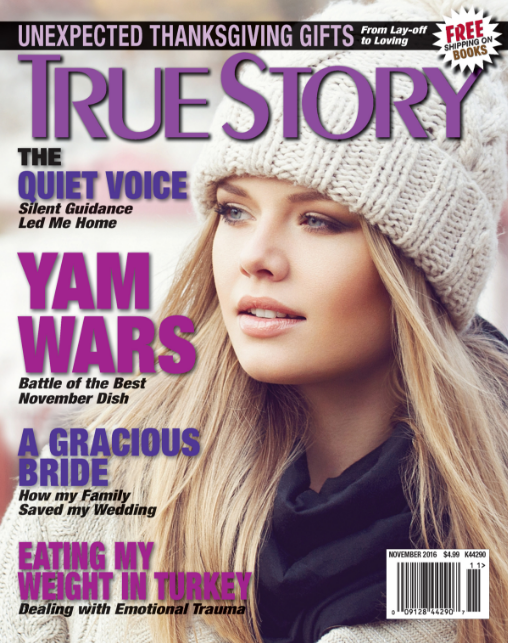

If you’ve been to the Union Square Barnes and Noble, there’s a decent chance you’ve seen True Story or True Confessions before—they’re on the magazine rack in the literature section, next to the Starbucks. The cover model is always a smiling, seasonally appropriate white woman, and the copy is generally funny in the style of a de-fanged Reductress headline. “YAM WARS,” read the November 2016 Thanksgiving issue of True Story. “So Many Dads…But Do Any Love Me?” read the June 2016 Father’s Day issue of True Confessions.

The magazines are staple-bound and always 64 pages long—ten stories, two “Inspirational Mini-Stories, and one recipe, released once a month. The paper inside is newsprint, the photos all stock images, and the prose leans toward Kindle single. They’re not exactly the kind of magazines that anyone would describe as “venerable” at a glance, but the goofy covers belie the publications’ age and legacy. The first women’s confessional magazines, True Story and True Confessions are now approaching their centennial.

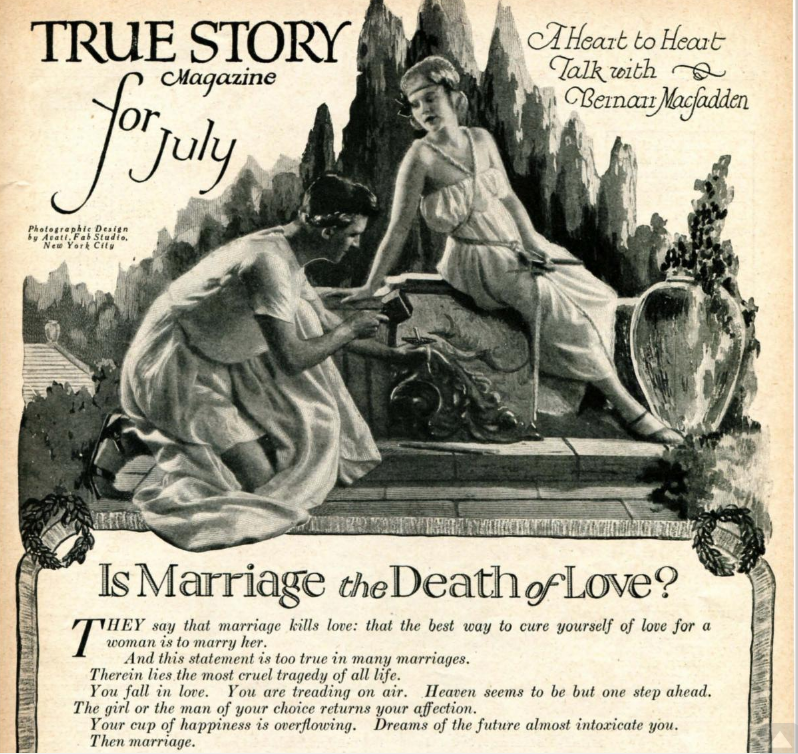

Founded in May of 1919 by publisher, Bernarr MacFadden, True Story was actually his wife’s idea. “Broken-hearted women sent [MacFadden’s Physical Culture magazine] letters after they had done two hundred knee bends, twice a day, and thrown away their corsets, only to find that the Greek gods wouldn’t give them a tumble,” Mary MacFadden wrote in her memoir of their life together, Dumbbells and Carrot Sticks. “These are true stories…Let’s get out a magazine to be called True Story, written by its readers in the first person….The idea has a correlative force. I studied correlativity in school…It’s the kind of thing that helped make the British Empire.”

