I've Been Busy Thinkin' About Elgar

Who would be in my own personal “Boys” video and what would they be doing?

Myentire last week was derailed by Charli XCX’s new music video for her song “Boys.” The “Boys” video is fun about a few different levels because you can ask yourself:

- Which boy do I self-identify as?

- Which boy is my idealized self?

- Who would be in my own personal “Boys” video and what would they be doing?

Approximately three and a half questions. Nice. Amidst the brainstorming of my own “Boys” video (Steven Yeun eating an iced donut, Peter Capaldi buttoning up a cardigan, etc.), I was vaguely reminded of my high school crush who definitely would have been one of my “Boys” Boys if this were a decade ago, who at one point in time played Edward Elgar’s Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E Minor, a piece of music I’ll think of as romantic for the rest of my life. This happens to everyone, I know. Not the falling in love with a cellist when you’re 17, but the association of something not particularly romantic with someone particularly romantic, and then it’s stuck that way until you die.

First and foremost, who was my crush? Just kidding. Fuck. I meant to write: who is Edward Elgar? Elgar was an English Romantic-era composer who lived from 1857 until 1934. If you know him, it’s possible you know him for his most famous works, the Pomp & Circumstance Marches. Yes, thosemarches. The graduation one, among others. The other week I heard it played out of context of a graduation and thought to myself, “hm, does Pomp & Circumstance actually… kind of bang?” To be determined.

My introduction to Elgar was, in fact, high school, and it was from the myriad rehearsals I sat through listening to my crush play the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E Minor during which I played timpani. Playing timpani was often arduous albeit wonderful, because it’s an instrument that requires a lot of listening to everything around you. In the early days of learning a timpani part, you’ll count measures meticulously while you have extended rests; as you inch closer to a concert it feels more instinctive. You learn everyone’s cues. When there’s a soloist in a concerto, that experience, for me, was always heightened. Not only was I in touch with the body of the orchestra itself, but also one main person. Okay, and I was 17.

The Adagio — Moderato begins with a heavy chord. You can hear in the recording (Daniel Barenboim with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1974) as the bow hits the cello’s strings. Its opening refrain is heavy and intense, full of turmoil. It’s instantly tragic and therefore romantic as well. The woodwinds don’t enter until about 30 seconds in, a desperate whisper of the cello’s initial melody. From there, this first movement hesitantly inches towards its central melody around the 1:12 mark. It’s relatively simple in nature, but when echoed by the cello, there’s such an immense emotional depth to it barely matched by a full violin section. This is one of my favorite opening movements of any piece of all time. Can you see how a high school senior would lie on the floor of her bedroom and try to embed this piece into her nervous system? No? Well, that’s fine. I was a little weirdo. That’s not to say, however, the movement only consists of teenage angst. There’s a bit of lightness around the 3:44 mark that drifts in with a particular coolness.

Its second movement, the Lento — Allegro molto begins not dissimilarly in its opening phrase but quickly builds to a false start. The solo that begins this movement feels much more abstract. Elgar, despite my wildest dreams, was not writing his concerto as a grand romantic gesture. This was his last notable piece of music, composer in 1919 following the end of the First World War. While Elgar was perhaps considered a Romantic-era composer, there is a strictly Modernist feel to a movement like this. Noticeably disorienting, however beautiful it remains, grappling with itself and the world in which it lives. There’s almost a frantic nature to the cello here, a scrambling to say something, anything.

Now, the Adagio, to me, regardless of the context in which Elgar wrote the piece, is absolute pinnacle of romance. As a piece of music, there’s such a fullness to it. It’s simultaneously wistful and joyful; nostalgic and new. I have always loved the sound of the cello and the texture it provides within an orchestra, but this is the piece of music I think of when I think of the cello. It defines it. When I revisited Elgar’s concerto recently, this was the movement in which I got up to turn off my air conditioning and restarted the track to get every inch out of it. Does it not just encapsulate how it felt to be 17? I don’t mean that in a condescending way either. I mean it in the way where every feeling seems like it is the most important and only feeling you’ve ever felt. An earnest drama.

Its fourth and final movement, the Allegro — Moderato — Allegro ma non troppo grasps for a similar tonality to its second, more disconcerting movement. It’s also the longest movement within the concerto, and like any fitting finale, covers a wider range of emotions. For example, I love the formal cheeriness at the 1:30 and the melody that follows. Whereas past movements of this concerto have felt more demure, subtle, aching, this is the one that goes really big. It’s unafraid now to be loud and wholeheartedly complex. Admittedly, there are times I lose myself in this movement — it darts all around, and if I’m not keeping it, it’ll leave me by the side of the road.

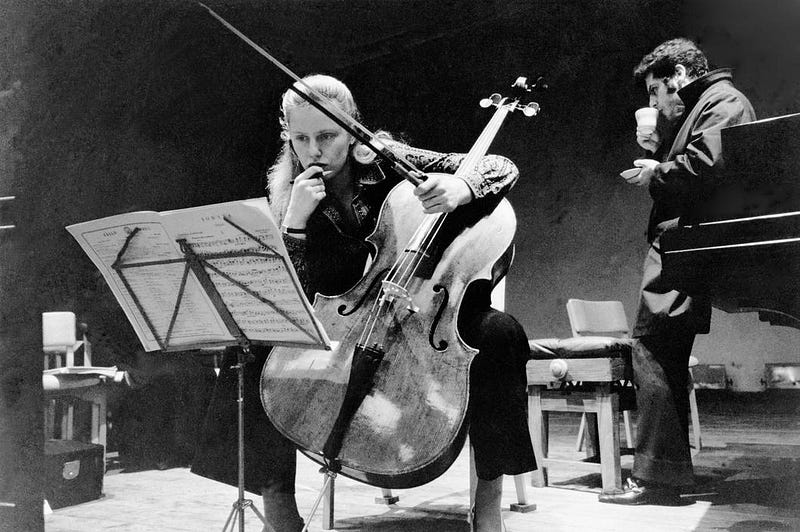

This movement also fully cements the entire concerto as one of the hallmark pieces for the cello. It’s undeniably incredible in every sense, and soloist Jacqueline du Pré puts such weight in it. Like the opening notes of the first movement, you can hear the smack of her bow on the strings. The power. One of the reasons I love this recording of it is because the conductor, Barenboim, was her husband.

Though this piece was not intended to be romantic, the performance is inherently so. It’s a collaborative action, a dance, a partnership. Though my reality of a high school crush fizzled out, lost touch, grew up, changed, unfriended in one of several needless Facebook purges, this recording can bring it all back once again.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.