She was right. Born Bernard McFadden in Mill Spring, Missouri in 1868, her husband was a small, sickly child until he was orphaned at the age of eleven and sent to work on a farm. He spent the rest of his life obsessed with strength and fitness, becoming a personal trainer and going so far as to change his name to Bernarr MacFadden because he believed the alternate spelling suggested a certain leonine masculinity. In 1913, he sponsored a search for “Great Britain’s Perfect Woman,” in a less-than-subtle attempt to find (a third) wife and Mary, a millworker and champion swimmer 25 years his junior, won. According to her memoir, he proposed in the middle of a jog.

At the time, Bernarr was already presiding over a somewhat dubious fitness empire (he was, among other things, an evangelical anti-vaxxer and the founder of The Coney Island Polar Bear Club) but it was True Story that made him a millionaire. The first issue featured a man and a woman glaring at each other, “And Their Love Turned to Hatred!” printed across the cover. The monthly magazine was an immediate hit and a pioneer promotionally—targeting the heretofore untapped market of working-class women or, as the Saturday Evening Post dismissed them, “MacFadden’s anonymous amateur illiterates.”![]() Headquartered in Manhattan, True Story was initially composed entirely of reader-submitted material—Mary MacFadden writes that clergymen were brought on board as “moral censors,” signing affidavits attesting to each story’s veracity. It doesn’t seem the clergymen did any actual fact-checking; their presence was essentially a marketing ploy to assure the public that the stories had been organically received and met their standards of decency. At the time, Bernarr was embroiled in a feud with Anthony Comstock, a proto-Giuliani who founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Horrified by MacFadden’s “Monster Physical Culture Exhibition” (Men and women exercising in leotards), Comstock had him arrested for public indecency. The two men hated each other for the rest of their lives—and True Story became an attempt on Bernarr’s part to demonstrate that he too could be a guiding moral force.

Headquartered in Manhattan, True Story was initially composed entirely of reader-submitted material—Mary MacFadden writes that clergymen were brought on board as “moral censors,” signing affidavits attesting to each story’s veracity. It doesn’t seem the clergymen did any actual fact-checking; their presence was essentially a marketing ploy to assure the public that the stories had been organically received and met their standards of decency. At the time, Bernarr was embroiled in a feud with Anthony Comstock, a proto-Giuliani who founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Horrified by MacFadden’s “Monster Physical Culture Exhibition” (Men and women exercising in leotards), Comstock had him arrested for public indecency. The two men hated each other for the rest of their lives—and True Story became an attempt on Bernarr’s part to demonstrate that he too could be a guiding moral force.

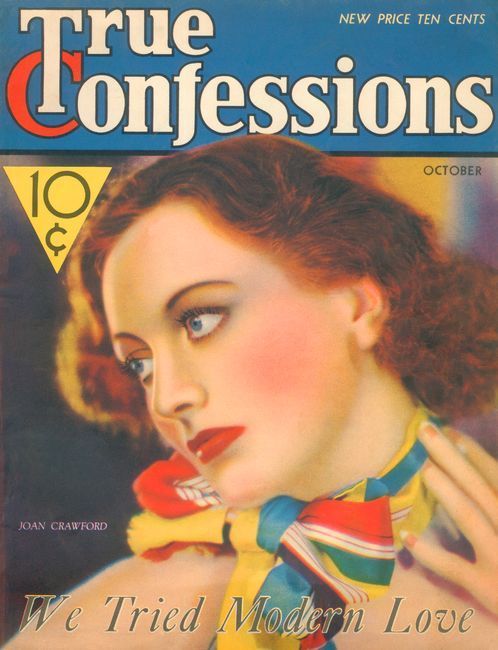

According to sociologist George Gerbner’s 1958 study, “The Social Role of the Confession Magazine,” there were about forty romance/confession magazines on the market by the year 1950, with a circulation of about sixteen million. Sold primarily in small, Southern and Midwestern towns, the median family income of a confession reader was $3,600 [about $33,610 in 2017] a year. Eighteen percent of confessional readers had not finished high school, only five percent attended college, whereas comparable figures from more upscale publications, such as the Ladies Home Journal and McCall’s, show 30 percent of readers holding a college degree. True Story remained the frontrunner among the magazines, with True Confessions—a copycat founded in 1922 by Fawcett Media Group and later purchased by MacFadden—as its closest competitor. What became known as the MacFadden’s Women’s Group eventually expanded to include: True Story, True Confessions, True Romance, True Experience, Modern Romances, and True Love. The public wanted pathos, so MacFadden Publishing hired writers to keep up with demand—in his 1934 memoir, Trial and Error, pulp writer Jack Woodford, revealed that many women’s “confessional” writers, himself included, were often simply male freelancers.

What ostensibly began as an effort to give a voice to the female underclass was quickly co-opted by men and capitalism. Gerbner quotes extensively from an incredibly interesting and insulting booklet, written by True Story Editor-in-Chief, Fred Sammis, entitled The Women That Taxes Made: An Editor’s Intimate Picture of a Large but Little Understood Market. Distributed internally at MacFadden in 1950, it was meant to codify the editorial directive. “Central characters must come from workshirt backgrounds,” Sammis wrote, “Our heroines are waitresses, wives of mechanics, file clerks—not heiresses or glamorous career women…[they are] usually not college girls.” Writers are told to imagine the reader as “a homemaker whose idea of decor extends as far as the large flowers on her wallpaper and no further.”

The theory was that the safeguards of The New Deal had vaulted these women out of desperate poverty into an anxious and aspirational lower middle class. “The new ‘woman that taxes made,” Sammis writes,

no longer cries herself to sleep with problems like ‘the roof leaks,’ or ‘I can’t pay the doctor bill,’ or ‘we can’t afford this new baby’….These new women from the homes of labor find the white collar world strange, uncomfortable. Uncertain, often bewildered in their new roles, they have a burning interest in ‘reading how other women—like themselves—solved their problems.

(This wasn’t entirely true. While The New Deal did reduce inequality, its effects weren’t felt equally across the country. Abortion was illegal, redlining was rampant, and Jim Crow laws were firmly in place across the South. As Kim Phillips-Stein outlines in her recent book, Fear City, Cities like New York, which tried to address and alleviate these issues by creating a social safety net to give the poor a fighting chance, were later excoriated for their “irresponsibility” when the national economy took a dive.)

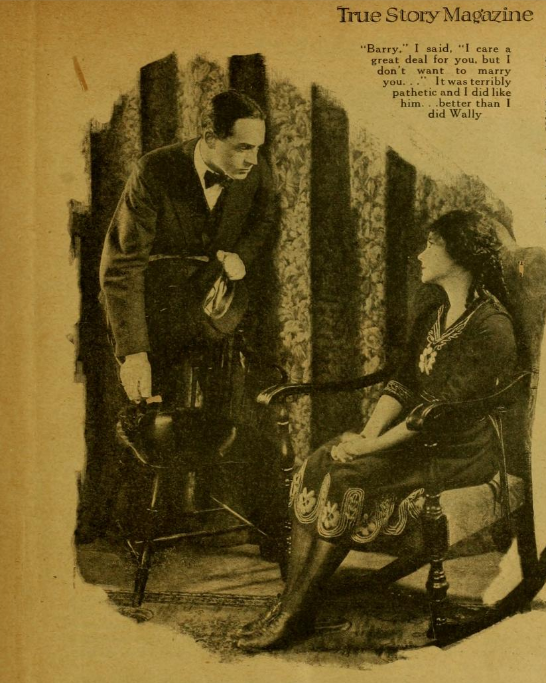

Image from July 1922 ‘True Story,’ via the Internet Archive

The first issue of True Story was released just over a year before women got the vote. The MacFadden group saw which way the wind was blowing and created an imaginary working-class woman—content, complacent, and malleable—in order to appeal to advertisers. While many of the Women That Taxes Made were absolutely still crying themselves to sleep over not being able to afford another baby, misery in the confessional was nearly always framed as the fault of the heroine rather than society at large.

The stories were, as George Gerbner wrote, designed to draw readers in with the signifiers of poverty while making “social protest appear to be out of place, unrelated to the insecurities of working-class life….making her act of defiance a crime or a sin; in making her suffer long and hard; in making her, not society, repent and reform, in permitting her to come to terms, and not to grips, with the ‘brutal world’ in which she lives.” In 1954, The Woman That Taxes Made, was printed up in several major newspapers in a push to attract advertisers. “Make ‘Em Eat Cake,” read the headline in The Detroit Free Press “…and There Won’t Be Any Breadlines!”

Image from February 1921 ‘True Story,’ via The Internet Archive, Library of Congress

“Keep her in line and make sure she buys American” essentially became the magazine’s mission. Sammis’s booklet went so far as to encourage True Story writers to intentionally undermine female participation in the labor movement—warning them that the working class woman “is exposed, far more than her white collar sister, to demagoguery, labor agitators and radical philosophies!” He considered it the magazine’s duty to keep these women away from seditious influences and in line with market forces. In his 2012 book, Confessional Crises and Cultural Politics in Twentieth-Century America, Associate Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Kansas Dave Tell suggests that “the progressive immiseration of the working class can be indexed to the progressive certainty with which True Story was understood as a confession magazine.”![]() Narratives followed the basic structure of Sin, Suffer, and Repent; obedience—to both men and circumstance—was generally the central lesson. The stories were bracketed with helpful sidebars such as, “Are you adored—or abhorred? Your disposition makes the difference!” and “You Can Live Down a Bad Reputation!” As sociologist, Wendy Simonds, pointed out in a 1988 article, “Confessions of Loss: Maternal Grief in True Story,” there was a decidedly Gothic theme,

Narratives followed the basic structure of Sin, Suffer, and Repent; obedience—to both men and circumstance—was generally the central lesson. The stories were bracketed with helpful sidebars such as, “Are you adored—or abhorred? Your disposition makes the difference!” and “You Can Live Down a Bad Reputation!” As sociologist, Wendy Simonds, pointed out in a 1988 article, “Confessions of Loss: Maternal Grief in True Story,” there was a decidedly Gothic theme,

Women are constantly the victims of situations in which they feel trapped or helpless. Unlike Gothic heroines, whose behavior is usually above reproach under uncontrollable and miserable circumstances, True Story heroines often lose control [and] adventures are stripped of the usual elegant Gothic trimmings. Instead of the young, orphaned governess…the True Story heroine might be married to a plumber, who continually gets drunk and beats her.

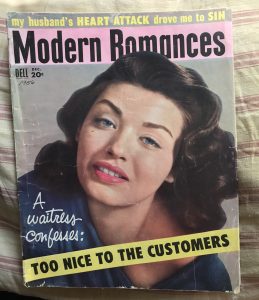

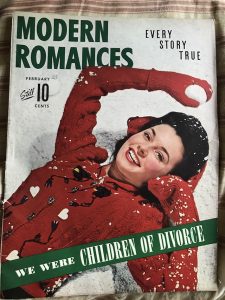

December 1956 ‘Modern Romances,’ February 1943 ‘Modern Romances’

The heroine falls in love with someone she’s not supposed to. She runs away from a stifling home environment and gets too drunk. Her ‘vanity’ leads her to dress provocatively. Simply put, she’s human—but the end result is always disaster. Women in the confessional are allowed to be brave in defense of their children. They can bravely face interminable domestic boredom, bravely stand by a husband who hits them and/or drinks away his paycheck. They can display strength in adversity so long as they are the normative, stabilizing force. But if they act out on their own behalf—whether it’s for love or want of adventure—they will end up pitiful, (even more) impoverished, desperate, and alone. “Life is cruel and dull,” Gerbner wrote of the True Story message in the ’50s. “About the only thing you can figure out is the monthly payment.”

The Fallen Woman destroyed by a single, foundational sin—“lipstick on a highball glass,” for example—is an old and worn out trope that, at their worst, the MacFadden confessionals did everything in their power to enforce. In the paradigmatic confessional story from the ’40s, “Dirt Poor and Desperate: We Traded Our Baby for a Tractor,” Luly works in a boarding house until she falls in love with Harry, a kind “dirt farmer.” They are poor but happy, until their mule breaks its leg and their eldest son dies. Struggling to pay for the funeral, unable to work the farm, and hoping to give their infant son a better life, Luly impulsively offers to trade him to a wealthy, childless couple in exchange for their tractor. She and Harry are soon thereafter arrested and charged with human trafficking.

In “My Own Story of Love,” from the 1920s, our heroine, Jean, is orphaned at an early age and sent to live with her uncle. Restless and lonely, she persuades him to allow her to take a business course in the city. “I little dreamed that the city was to offer tragedy rather than business training,” she says. This is a recurring theme—market research indicated that most readers lived in towns of populations under 25,000, so The City always signifies disaster. Three pages in, Jean is pregnant, abandoned by the father of her child, and has been placed in a mental institution after a panicked suicide attempt. “I knew I was sane, but I became obsessed with the idea that I might lose my mind through association,” she says. “Could it be possible, I cried to myself, that in a civilized country such a crime against a helpless person was permitted?”

![]() By the late seventies, an editor named Florence Moriarty had taken over the magazines. Moriarty began her career at Modern Romances in the ’50s, moved to True Confessions, and eventually rose to Editor-in-Chief of the MacFadden Women’s Group. Under her reign the magazines softened considerably, although the headlines, (“I INHERITED MY SISTER’S DEVIL CHILD” and “PLEASE ARREST MY WIFE”) remained pretty dramatic. “I never believed that if you sinned you necessarily had to suffer,” Moriarty told the Washington Post in 1978. “Some people, you know, do not suffer. Many of the magazines did indeed once have that kind of premise. And it’s a big bore.”

By the late seventies, an editor named Florence Moriarty had taken over the magazines. Moriarty began her career at Modern Romances in the ’50s, moved to True Confessions, and eventually rose to Editor-in-Chief of the MacFadden Women’s Group. Under her reign the magazines softened considerably, although the headlines, (“I INHERITED MY SISTER’S DEVIL CHILD” and “PLEASE ARREST MY WIFE”) remained pretty dramatic. “I never believed that if you sinned you necessarily had to suffer,” Moriarty told the Washington Post in 1978. “Some people, you know, do not suffer. Many of the magazines did indeed once have that kind of premise. And it’s a big bore.”

Reader demographics remained the same during Moriarity’s tenure—a blurb from a 1988 media kit, “Blue-Collar Women and Brand Name Products,” claimed that the blue-collar woman depended on popular brand names for “status recognition” from their husbands. According to a 1986 Mediamark profile, True Story had just under 6 million subscribers and about 86 percent of them were female. Median income for female readers, a third of whom were heads of households, was $9,388 [$20,967 in 2017]. Only three percent made more than $25,000 [$55,836 in 2017] a year. Confessional writers were still made to sign affidavits, but Moriarity was ambivalent about the stories’ veracity. “I like to compare it to the day Lincoln was shot or the day Christ was crucified,” she said. The Post described her office as “decorated with pictures of a lot of cats.”

That any of the MacFadden Confessionals have survived into the twenty-first century is a minor miracle. Bernarr MacFadden died in 1955 at the age of 87, leaving behind a publishing empire and (allegedly) an enormous amount of cash buried around the country. MacFadden Publications merged with Sterling Magazines in 1991 and Sterling/MacFadden was bought out by Dorchester Media Group—the self-described “oldest independent mass market publisher in America”—in 2004. When Dorchester went bankrupt in 2012, the outcry from devoted True Story subscribers was strong enough that five former Dorchester employees founded True Renditions LLC to keep True Story and True Confessions—the sole surviving magazines—alive. The current CEO, Frances Adrian, has been with the magazines since 1981—initially as an art director. When she started they had over a million subscribers. By the time they were bought by Dorchester they were down to half a million, they currently have about five or six thousand subscribers. Subscriptions make up most of their income, but the according to their media kit—which Adrian warns me is very outdated—38 percent of magazines are sold at “Mall Book Stores,” 22 percent at Walmart/Target, and 20 percent at Grocery Stores. 95 percent of readers are women.

The magazines still have a working-class bent, but the stories and circumstances aren’t quite as grim, and the writing is often pretty funny—albeit unintentionally. According to Adrian, the subscribers and the writers are primarily older Midwestern and Canadian women, many of whom have been reading the magazine for sixty years. The magazine’s advertising focuses on ads for Jitterbug phones and collectible ceramic cat plates and the stories often read as if your grandmother is writing fanfiction about you. “At least I could get on my social networks and feel connected,” says the protagonist of “I’ve Been Catfished!” (True Story February 2017) as she skips a New Year’s Eve Party and immediately falls victim to a catfishing scheme.

The modern-day True Story heroine is usually putting herself through business or management school—they always have very practical majors—generally by working as a waitress or a gas station attendant. In “Burning Love: Too Hot On Valentine’s Day,” (True Confessions, February 2017) Money is tight and Brandi is looking forward to a romantic Valentine’s Day dinner with her devoted boyfriend, Hank, until Hank accidentally lights her on fire. “The flame had likely been attracted by my cheap hair gel, which probably had a high alcohol content,” Brandi explains, helpfully. “Luckily, we found a small clinic nearby that accepted my insurance.” Brandi recovers and they live happily ever after.

In “My Secret Valentine: A Disastrous Date,” the conflict revolves around a newspaper’s Valentine’s Day dance—a terrifying premise in and of itself. Our heroine, Tara, doesn’t have a date, and resents her coworker, Felicia, whom she considers a slut. “No man was safe from the wiles of Felicia.” Tara begins receiving notes and flowers from Wallace, who has just moved to town and taken over as “Chief Editor.” Just as it looks like they’re about to make out (No one in True Story ever makes out, they just wake up a week later, miserable and pregnant), Felicia bursts in and reveals that Wallace is actually married with kids. “Heck,” says Felicia. “I didn’t get hired as an investigating reporter for nothing. If there’s ever a sexy guy that comes into our town, you’d better believe I’m going to check him out.” Tara goes to the dance with a friend and gains a newfound respect for Felicia, whom she now considers a discerning, well-informed slut.

“Happy endings always make people feel better,” Adrian told me over the phone.

Even at its worst, True Story was never as simple as it seemed. The initial marketing strategy, like many others, was based upon the assumption that the women reading these stories were easily manipulated—primarily because they were women, but especially because they were low-income and uneducated. Even Gerbner’s very sympathetic study doesn’t consider the possibility that True Story’s didactic efforts were not as effective as they’d hoped. The happy endings and their correlative morality lessons always felt tacked on, a few sentences thrown in at the end, warning the reader not to repeat the heroine’s mistakes.

No one was there for that shit, they were there for the pain. No matter how clunky the delivery pain in the confessional is immediately recognizable—raw, unrelenting, and impolite. Towards the end of the 19th century, the subject of maternal loss—miscarriages, stillborns, dead children—began to fade from more mainstream women’s magazine’s such as Godey’s Lady’s Book and Peterson’s. “Motherhood,” wrote Simmonds, “especially ‘failed’ motherhood, had become an inappropriate topic for magazines that focused on elegant, sophisticated courtships and what to wear during them.”

![]()

It’s impossible to tell which stories were written by freelancers and which were organically submitted, but love in the confessional, whether it’s good or bad (usually bad), often seems like a cover for what the writer is really trying to say. “The romance-confession path to ‘happiness’ is long and rocky,” Gerbner observed, ruefully. “And it leads through hell. The agony of the journey is made plausible only by the underlying assumption that life can be terrible if we grant that the world is a hostile jungle.” Lost children, not wanting to have children, not being able to afford to go to college, not being able to afford to leave a shitty town—all of it concealed beneath affection for a series of bland, handsome men, who are usually only distinguishable by the degree of cruelty with which they treat the protagonist.

Writing well about yourself is very difficult. “It isn’t easy to say your life broke down,” wrote Charles D’Ambrosio, in his book of collected essays, Loitering. “Nothing is quite so false, in writing, as the heartfelt confession.” Neither the True Story nor the True Confessions of today are great literature. But that’s not really the point. One story from the February issue is essentially just two widowed people falling in love in a continuing ed creative writing class. The True Story heroines of today are much crankier than the ones MacFadden was selling—happy endings usually involve men going to great lengths to prove they’re not awful, as if they’re being punished for the magazines that came before them. “Mr. Wonderful and his brethren could find someone else who’d just fallen off the turnip truck—that sucker wasn’t me, ” says one young woman, after a man says, “Hi,” to her.

In “Spring Job Fair” from the March 2017 issue of True Confessions, the heroine is about to finish college and works nights as a waitress at a truck stop. During an interview for an unspecified office job, the interviewer begins to hit on her. In most of the MacFadden confessionals, this would be the start of a great romance; the day she met The Man Who Rescued Her From The Truck Stop. But instead. she leaves feeling anxious, she thinks he’s a creep. And that’s all. She graduates, gets another job, and does not date that guy. It’s an entirely unremarkable story, but it feels like a victory.

[A note on sourcing: When possible, I identify stories by their specific issue and year. Many of them were included in a compilation put out by MacFadden Publishing in 1979, True Confessions 1919-1979: Sixty Years of Sin, Suffering, and Sorrow, in which case stories are identified by decade but not year. Images via True Renditions LLC]